Detecting malware with Yara

Search Help

Yara is a useful open source tool for searching, finding, and acting on text strings or patterns of binary text within a file. The project website [1] calls Yara the "pattern-matching swiss army knife" for malware detection.

You can download Yara onto your Linux system using RPM, apt-get, or any other package manager. Windows users can download the executable from the Yara main web page. Source code is also available.

Yara, which received some attention for its role in finding and defeating a Trojan called BlackEnergy, may have had its 15 minutes of fame around 2013 or 2015. But malware attacks have been on the rise. Plus, a lot has been written over the past couple of years about the practice of "threat hunting," which is where a security professional proactively hunts for probable threats on the network. Threat hunting requires more than just reviewing logfiles or waiting for signature-based Intrusion Detection System (IDS) tools to send alerts. A threat hunter looks deeply into systems and system files. Yara is an important tool for this kind of proactive malware detection.

I've also seen security professionals use Yara during an actual attack. Once they've determined that a system has been compromised, they'll use Yara to quickly determine if the attack has spread to other systems.

How Does Yara Work?

Yara uses Python-based rule files to look for patterns in a file. The syntax for using Yara is as follows:

rule NameOfRule

{

strings:

$test_string1= "James"

$test_string2= {8C 9C B5 L0}

Conditions:

$test_string1 or $test_string2

}

In the preceding code, you start by naming the rule – you can use any name you wish. After the name, supply a bracket to start the function. You can then list strings you wish to find within the file. The $test_string1= "James" variable tells Yara to look for the actual text string James within the file. The test_string2= variable tells Yara to look for binary code, rather than a text string. The Conditions: section tells Yara what to match. In this case, Yara looks for either string.

Once you've defined the patterns, Yara can go out and look for problems.

A Very Simple Example

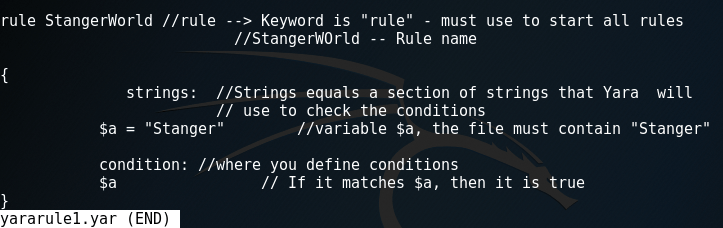

Figure 1 is a very simple example that tells Yara to search for the word Stanger. I've named the rule StangerWorld. If Yara finds a match, the word StangerWorld will appear whenever there is a match, along with an indicator of the file. The next section defines the strings to look for. In this case, I look for the text word, Stanger.

The condition section tells Yara what to do. In this case, the file tells Yara to report that it has found something.

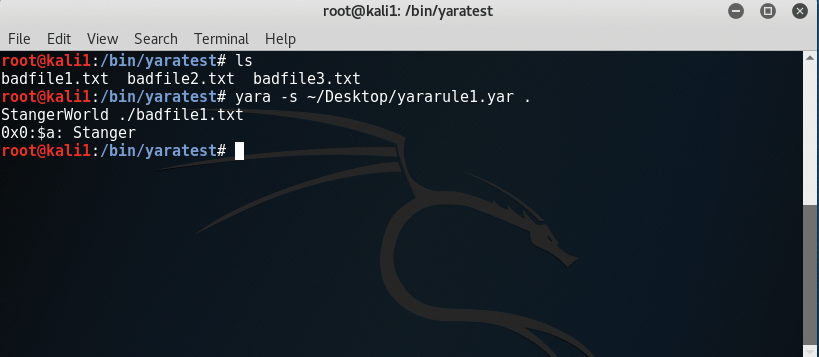

To test if Yara is working, I create three files named badfile1.txt, badfile2.txt, and badfile3.txt. I put random words in each of the files. I only put the word Stanger inside of one file.

I then tell Yara to read my ambitious little rule file and look inside every file within the current directory:

yara -s yararule1.yar .

In Figure 2, you see that I've run the preceding command.

Notice that Yara reported the contents of only one file: badfile1.txt. The report basically tells you that it found a match for variable $a, the word Stanger. This simple command demonstrates how to create a rule and issue a command against a file or set of files. More sophisticated examples will show you how Yara is used today by security professionals.

What to Look For

Yara can search for patterns inside of any file – either as text or in binary form. Suppose you suspect that someone has distributed text files that contain a suspect URL. You can configure Yara to automatically search for files that have that URL embedded within it.

Or, you can search for a binary file that has a hard-coded instruction in it. A friend of mine once told me how she detected an attack using Yara. She was asked to take a look at a few Industrial Control System (ICS) implementations at a power plant. She noticed a couple of things about a particular Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) console application. One of these console applications kept making Domain Name System (DNS) queries.

She found that this was a bit odd, because most SCADA systems don't use Internet-based DNS or Internet-based time systems. To help determine if the system had been compromised, she ran Yara with a rule file that contained the following:

Rule DNS

{

strings:

$test_string1= " (#cmd='whoami')"

$test_string2= " (#cmd='nslookup')"

$test_string3= {9D J5 G8 P9}

Conditions:

$test_string1 or $test_string2 or $test_string3

}

By searching for DNS-specific commands, such as whoami and nslookup, the ruleset was able to find that one of the SCADA system's files had been compromised.

Yara can also search for installed code (e.g., Apache Struts, a Linux kernel, or a Windows DLL) to identify suspicious code running inside of your (supposedly) secure daemons, services, and applications.

Information Sharing

One of the first things a good threat hunter does is look for specific information about the contents of malware files. A good starting place to find information on active malware is the ICS-CERT website [2]. Major OS vendors, such as Microsoft, Cisco, and Red Hat also provide detailed information about malware.

Once you have found information specific to a particular piece of malware, all you have to do is create useful rules to check sensitive files on key servers. It is possible, of course, to set up a crontab or script to automate this task.

Creating Rules for Yara

Yara may one day be integrated with artificial intelligence (AI) that will automatically determine what to search for, but we're not at the AI stage yet. You still need to create or obtain rules that tell Yara what to do. (See the box entitled "Obtaining Rules.") One thing that I do is use the strings command against files that I know have been compromised. I look for specific indicators of that compromise and then place those indicators into a Yara rule file. For example, suppose you have a PDF file that has a URL inside of it that leads to a phishing site. Listing 1 is a simple Yara rule that looks for files with a hidden HTTP link.

Listing 1: Hidden Link

01 rule phishing_pdf {

02

03 meta:

04 author = "James Stanger"

05 last_updated = "2017-09-12"

06 category = "phishing"

07 confidence = "high"

08 threat_type = "phishing exploit"

09 description = "A pdf file that contains a bad link"

10

11 strings:

12 $pdf_magic = {68 47 77 22}

13 $s_anchor_tag = "<a " ascii"

14 $s_uri = /\(http.+\)/ ascii"

15

16 condition:

17 $pdf_magic at 0 and (#s_anchor_tag == 1 or (#s_uri > 0 and #s_uri < 3))

18 }

You can also use Yara to monitor applications, rather than simply files. For example, using the strings command, I reviewed the contents of a database server with a compromised MySQL binary. A forensics professional informed me that the following strings belonged to a Trojan:

7A 50 15 00 40 00 67 30 15 02 11 9E 68 2B C2 99 6A 59 F7 F9 8D 30 PROTEANNDDGMTWHYNT

The expert had found this code using his knowledge of the MySQL source code – with a bit of help from an anti-virus application. Using Yara, I created the rule in Listing 2.

Listing 2: Searching MySQL

01 Rule MySQL_bad

02 {

03 strings:

04 $test_string1= "PROTEANNDDGMTWHYNT"

05 $test_string2= {7A 50 15 00 40 00 67 30 15 02 11}

06 $test_string3= {9E 68 2B C2 99 6A 59 F7 F9 8D 30}

07 Conditions:

08 $test_string1 or $test_string2 or $test_string3

09 }

In Listing 2, I tell Yara to look for the strings that my forensics friend has given me, and I tell it to give me a match if any of the three strings are found.

It's also possible to have Yara capture files or commands and then block the offending application from running, and even place it into a quarantine (Listing 3).

Listing 3: Quarantine

01 Rule Equifax_Malware {

02 meta:

03 description = "Suspicious malware for threat hunting"

04 Block = true

05 Quarantine = true

06 Log = true

07 CaptureCommandLine = true

08 LogSubprocesses = true

09

10 Strings:

11

12 // place anything in here you wish that is related to PowerShell

13

14 condition:

15 2 of ($hc)

16 }

Notice the log and quarantine rules in Listing 3. If Yara is run as root, it can actually grab a file and place it into a quarantine directory. In Listing 3, Yara will only do this if two conditions are met.

Applied example

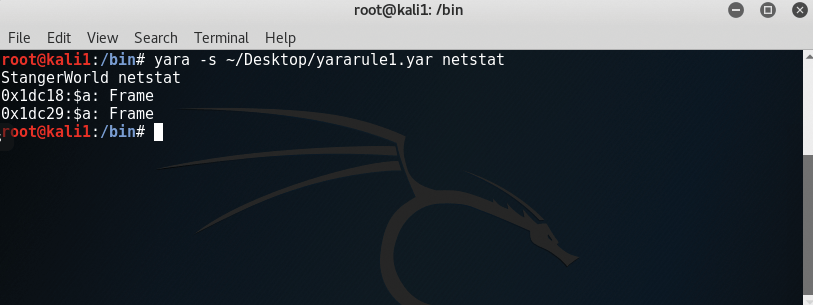

A few weeks ago, I was concerned that one of my client's Linux systems had become compromised. The system had been hit by malware that involved a Trojan that replaced the /bin/netstat command with a duplicate that had an illicit server installed. The suspect binary had several references to the word Frame in it.

I studied the code for the /bin/netstat command and noticed that, for my system, the netstat command only listed the word Frame twice. So, I created a simple rule and ran Yara. Figure 3 shows the result.

Notice that the word "Frame" in the figure is listed twice. This was a good things for me, because I had read the original open source code, where the word "Frame" is, in fact, listed twice. This was a very quick and dirty use of Yara, but it saved me a lot of time and lost sleep, because I now knew that my server probably hadn't been compromised in the same way as the one that belonged to my forensics buddy.

Finding Malware Families

You can also use Yara to identify families of malicious code. The folks who attack Whole Foods, Equifax, and Target aren't all that interested in creating fancy new code. They typically use variations of existing malware. Using Yara, you can fairly easily identify the type of code running, which might help you identify the attacker. If you know, for example, that a particular group (e.g., an Anonymous subgroup) tends to favor one type of malware, you can learn more about their tactics and identify common-sense next steps in your response.

For example, the rule in Listing 4 tells Yara to look for various commands within a file.

Listing 4: Looking for Commands

01 {

02 strings:

03 $a1 = "FONTCACHE.DAT" ascii

04 $a2 = "getpd" ascii

05 $a3 = "MCSF_Config" ascii

06 $a4 = "NTUSER.LOG" ascii

07 $a5 = "getp"ascii

08 $a6 = "unlplg" ascii

09 $a7 = "CSTR"ascii

10 $a8 = "ldplg" ascii

11 condition:

12 3 of them

13 }

In Listing 4, Yara will return a matched pattern if a file contains three of the strings. You could type in all of them if you wished Yara to report only if all the strings are present.

The order of the different variables doesn't matter. What does matter is that you specify certain strings that are in the piece of malware. For example, in the above example, Yara is looking for typical gets and lookups used with a family of malware called WESSPRESSO. WESSPRESSO was devised to attack WordPress applications that have a specific zero-day flaw.

As you can see in Listing 4, WESSPRESSO looks for Windows-specific calls, including the NTUSER log. The rules also tell Yara to look for the getp and unlplg commands, which are variants of WESSPRESSO.

It's also possible to create rules that look for specific strings running in code. For example, Listing 5 looks for driver commands within code that is running, as well as text strings.

Listing 5: Searching for Driver Commands

01 {

02 strings:

03 $a1 = {8F 6E 1B 68}

04 $a2 = {K0 3D 67 B2}

05 $a3 = {A5 63 4F F9}

06 $b1 = {9E 3Y 3C 78}

07 $b2 = {K0 4C 87 G5}

08 $b3 = {M3 L3 4Y LF}

09 $c1 = "IoAttachDeviceToDeviceStack" ascii

10 $c2 = {L0 $E 76 C3}

11 $c3 = "PsCreateSystemThread" ascii

12

13 condition:

14 all of ($a*) and 3 of ($b*, $c*)

15

16 }

In Listing 5, the condition statement basically tells Yara to match any of the codes in groups a, b, or c. It is relatively easy to change the contents of Listing 5 to review working binaries for any type of code you wish. All you have to do is look up certain code strings in the applications, services, and daemons that you're using. Then replace the existing code to match the code you're hoping to find.

Yara also gives you the option of using multiple rule files. See the box entitled "Using Multiple Files."

Conclusion

Over the years, I've heard many harrowing stories about how expensive it is to have professionals go in and conduct a postmortem on compromised files and servers. Yara is no substitute for a good cybersecurity professional, but with Yara, it's possible to take many of the steps a good threat hunter, forensics professional, or security analyst would make. I highly recommend it!

You'll eventually need to learn more sophisticated conditions than the ones shown in this article. But after you create a few of your own rules, you'll find that it's not very difficult to move your knowledge of Yara to the next level.