Protect privileged accounts in AD

Highly Confidential

In environments characterized by great complexity or the crucial importance of the connected systems, authentication must be clearly regulated. The need for protection is particularly great for privileged accounts such as domain or organization administrators. Active Directory (AD) offers, among other things, the Protected Users group and authentication policies for this purpose.

AD entered the market about 20 years ago with Windows 2000 Server. However, it was to be 13 years before Server 2012 R2 introduced one of the biggest security enhancements in the form of Kerberos authentication for highly privileged accounts. Part of the new functionality, the special treatment of the Protected Users group, was automatically introduced on upgrading the domain function level and caused irritation in some cases. Other features such as authentication policies are still unknown to many administrators.

Protecting Highly Privileged Accounts

For the normal user who logs on to their workstation or a shared computer without system admin rights to perform their tasks with the help of application programs, a standard login by Kerberos is quite good enough. The ticket-granting ticket (TGT) issued at login time is valid for 10 hours by default and is silently renewed when it expires. In principle, you can log in to any client system in the forest, provided the default configuration has not been changed. If older devices are in use, NT LAN Manager (NTLM) authentication is also possible, if necessary, and in most cases, perfectly acceptable.

However, the situation is different for a highly privileged account (Figure 1). "Highly privileged" does not necessarily mean a domain or schema admin. IT managers also need to protect an account adequately that has wide-ranging administrative and data access privileges on a system other than AD itself. An SQL admin has the potential to steal or modify important business transaction data. A file server admin could possibly access confidential drafts from product development, and so on.

Service accounts can also be a valid attack vector. These accounts often have deeper access to resources – both on the computer running the service and on the network – than regular users. What often complicates matters is that the passwords for these accounts do not expire. If the password-protecting data protection application programming interface (DPAPI) in Service Control Manager can be stolen, the attacker can exploit the rights of the account for a long time.

The problem of having to update the service account on many servers at the same time when the password changes can be partially countered by administrators who use group Managed Service Accounts (gMSA): Their password is regularly changed by authorized computers and automatically updated in the Service Control Manager [1]. However, the logon capability of such an account is not limited to certain computers per se, and if the automatically set password is known, it can be used anywhere.

Therefore, it is hugely important for the security of your IT environment to address the following issues for highly privileged accounts:

- On which systems can the account log in? A domain admin, Exchange admin, or SQL admin has no business using the PC in the warehouse, where malware or hackers can sniff their credentials.

- How long can an account use the TGT issued at login time? Is re-authentication necessary when it expires? To mitigate the risk, if a highly privileged Kerberos ticket is stolen, the ability to use it for authentication should be time-bombed.

- For service accounts, who is allowed to request a service ticket against services running under this account? Where is this account allowed to log in? For example, if the service account belongs to the database layer of a three-tier application, the only computers the account needs to log on to are the database servers, and the only computers and users that need to communicate with the database service are the application layer servers and their respective service accounts, as well as database administrators and their workstations. If necessary, it is still important that backup and monitoring systems can connect. Normal workstation PCs, on the other hand, have no reason to communicate directly with the back end of an application.

- For computer accounts, some services run in the security context of the executing machine. Here, too, it is important to be able to limit who is allowed to authenticate against these services and whether NTLM is allowed or Kerberos is enforced in the process.

In the early years of AD, security teams built very complex and nearly unmanageable constructs of permissions, policies, and firewall rulesets to enable this kind of granular segmentation. Server 2012 R2 made this work far easier.

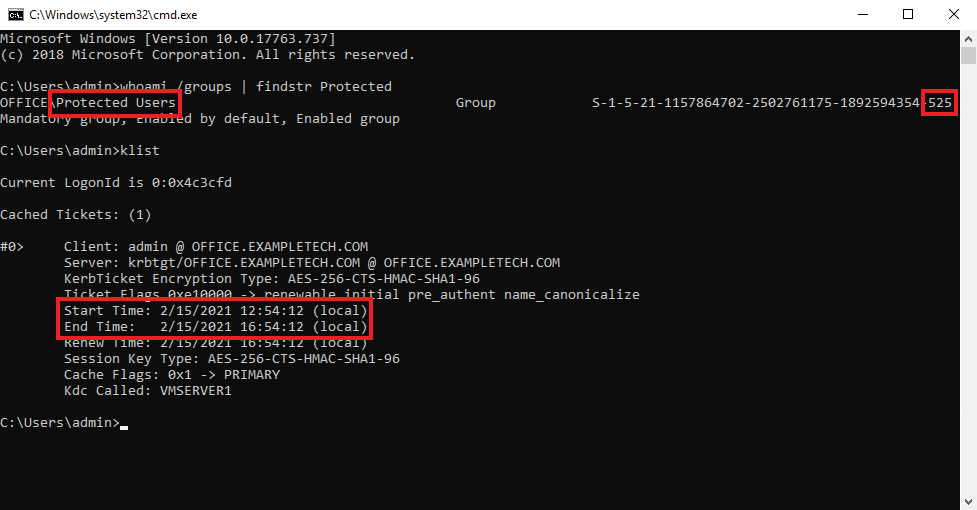

Better Protection Through Protected Users

For highly privileged accounts, an easy way to tighten authentication was introduced with Server 2012 R2. When the Primary Domain Controller (PDC) Emulator flexible single master operation (FSMO) role is transferred to a domain controller running Server 2012 R2 (or newer), Windows creates a new global group – Protected Users – with a unique object ID within the domain (RID) 525. This group is not assigned permissions in AD or on individual systems. That said, the membership of a user account in this group causes some important changes to the behavior of logins for that account:

- None of the login methods (NTLM, Digest, CredSSP, Kerberos) store credentials in the clear or use the highly insecure NT one-way function, independent of the policy regarding delegation of default credentials.

- The login confirmation is not cached, so offline login with a protected account is not possible.

- Kerberos does not generate RC4 or DES keys.

The Protected Users group is available on all server operating systems from 2012 and on all client operating systems from Windows 8. Systems as of Windows 7/Server 2008 R2 were given a security update that also activated this feature in May 2014. However, the protection is only genuinely effective as of Server 2012 R2, which means the following restrictions apply to members of the group:

- NTLM authentication is not allowed.

- Delegation for the account is not allowed, whether limited or unlimited.

- DES or RC4 encryption types for Kerberos pre-authentication cannot be used.

- The TGT is valid for four hours and cannot be renewed. After four hours at the latest, the logged-in user must re-authenticate against a domain controller.

No exceptions exist for specific user groups such as domain or enterprise admins. Completely preventing an account from logging in is theoretically possible just by adding it to the Protected Users group. However, to do this, the domain must have been created before Server 2008, and the user password must have remained the same. As of Server 2008, an AES key is also generated each time the password is changed.

If an account was already created under Server 2000 or 2003 and the password was not changed since then, this account has no AES key and can no longer authenticate. This case is not that unlikely for "emergency admin accounts" that rarely log in. This type of account should not become a member of Protected Users, nor should computer or service accounts.

For all its hardening, the Protected Users group cannot prevent highly privileged accounts from logging on to machines where they have no business doing so. The granularity of the TGT lifetime or NTLM login authorization also leaves something to be desired: The only central policies are for the domain and the hard-wired configuration of the Protected Users group. The authentication policies provide for finer granularity, which is often necessary, and make the limits even more binding.

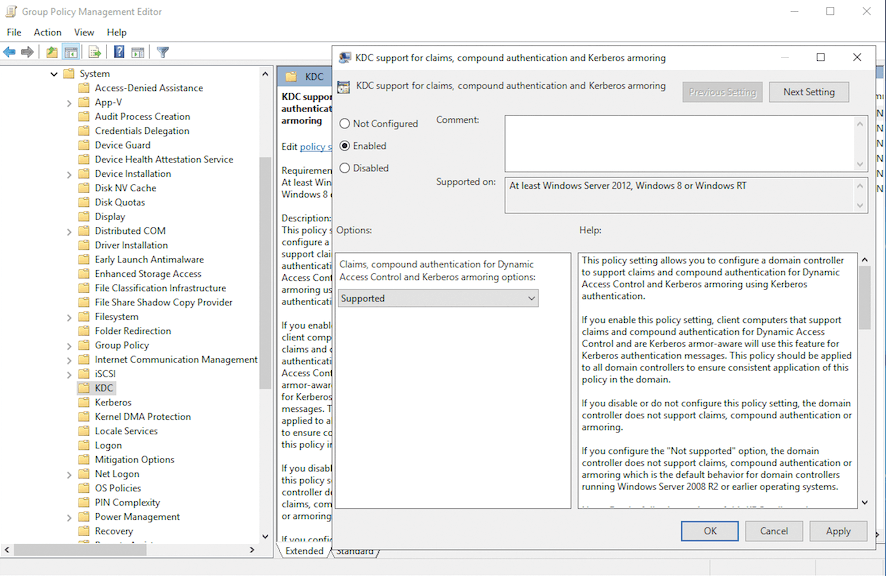

Enabling Authentication Policies

Authentication policies only become available after you upgrade AD to the 2012 R2 domain functional level or higher; then, you can design policies and assign them to different user and computer accounts. To take effect, you need to set two group policy settings. On domain controllers, it's the setting with the long name KDC support for claims, compound authentication and Kerberos armoring in the Administrative Templates | System | KDC computer configuration branch (Figure 2). The possible values are Supported, Not Supported, Always provide claims, and Fail unarmored authentication requests. Select Supported for the optimal combination of protection and compatibility with other systems that use AD authentication.

To the clients – at least those running Server 2012 or Windows 8 or later – assign the Kerberos client support for claims, compound authentication and Kerberos armoring. It is located in the Administrative Templates | System | Kerberos computer branch. It can only be enabled or disabled; thus, compatibility is controlled solely on the domain controller side. To check whether the policy is enabled for a particular device, use whoami /claims. If you have Fine Grained Password Policies (FGPP) in use in your AD environment, you should fast become familiar with how authentication policies work.

On the one hand, this setup allows deviating values to be assigned to individual accounts or groups of accounts for parameters that are normally regulated globally per domain – in this case, the TGT lifetime and NTLM options. On the other hand, these settings are managed from the Active Directory Administration Center (ADAC), which also provides access to the AD recycle bin and dynamic access control.

The authentication policy comprises five sections. Depending on the purpose, entries are not always necessary in all sections:

- User login: TGT lifetime, NTLM login capability.

- Service ticket for user accounts: Which users or computers can request a service ticket for a service running under this user?

- Service registration: TGT life for gMSA.

- Service ticket for service accounts.

- Computer: TGT lifetime, limitations of the application.

For a policy to work for users or gMSA, you need to configure the TGT lifetime for that account type. If in doubt, use the value inherited from the domain or Protected Users membership.

If you enter a different value here, it applies. This way you can also set a longer TGT lifetime for the members of the Protected Users than the hard default of 240 minutes.

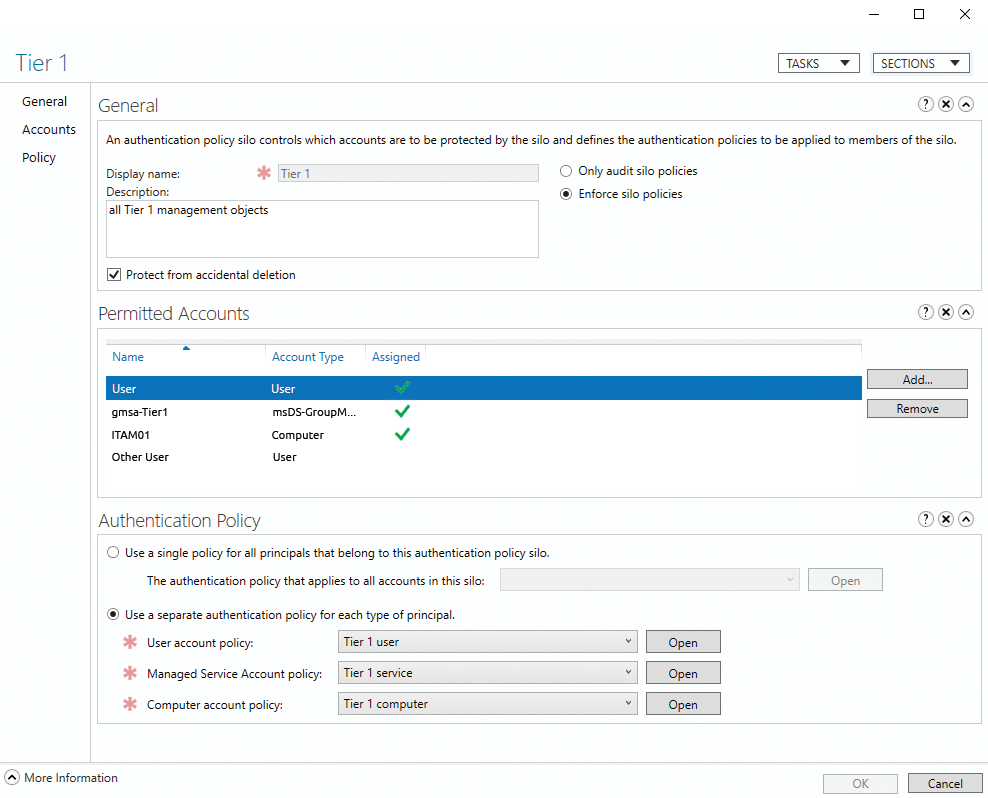

Group and Conquer: Policy Silos

One of the most common use cases for authentication policies is that of creating administrative tiers or application silos, where a well-defined set of user and service accounts are allowed to log on to a well-defined set of computers. You map such silos with authentication policy silos, to which you can assign users, managed service accounts (gMSA), and computers. The silo then determines which authentication policies apply to the silo members: Either one policy for all types of accounts or separate policies per account type.

Policies and silos can be assigned to managed service accounts by PowerShell only. The Set-ADAccountAuthenticationPolicySilo cmdlet can be used for both operations. In both cases, you have to use the -Identity argument to specify the account to assign. The second parameter is either -AuthenticationPolicy or -AuthenticationPolicySilo, depending on the desired assignment. Authentication policies can be assigned to the same security principal both directly and through policy silos (Figure 3). Policies from the silo always take precedence over the directly assigned policies.

Another useful aspect of silos is the option to use them as a criterion in selecting allowed users and computers (e.g., for issuing service tickets). For example, you can authorize a user account within its own silo to log in interactively. However, if a service is running under that account, only devices from another specific silo can authenticate to that service.

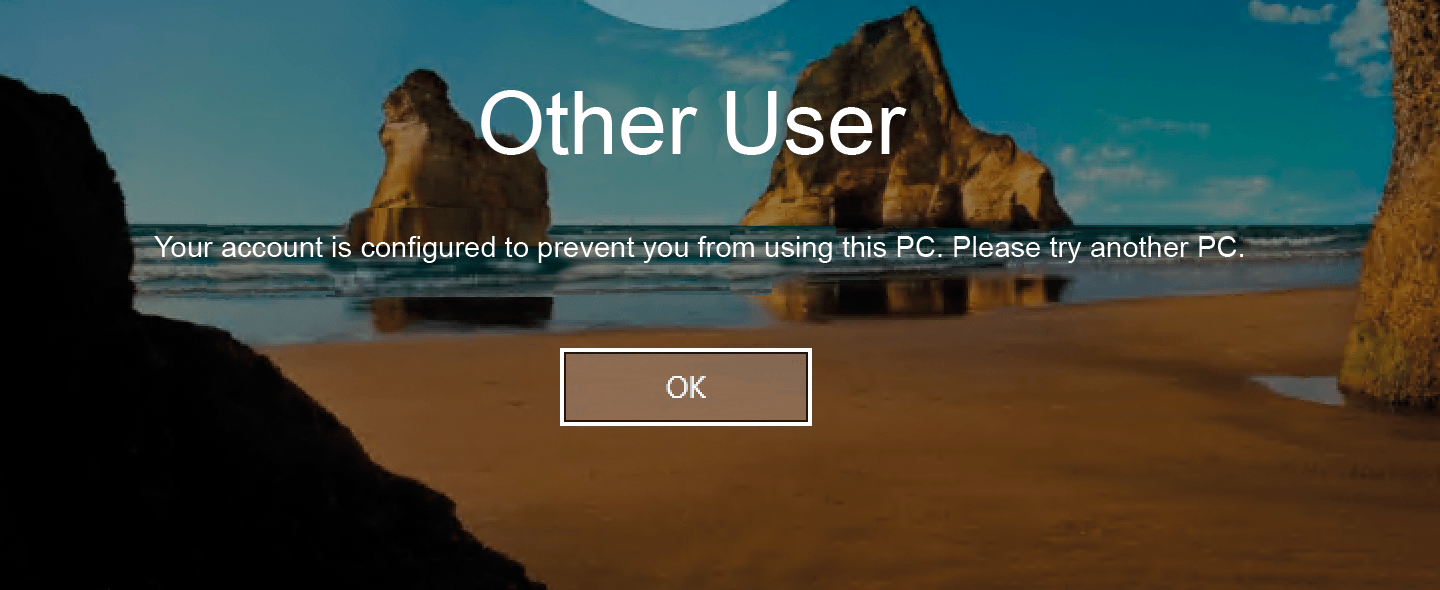

Build an Island

The simplest deployment scenario for authentication policies is to build an authentication silo – that is, a group of computers and a group of users who are the only ones who can log in to those computers (and only there). The following examples show how you can achieve this:

- Create an authentication Island policy.

- Create an authentication policy silo Island silo and set the Island policy for all account types.

- Assign the designated computers and users to the Island silo.

- Edit the Island policy and set the TGT lifetime for user accounts to an appropriate value (600 minutes is the AD default; 240 minutes is the default for Protected Users).

- In the Computer section, create the Access Control Conditions User – Authentication Silo – equals – Island silo.

- Create the same condition in the User section.

As of now, only the Island users can log in to Island computers; all others will receive an error message indicating the authentication firewall. When Island users try to access machines outside their island, they get an error message (Figure 4). For the settings to take effect, you have to restart the Island computers.

Monitoring and Troubleshooting

Microsoft has provided a special event log channel Microsoft\Windows\Authentication for monitoring the Kerberos protection functionality. On the domain controllers, the authentication attempts of the protected users are recorded in the log channels Microsoft\Windows\Authentication\ProtectedUserSuccesses-DomainController and Microsoft\Windows\Authentication\ProtectedUserFailures-DomainController.

Failed authentication policy activity can be found in the Microsoft\Windows\Authentication\AuthenticationPolicyFailures-DomainController channel. Regardless of whether the Protected Users group contains members or you have created authentication policies, these protocols are disabled for now. You should also enable them for troubleshooting purposes only by selecting Enable Log from the context menu of the respective event log. Alternatively, you can issue the following PowerShell command on each domain controller:

$logname = "Microsoft-Windows-Authentication/ProtectedUserSuccesses-DomainController" $log = Get-WinEvent -ListLog $logname $log.IsEnabled = $true $log.SaveChanges()

All three channels can be enabled similarly. On the affected member machines, you need to enable the client event log. Again, the fastest way to do this is with PowerShell:

$logname = "Microsoft-Windows-Authentication/ProtectedUser-Client" $log = Get-WinEvent -ListLog $logname $log.IsEnabled = $true $log.SaveChanges()

The logs are very verbose, so their size can quickly reach the default configured limit of 1MB if you have a large number of protected accounts. You can set the size immediately on enabling by adding the $log.MaximumSizeInBytes = 128MB line before SaveChanges() in the PowerShell code above. This addition increases the maximum log size to 128MB. Other useful tools for troubleshooting Kerberos authentication include klist [2] and whoami [3] – specifically, whoami /claims in this case.

When troubleshooting, always keep in mind that authentication policies, as the name suggests, control authentication. All other mechanisms evaluated after successful authentication, such as the revocation of local logon rights or the logon restrictions in AD (attributes logonHours and userWorkstations), remain in force.

Conclusions

Protected Users and authentication policies allow highly granular control of the user login for highly privileged accounts. Because these mechanisms act directly on the Kerberos protocol, they are more robust against unwanted changes than other approaches used to influence login behavior. Accounts are managed by the AD Management Center or PowerShell and are distinguished between User, Computer, and Service (gMSA) accounts.

Even these new ways of securing for highly privileged accounts do not relieve you of the responsibility of implementing the least privileges principle and carefully monitoring login behavior in your environment.