IT automation with SaltStack

Always on Command

In 2013, we were faced with a move to a new data center, combined with a change in infrastructure – away from classic bare-metal servers to well-dimensioned virtual machines (VMs). Until then, Puppet was used for configuration management, which brought with it many architecture-related problems and shortcomings. On the other hand, not all Puppet manifests could be immediately replaced, which is why the only solution was one that could be used in parallel.

After some comparisons, the decision was made to go with SaltStack, which even then came with its own Puppet module, allowing us to control Puppet from within SaltStack. Additionally, SaltStack (Salt for short) impressed with its modular architecture and high speed. Where Ansible and Chef's runtime was often unpredictable, SaltStack reliably delivered results after just a few seconds – regardless of whether it served 10 or 100 hosts. For example, load testing of the then-new platform was done with 300 Amazon Web Services (AWS) VMs rolled out by Salt Cloud in a matter of minutes.

SaltStack can be run in many ways: from the classic server-client architecture – master-minion in Salt parlance – to a serverless mode (masterless). SaltStack also demonstrates flexibility when it comes to the question of connectivity. It supports ZeroMQ, SSH, or a plain vanilla TCP mode (e.g., TLS). Proxy modules can also be used to connect systems that do not support SSH or Python. The proxy module then translates the Salt syntax into commands compatible for the target system.

SaltStack enables this versatility by using a modular design from the start. Whether it is a matter of describing desired states, establishing connections, performing actions, or displaying outputs: Everything is modular, interchangeable, and expandable. Many useful default settings are configured, and the admin can simply get started without any serious configuration overhead.

Many an admin never gets to see the depths of the modular building block. If demand increases and you are looking for time-based schedulers or REST APIs, you will find them all in SaltStack's scope of delivery. Whereas other automators have to rely on third-party solutions (or build around other tools), the Salt documentation succinctly explains how these tasks can be solved with just a few lines. The advantage is that the same terminology is always used and configurations are made in a familiar format – simply as another feature from the construction kit you combine and apply.

Setup

The usual SaltStack installation [1] comprises the master-minion-ZeroMQ variant. A Salt master is the instance that controls everything, sending the commands and receiving the results. It distributes the state and execution modules and other files to the minions with a built-in file server (saltfs). The Salt minion acts as a client and receives instructions from the master that are processed by executing state and execution modules and delivering information and results to the master.

More complex setups involve multiple master servers running in different zones, each controlling their own minions. These zone masters can in turn be controlled by a higher level master. However, describing such a configuration is beyond the scope of this article.

Assume an instance on a private network that runs a Salt master process. This instance has the hostname salt, which can be resolved by DNS. Two more instances are named minion01 and minion02. A Salt minion is already installed and running on them, and no configurations differ from the default.

When a minion starts, the first thing it does is look for its master. If the configuration does not specify otherwise, then the minion performs a DNS lookup for the name salt and attempts to connect to port 4505 (publisher port) of the address it finds. An unregistered minion then sends its public key to the master and asks to be registered. On the Salt master, you can list these keys and then check that both minions can be reached:

# salt-key list

Accepted Keys:

Denied Keys:

Unaccepted Keys:

minion01

minion02

Rejected Keys:

# salt 'minion0*' test.ping

With the command

salt-key --accept minion0*

the master accepts the minion01 and minion02 public keys, which are under its control from this point on. If everything goes well, the output acknowledges the minion name with True (i.e., the minion can be reached and controlled).

Targeting

To trigger an action on a minion, you need to know how to filter and address a specific instance from the minion list. In the default setup, this does not require static or dynamic host lists: The Salt master knows which minions are registered with it, and you can always build complex queries to address them. For example, to see the logrotate configuration file of all Debian hosts with two x86_64 CPUs and 4GB of RAM named minion plus two numbers at the end, you run the command:

# salt -C "G@os:Debian

and G@num_cpus:2

and G@cpuarch:x86_64

and G@mem_total:4096

and E@minion\d{2,}"

logrotate.show_conf

The information provided by the minions is referred to as grains in Salt-speak, and they appear with the prefix G@. Grains provide details about network interfaces, RAM, CPUs, the virtualization used, or other similar information. In the example, the master filters the grains by the keys os, num_cpus, cpuarch, and mem_total. Additionally, the minion\d{2,} regular expression introduced by E@ finds all hosts matching the desired naming scheme (i.e. minion01, minion02, etc.). The show_conf command from the logrotate module is then executed on these hosts.

If you regularly use such target filters, you can also store them in a YAML structure and reuse them as a nodegroup, which you call with:

# salt -C "N@group1" logrotate.show_conf

Nodegroups are even allowed to reference each other.

For example, nodegroup.conf could reference group2 and extend group1 with the condition that the init system must be systemd. In turn, the group3 node group could reference group2 and add a query that only finds hosts on the 10.10.10.0/24 network. Further possibilities and a detailed explanation of the syntax can be found in the Salt documentation; just look for the key word Targeting [2].

States

Salt typically uses state descriptions (states) to install packages or change configurations. States provide the description of a desired state, which can be an installed package or a file that must exist with certain content and defined permissions on the target system.

These states transparently call the appropriate execution modules (e.g., the aforementioned logrotate module) in the background, which then do the actual work. States are usually defined in YAML format, but they can also be designed variably and dynamically with the Jinja2 template engine. SaltStack also accepts other formats for state descriptions, including JSON, Python, or its own domain-specific language (DSL), PyDSL [3].

A shebang-style line can be used to override the default renderer dynamically, and you can even form renderer chains. The shebang

#! gpg | jinja | yaml

tells SaltStack to render the state first with GNU Privacy Guard (GPG), then with Jinja2, and finally as YAML. The GPG renderer searches the GPG keyring for the private key to match the public key used here; it encrypts and decrypts the string in memory. After that, the Jinja2 and finally the YAML renderer process the document. Basically, the default shebang is #! jinja | yaml.

For a state that installs the iotop package, save the content

Ensure that the iotop package is installed:

pkg.installed:

- name: iotop

in the /srv/salt/demo_state.sls file. The command

# salt 'minion01' state.apply demo_state

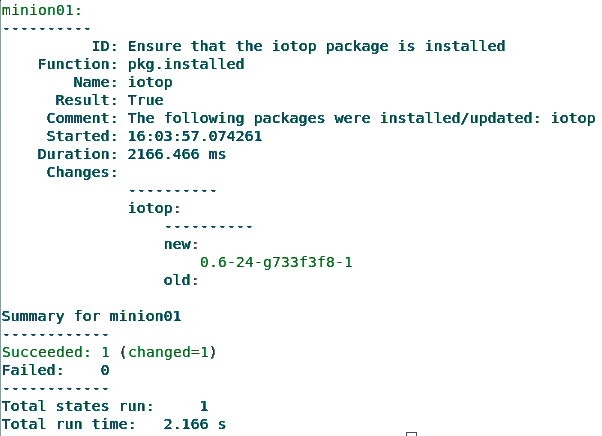

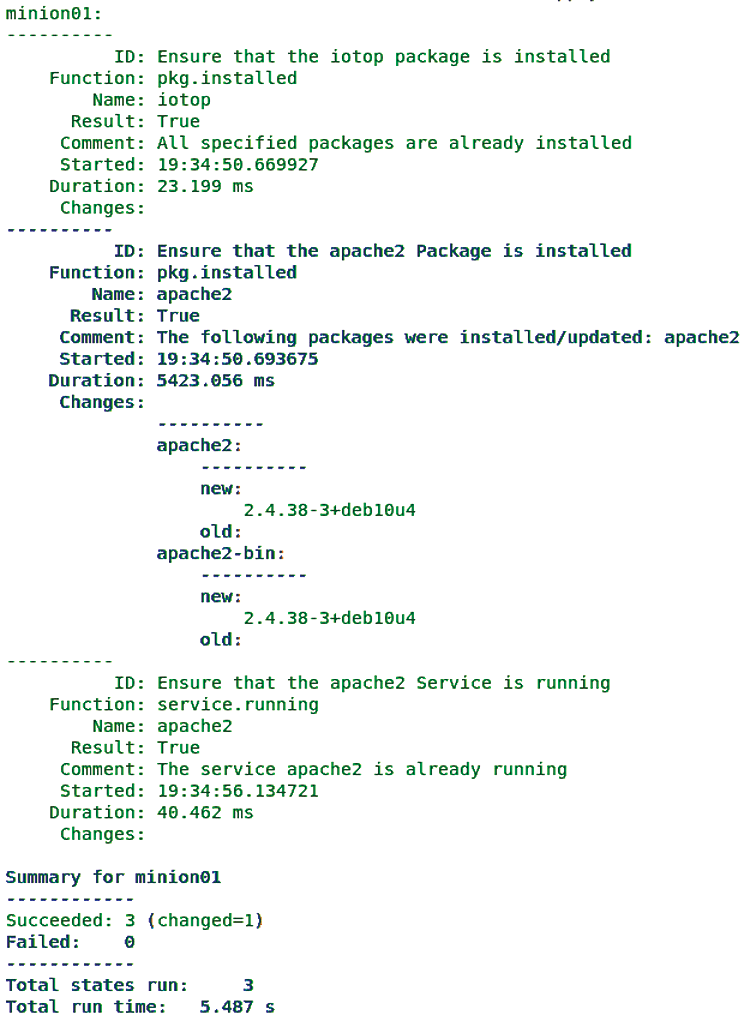

tells Salt to establish the appropriate state on minion01 [4]. The output will look like Figure 1. To get an output format that can be fed to a shell or Python script, add --out json to the command.

state.apply call to install a software package.Usually you will want to apply a whole set of states to one or more hosts. Instead of calling state.apply several times (which is possible), it makes more sense to create a file named /srv/salt/top.sls with the content

base:

'minion01':

- demo_state

that defines an environment (base), a target (minion01), and a list of states to be applied (demo_state).

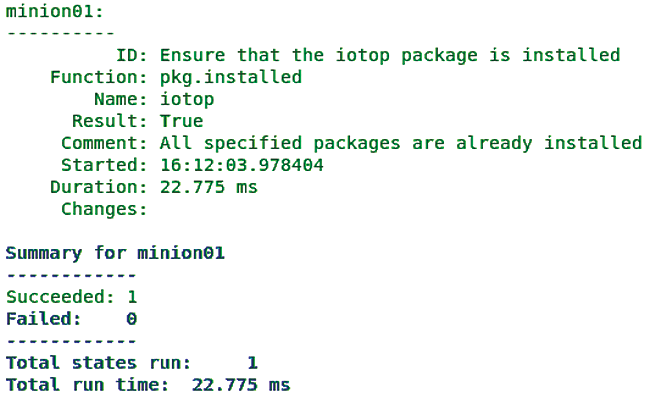

In the Salt world, the whole thing is then abstractly known as a highstate that can again be rolled out with state.apply, but without specifying explicit states. The output (Figure 2) is similar to that of the previous command, but with minor changes: The runtime of the highstate is far shorter, the Changes section is blank, and the Comment tells you that the iotop package is already installed.

Data Structures

In addition to grains that the minions send to the master, pillars are the data that the master sends to specific minions. These data structures can be used to define variables for templates, to store GPG-encrypted secrets, or to define simple mappings that abstract operating system-dependent differences.

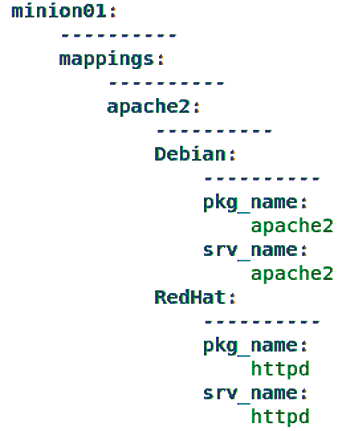

The first step is to create the /srv/pillar/mappings.sls file with the content:

mappings:

apache2:

Debian:

pkg_name: apache2

srv_name: apache2

Red Hat:

pkg_name: httpd

srv_name: httpd

Now you need to assign the pillar data to specific minions by creating a top file in /srv/pillar/top.sls with the content:

base:

'*':

- mappings

The following commands then update the pillars, and the pillar data is retrieved from minion01:

# salt 'minion01' saltutil.pillar refresh # salt "minion01" pillar.items

As a result, you now see all pillar data associated with minion01 (Figure 3).

minion01.If needed, you can also retrieve only subsets of the pillar data. To retrieve only the data for the mappings:apache2:Debian namespace, use:

# salt "minion01" pillar.get "mappings:apache2:Debian"

minion 01:

----------

pkg_name:

apache2

srv_name:

apache2

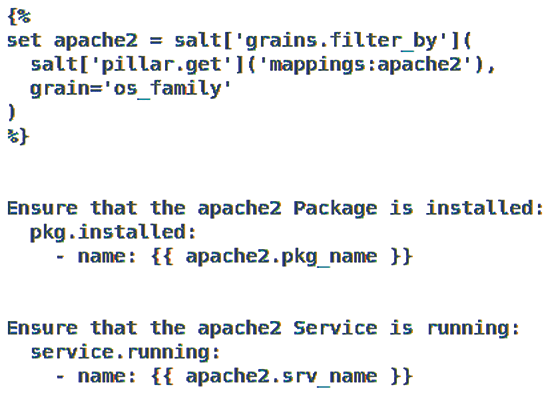

This command now allows reconciliation of differences in package names for Apache2 on Debian- and Red Hat-based distributions. Another state file in /srv/salt/apache2.sls (Figure 4) is used for this purpose.

Now add the following lines to the file /srv/salt/top.sls:

base:

'minion1':

- demo state

- apache2

A state.apply command returns the information in Figure 5, which shows that the iotop package is set up, some Apache2 packages have been installed, and the Apache2 service is already running.

state.apply command.Because of the mapping in the pillar data, the pkg.installed and service.running calls were automatically given the correct names. In other words, the same description works under both Debian derivatives and Red Hat offshoots.

A Look into the Future

In October 2020, VMware acquired SaltStack, whose future now seems more secure than ever. VMware said it wanted to expand its automation capabilities and use Salt for its multicloud strategy. However, one could also imagine a VMware tool package that includes a Salt minion and can be orchestrated by a future vSphere version. In this way, you could create templates in vSphere, install the operating system packages, and keep them up to date.