Build system images with Kiwi

Conjurer

System images are installed and preconfigured operating systems, including application software, for immediate use. They come in various forms. The best known is probably the virtual system, which is used in the platform as a service (PaaS) cloud. Other uses include preloading desktop systems and laptops or SD card images for single-board computers.

You can create system images step by step by installing and configuring a system according to your wishes or existing standards and then creating a copy of the installation. However, don't forget to remove some of the configuration files when you're done (e.g., those containing the characteristics of the source system, such as MAC addresses or the hard drive IDs). Of course, this procedure is relatively time consuming and prone to error. If you are looking for an easier way to build an image, try a tool like Kiwi.

Kiwi NG [1] builds different types of ready-to-use system images (appliances), such as those for starting a virtual machine or for installing on a bare metal system. In the latter case, the tool copies the configured system image directly to the local storage medium so that it is immediately ready for use the next time the hardware is booted.

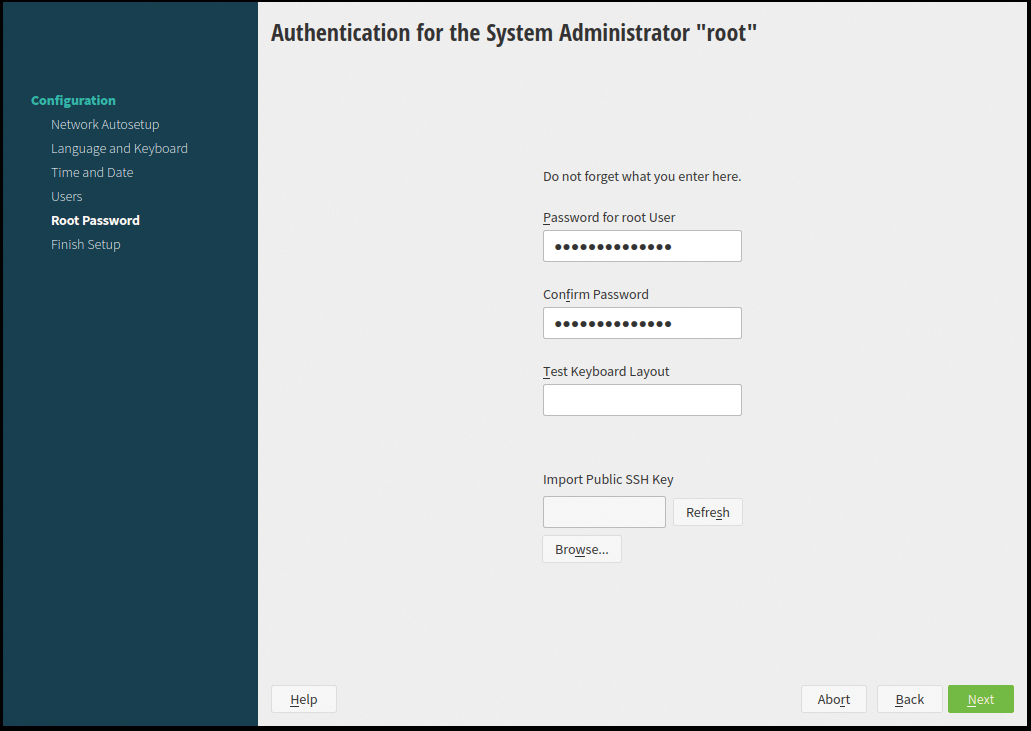

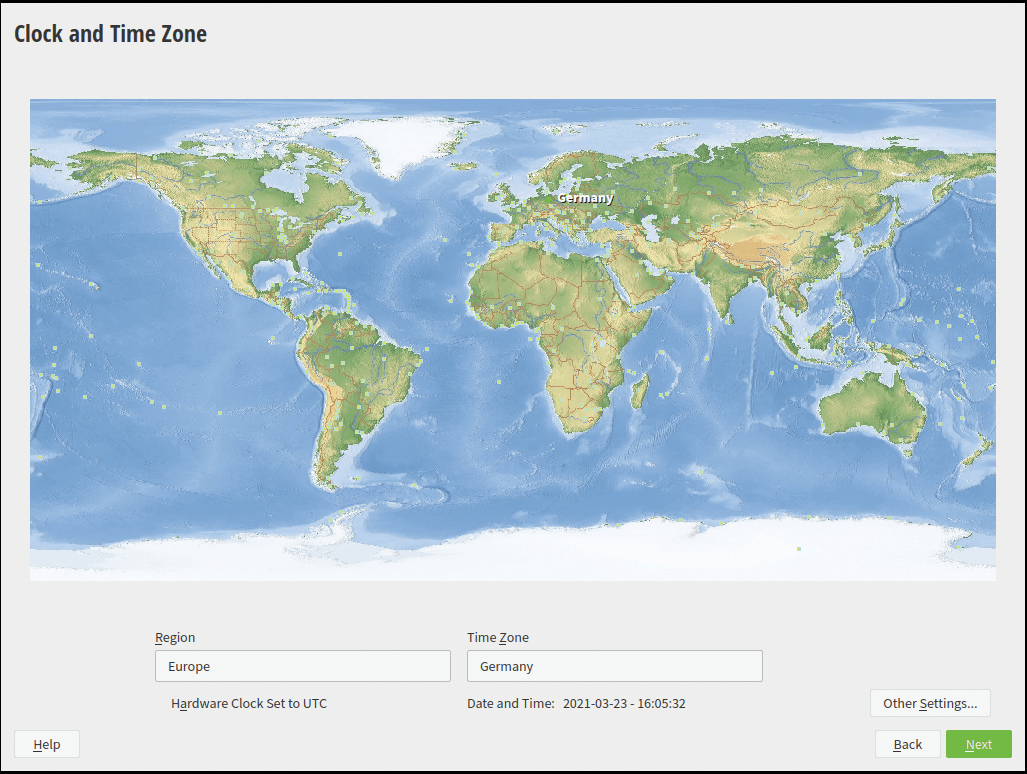

This type of installation can be extended to include configuration services, such as yast-firstboot on SUSE. This YaST module then queries user information such as name and password and even the time zone at first boot (Figure 1). Kiwi can do more than create images for SUSE: It works with all other RPM-based distributions, as well as for Debian/Ubuntu and Arch Linux. The installation of Kiwi itself is explained in the box "Setting Up Kiwi NG."

Using Kiwi

Regardless of the type of system image to be created, you need a description of the system in XML format that contains all the details of the future system (Listing 1), such as package lists and sources, users to be created with passwords and groups, and the partitioning or logical volume manager (LVM) layout.

Listing 1: Kiwi XML Profile

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<image schemaversion="6.8" name="Leap-15.2_example">

<preferences>

<version>1.15.2</version>

<packagemanager>zypper</packagemanager>

<locale>de_DE</locale>

<keytable>de</keytable>

<timezone>Europe/Berlin</timezone>

<rpm-excludedocs>true</rpm-excludedocs>

<rpm-check-signatures>false</rpm-check-signatures>

<bootsplash-theme>bgrt</bootsplash-theme>

<bootloader-theme>OpenSuse</bootloader-theme>

<type image="vmx"

filesystem="ext4"

bootloader="grub2"

kernelcmdline="splash"

firmware="efi">

</type>

</preferences>

<users>

<user password="$1$wYJUgpM5$RXMMeASDc035eX.NbYWFl0"

home="/root"

name="root"

groups="root"/>

</users>

<repository type="rpm-md" alias="Leap_15_2" imageinclude="true">

<source path="obs://OpenSuse:Leap:15.2/standard"/>

</repository>

<packages type="image">

<package name="checkmedia"/>

<package name="patterns-OpenSuse-base"/>

<!-- .... -->

<package name="openssh"/>

<package name="kernel-default"/>

</packages>

<packages type="bootstrap">

<package name="udev"/>

<package name="filesystem"/>

<package name="glibc-locale"/>

</packages>

</image>

After Installation

In most cases, it is not enough simply to install packages; you also need to adjust their configurations. The simplest approach for inserting your own files into the appliance is to create a directory named root/ and rebuild the structure of the intended filesystem there with the configuration file location.

For example, if you want an /etc/appliance_version file on the later system, it must be stored in root/etc/appliance_version with the desired content. Kiwi copies the content of this directory to the filesystem after installing the packages named in the XML profile, which also allows files from the installation packages to be overwritten and thus customized.

After copying the packages to the future system and setting them up, you still might need to configure services for automatic startup. For this, Kiwi offers the possibility of storing scripts that call the tool at defined points of the build process.

Roughly speaking, Kiwi's work can be divided into two main processes: preparation and creation. The preparation part includes the steps discussed so far (i.e., installing the packages, creating users and groups, copying the files from the root directory and any additional archives specified, and finally, calling the config.sh script if it is present).

Finally, a Script

Kiwi runs config.sh in a chroot environment on the future filesystem. The script can contain arbitrary program calls that further customize the system, including the previously mentioned task of enabling services at startup (i.e., systemctl enable <service>), as well as downsizing of the filesystem by removing unneeded files. The preparation part is now complete; Kiwi has installed the future appliance into a directory and customized it according to your specifications.

In the next step, Kiwi now creates one or more image types from this directory. Before this happens, you will want to check the configuration files in the future filesystem again. This step is very helpful when you are working on a new image, especially if many adjustments need to be made to the filesystem. If you have no need for this step, the preparation and building process can be processed directly in a call to Kiwi and the desired system image created directly.

An image of type OEM from the directory in which the necessary description files are located (the --description parameter) is created in the directory specified by --target-dir (e.g., /tmp/Kiwi-ng-builddir, in this case):

$ sudo kiwi-ng --type oem system build --description . --target-dir /tmp/Kiwi-ng-builddir

where the files of the finished image are subsequently located.

Editing Examples

Examples of image descriptions (i.e., XML profiles with scripts and a root directory) are provided by the Kiwi maintainers in a repository on GitHub [2]. Local cloning of the repository, including the examples in this article, offers a quick-start option. The examples can then be tried out directly.

From the examples provided by the maintainers, you can quickly create your own image with individual customizations for a virtual machine. To do this, clone the repository with git, change to the appropriate directory, and view the content of the example directory (Listing 2).

Listing 2: Cloning a Repository

$ git clone https://github.com/OSInside/Kiwi-descriptions $ cd Kiwi-descriptions/suse/x86_64/suse-leap-15.2 $ ls -1 config.sh config.xml root root/etc root/etc/udev root/etc/udev/rules.d root/etc/udev/rules.d/70-persistent-net.rules root/etc/motd root/etc/sysconfig root/etc/sysconfig/network root/etc/sysconfig/network/ifcfg-lan0

The config.xml file controls the build process by defining what should be installed and configured. After the build process, Kiwi copies the content of the root directory to the root filesystem. Finally, the config.sh script runs. In the example of Listing 3, the script enables the SSH daemon and chronyd and sets the systemd target to "graphical" (equivalent to the earlier runlevel 5).

Listing 3: config.sh

test -f /.kconfig && . /.kconfig test -f /.profile && . /.profile echo "Configure image: [$Kiwi_iname]..." suseSetupProduct suseInsertService sshd suseInsertService chronyd baseSetRunlevel 5

Often, time servers are useful (Figure 2) – either those belonging to the NTP pool project or your own. A few adjustments are all it takes. The chrony and chrony-pool-empty packages must be installed. Without specifying the latter, the system installs a package preconfigured for openSUSE time servers. The time servers to be used are listed in the root/etc/chrony.d/server.conf file:

server 0.de.pool.ntp.org server 1.de.pool.ntp.org server 2.de.pool.ntp.org server 3.de.pool.ntp.org

The entry suseInsertService chronyd in config.sh takes care of starting the chronyd service. Instead, the script can contain a systemctl call or any other commands. For some standard processes, Kiwi provides prepared functions for further simplification, as in the suseInsertService example. A list with explanations [3] of these functions can be found on the project's website.

An entry in the root/etc/motd file, such as:

Welcome to a modified openSUSE Leap 15.2 appliance.

gives you a "message of the day."

Final Configuration

If you want the user to set up the finished appliance on the first boot, openSUSE provides the yast2-firstboot package for this purpose [4]. If it is installed, the system asks the user for the individual configuration at the time of first boot, which includes the username and password, hostname, network configuration, time zone, and more.

The modules to be called are in the root/etc/YaST2/firstboot.xml file on the later filesystem. Listing 4 shows a sample configuration that starts the modules for the system language, keyboard layout, time zone, and a user to be created. The root password is also prompted for and set here, creating a customized image from a role model that can be installed and used immediately.

Listing 4: Querying System Configuration

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<productDefines xmlns="http://www.suse.com/1.0/yast2ns"

xmlns:config="http://www.suse.com/1.0/configns">

<textdomain>firstboot</textdomain>

<globals>

<enable_autologin config:type="boolean">false</enable_autologin>

</globals>

<workflows config:type="list">

<workflow>

<stage>firstboot</stage>

<label>Configuration</label>

<mode>installation</mode>

<modules config:type="list">

<module>

<label>Language and Keyboard</label>

<enabled config:type="boolean">true</enabled>

<name>firstboot_language_keyboard</name>

</module>

<module>

<label>Time and Date</label>

<enabled config:type="boolean">true</enabled>

<name>firstboot_timezone</name>

</module>

<module>

<label>Users</label>

<enabled config:type="boolean">true</enabled>

<name>firstboot_user</name>

</module>

<module>

<label>Root Password</label>

<enabled config:type="boolean">true</enabled>

<name>firstboot_root</name>

</module>

</modules>

</workflow>

</workflows>

</productDefines>