Policy-based DNS in Windows Server 2016

High Resolution

GeoDNS providers help manage external access to an application as a function of the requesting client's location. Using these services, you can define which IP address is returned in response to a DNS request or whether the request is answered at all, making it easy to roll out and manage access to your application: You only need to publish a name, and the client automatically connects to the best available data center site. However, the internal publication of applications in distributed Windows infrastructures forces administrators to resort to workarounds when assigning IP addresses to a DNS request.

This lack of flexibility is compensated for either by the application itself controlling client access as a function of the Active Directory (AD) location (e.g., Exchange) or by administrators publishing the application on various locations under different names and passing these names to the right clients. For clients that permanently remain in one location, this workaround usually works quite well, but with frequent relocations, things often go wrong. Additionally, web services make it difficult to manage multiple names, for example, because SSL certificates must be issued in different names and if wildcard certificates are not available.

Policy-Based DNS

Windows Server 2016 gives you a tool – policy-based DNS – that lets you provide DNS resolution with the utmost flexibility. The possible applications of policy-based name resolution go far beyond geographically based load balancing and also help you increase the security of your entire IT landscape.

Consider a practical example: A company (call it "Contoso," in the typical Microsoft way) with offices in Germany, Japan, and Canada has decided to introduce an internal web-based collaboration platform. The client farm is made up of corporate and private devices, including smartphones and tablets, because employees love to make use of the bring-your-own-device policy. Centralized management of devices using Group Policy is therefore impossible, and you cannot issue trusted internal certificates. To tackle these challenges, you use the name of the public company's website http://www.contoso.com for the internal collaboration platform. A high-quality SSL certificate by a large provider, which all devices trust, already exists. However, this is also the namespace of the company's AD domain. DNS is provided exclusively on domain controllers (DCs), and you want to keep it this way, if possible.

The original plan to operate the entire platform at the Canadian data center had to be revised in the pilot phase because the latency of the WAN links to the other locations affected usability. This results in the following requirements:

- The German web server farm (10.0.101.99) must be reached from all productive network segments of the German site under http://www.contoso.com.

- The same applies for the Canadian (10.0.102.99) and Japanese (10.0.103.99) locations.

- From the guest networks, http://www.contoso.com must resolve to the public IP address 40.84.199.233.

This challenge can be solved with policy-based DNS in just a few steps, but to do so, you need PowerShell with DNS and AD modules (e.g., on a DC), which needs to be launched with increased rights. First, define the default entry for http://www.contoso.com:

> Add-DnsServerResourceRecordA -Name "www" -ZoneName "contoso.com" -IPv4Address "40.84.199.233"

Now place the client subnets on all domain controllers (Listing 1).

Listing 1: Placing Client Subnets on DCs

> $dcs = (Get-ADDomainController -Filter *).Name

> foreach ($dc in $dcs) {

Add-DnsServerClientSubnet -Name "DE-Prod" -IPv4Subnet "10.0.101.0/24" -ComputerName $dc

Add-DnsServerClientSubnet -Name "CA-Prod" -IPv4Subnet "10.0.102.0/24" -ComputerName $dc

Add-DnsServerClientSubnet -Name "JP-Prod" -IPv4Subnet "10.0.103.0/24" -ComputerName $dc

}

Depending on which client subnet the request comes from, the DNS server must give different answers. For this purpose, a so-called "zone scope" is necessary in the DNS zone contoso.com for each site:

> Add-DnsServerZoneScope -ZoneName "contoso.com" -Name "DE" > Add-DnsServerZoneScope -ZoneName "contoso.com" -Name "CA" > Add-DnsServerZoneScope -ZoneName "contoso.com" -Name "JP"

Now, add an A record for http://www.contoso.com with the respective IP address to each zone scope (Listing 2). To establish the location dependency, you will be defining three DNS policies that must be rolled out individually on each server (Listing 3).

Listing 2: Adding Records to Zone Scopes

> Add-DnsServerResourceRecordA -Name "www" -ZoneName "contoso.com" -ZoneScope "DE" -IPv4Address "10.0.101.99" > Add-DnsServerResourceRecordA -Name "www" -ZoneName "contoso.com" -ZoneScope "CA" -IPv4Address "10.0.102.99" > Add-DnsServerResourceRecordA -Name "www" -ZoneName "contoso.com" -ZoneScope "JP" -IPv4Address "10.0.103.99"

Listing 3: Defining DNS Policies

> $dcs = (Get-ADDomainController-Filter *).Name

> foreach ($dc in $dcs) {

Add-DnsServerQueryResolutionPolicy -Name "Client Subnet DE" -ClientSubnet "EQ,DE-Prod" -ZoneName "contoso.com" -ZoneScope "DE,1" -Action ALLOW -ComputerName $dc

Add-DnsServerQueryResolutionPolicy -Name "Client Subnet CA" -ClientSubnet "EQ,CA-Prod" -ZoneName "contoso.com" -ZoneScope "CA,1" -Action ALLOW -ComputerName $dc

Add-DnsServerQueryResolutionPolicy -Name "Client Subnet JP" -ClientSubnet "EQ,JP-Prod" -ZoneName "contoso.com" -ZoneScope "JP,1" -Action ALLOW -ComputerName $dc

}

From now on, the response from the respective zone scope is returned for requests from the individual production client subnets, even if a DNS server from the "wrong" location is requested. Clients from all other subnets (thus, also those on guest networks) receive a response from the default scope.

System Internal Processes

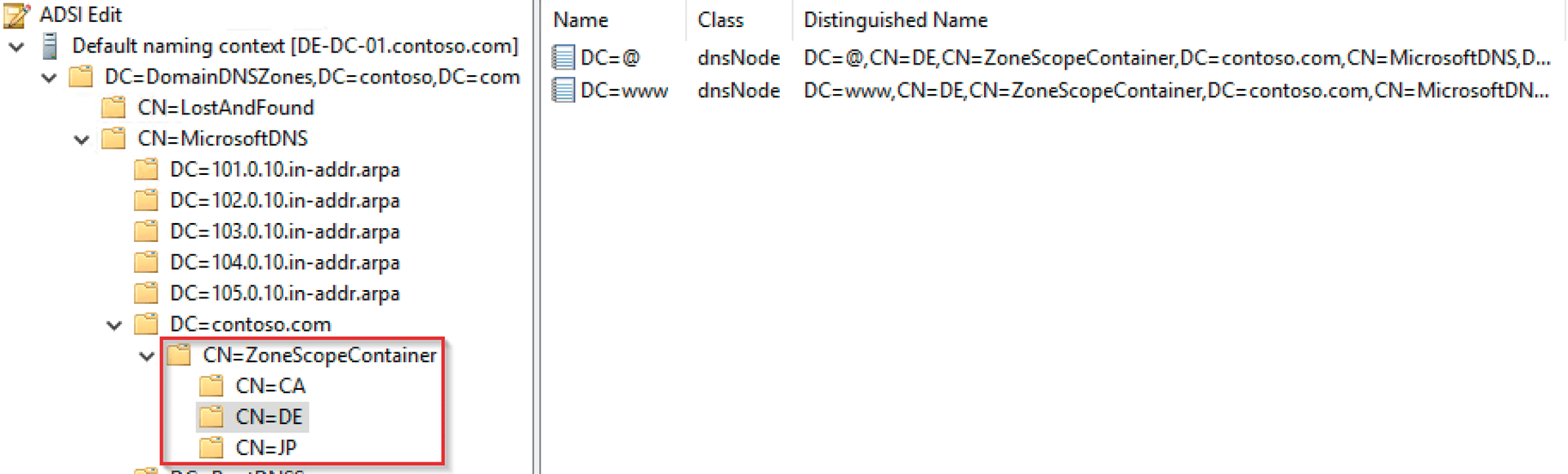

If you were now to take a look at the DNS management console, you would probably not find any trace of the recently executed action. Indeed, client subnets, zone scopes, and DNS policies can be managed exclusively in PowerShell. To see where the zone scopes with their respective entries are stored, use AdsiEdit.msc to connect to the name context,

DC=DomainDNSZones,DC=contoso,DC=com

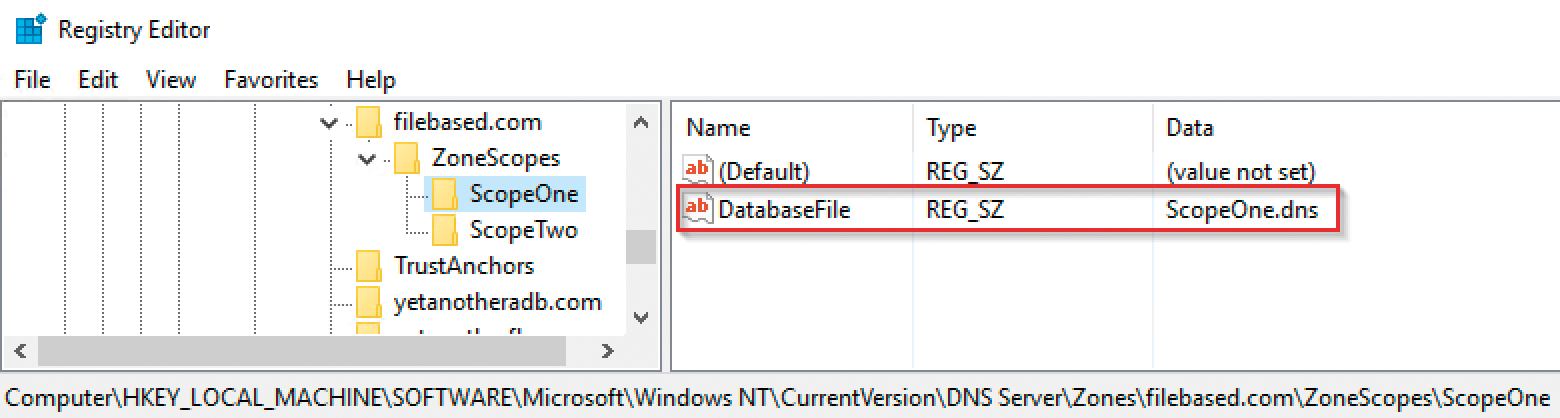

as shown in Figure 1. However, even a file-based DNS zone can include zone scopes. The scope data is here, along with the zone, with the same name as the subdirectory: C:\Windows\System32\DNS\ (Figure 2).

C:\Windows\System32\.The files have the default DNS format and both the zone scope container in AD and the subdirectory in the DNS folder will only be created if a zone scope is created for the zone. However, the zone scopes of a file-based DNS zone will not be transmitted, even between two Windows Server 2016 machines. If you really want to assign zone scopes to file-based zones, you need to manage the zone scopes and their respective records separately on each server or transfer the scope files from the master server by some other means. In each case, however, you need to create the zone scope for each server; otherwise, the files are not found (Figure 3).

The client subnets and DNS policies are only ever stored by the server and in the registry branch HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\DNS Server\. The names of keys and values and the content of the registry entries are available here and therefore allow inventory, documentation, and diagnostics using tried and trusted tools if no tools geared specifically to policy-based DNS are available.

How DNS Policies Work

The operating principles of DNS policies are more like firewall rules than Group Policy. For one thing, only the first policy for which all conditions apply actually works. For another, the DNS policies do not configure any settings; they only decide whether the DNS server responds to the request (ALLOW), ignores it (IGNORE), or refuses a response (DENY). The response returned in the above example for the IPv4 address to the request for http://www.contoso.com is included in the DNS configuration. Therefore, the DNS policies for each standards-compliant DNS client are completely transparent.

To plan and implement your DNS policies optimally, you need to know these simple rules, which the policies follow:

- When a DNS request is received, the policies at server level are first checked in the order in which they were defined (

-ProcessingOrder). If all the conditions of a policy apply, it is used, and processing is complete. Because at this moment it is not yet ensured that the server actually hosts the requested zone, server-level policies can only haveDENYorIGNOREas a result. - If none of the server-level policies apply, the requested DNS zone comes into play. If the server is authoritative for this zone, the zone-level policies are checked and executed if the conditions are met. If the server is not authoritative, it will answer the request.

- Conditions within a policy are ANDed by default. In other words,

-ClientSubnet 'EQ,JP-Guest' -QueryType 'NE,SRV'

will apply to all requests that come from the JP-Guest subnet and are not of the SRV type. If you want to change this behavior, and OR the criteria of different types, use the -Condition parameter, which accepts the values AND (default) and OR.

- Each condition has to include one or both of the

EQ,value1,value2,… orNE,value1,value2,… expressions. The possible values in theEQclause are ANDed (condition applies if none of theNEvalues fit). Whereas, values within theNEclause are ANDed (condition applies if none of theNEvalues fit). - Multiple policies on the same level (i.e., server level or in the same zone) need to have different rank numbers (processing order). If you add a new policy and specify an assigned rank number, your new policy receives the requested processing order, and existing policies in the ranking move down a slot.

You can use the following types of criteria to control the behavior of your DNS server: client subnet, transport protocol (TCP or UDP), Internet protocol (IPv4 or IPv6), IP address of the DNS server (if it listens on multiple interfaces), fully qualified domain name (FQDN) of the request (wildcards are allowed at the beginning, e.g., *.contoso.com), type of request (A, TXT, SRV, MX, etc.), and the time in the local time zone of the DNS server. The individual criteria are described in detail on TechNet [1].

Policies for Recursion

As we have already seen, the DNS policies only affect the server on which they are defined. However, in an internal Windows network, it is often the case that a DNS server can only respond to a small number of queries that are addressed to it. Instead, it forwards them to other servers, which are defined as forwarders for the respective zone or globally.

To control this behavior for a DNS server based on Windows Server 2016, you use policies. You can configure a DNS server so that it does not respond to requests for addresses from the facebook.com zone on production networks like this:

> Add-DnsServerQueryResolutionPolicy "Deny FB to production" -Action DENY -ApplyOnRecursion -Fqdn "EQ,*.facebook.com" -ClientSubnet "EQ,DE-Prod,CA-Prod,JP-Prod"

If you want to establish a sort of honeypot process and forward requests that meet specific criteria to an alternative DNS server, you can use recursion scopes, which are handled like zone scopes and include three parameters: the name of the zone for which the recursion applies, a list of forwarding IPs, and the parameter -EnableRecursion, which determines whether recursion is allowed in this recursion scope.

The recursion scopes are also stored in the registry (HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\DNS\Parameters\ServerScopes) in a different branch from the zone scopes and the policies.

Zone Transfer Policies

Although it generally occurs less frequently than answering or forwarding name resolution requests, a Windows DNS sometimes has to transfer a request for a zone transfer. This type of interaction with other systems can also be controlled by policies and follows the exact same logic as name resolution policies.

You can define a zone transfer policy at the server or zone level and make it dependent on a wide variety of criteria, with one difference: You cannot use zone scopes to provide different versions of zones in the event of the zone transfer. The default scope is always transferred, provided the zone transfer is generally permitted by the policies.

Limited Manageability

At this point, the DNS policies can be managed exclusively by PowerShell, but if you are planning an extensive policy design in addition to client subnets, zone scopes, and recursion scopes, it can become confusing quickly.

A logical place for a DNS policies GUI would be in the IPAM features management console, which is based on Server Manager. One can only hope that Microsoft supplies a corresponding GUI. Unfortunately, a cmdlet for testing created policies is also missing – the community is likely to finish the development work faster than Microsoft in this case.

If you define and manage DNS policies with PowerShell, you must consider the following:

- No new cmdlets have been created in the area of policy-based DNS. To create new objects, be it zone scopes, recursion scopes, client subnets, or policies, you need

Add-Cmdlets. - The

-ComputerNameparameter only accepts one value for all cmdlets. If you want to create or change objects on multiple DNS servers (which is probably par for the course), you either need to use a loop (as in the earlier example) or resort toCIMSessions, with which you can transfer an entire array. - You can copy policy-based DNS objects from one server to another:

> Get-DNSServerClientSubnet -ComputerName SERVER1 | Add-DNSServerClientSubnet -ComputerName SERVER2

Note that all objects already have to exist on the destination server before you can refer to them. For example, if a policy has a subnet condition, all the client subnets included in the condition have to be created before creating the policy.

- When DNS zones are stored in the AD, the zone scopes are transferred by AD replication, which can take some time, especially between different AD sites. Until the zone scopes have been replicated on a domain controller, you cannot create any policies that relate to them on the DC.

Conclusions

Policy-based DNS is a powerful tool that gives you a superior approach to customizing name resolution under Windows Server 2016 to suit your organization's needs. Unfortunately, managing it is quite a confusing experience right now, which is preventing the rapid spread of this technology. If you already routinely automate IT processes with PowerShell, though, you can immediately benefit from policy-based DNS.