VMware connections to the Kubernetes market

Supertanker

Admins understand that simply operating containers is not enough. Instead, purpose-designed container orchestration is also necessary, which is where the popular Docker was seen to be lacking. Google's Kubernetes jumped into the breach and developed a busy life of its own far removed from Docker.

For decades, VMware was the industry leader in virtualization, offering a virtualization environment from a single source. VMware vSphere, the server virtualization platform, easily docks with other VMware products and has even jumped on the OpenStack bandwagon with a kind of translation component between the official OpenStack APIs and vSphere in the form of VIO – VMware Integrated OpenStack.

It was strange for VMware to have seemingly been asleep through most of the Kubernetes hype. Ultimately, Kubernetes with its containers in the background – no matter which run time they use – are tantamount to a central attack on the core of VMware's business (i.e., full virtualization and paravirtualization).

Sleeping on the Kubernetes threat is now a thing of the past: Project Tanzu is about to become the VMware toolkit for Kubernetes, claiming to integrate Kubernetes seamlessly with the existing VMware framework.

Some of the tools used in Tanzu are already available under an open source license; further components will follow in the coming months. It's worth taking a closer look. What are VMware's tactics with regard to Kubernetes? What can VMware users expect when it comes to Kubernetes? Where does VMware's love of container orchestration end?

Integration Is Not Easy

Even if it looks to be so at first glance, it is not easy for VMware to integrate Kubernetes and possible additional programs into its own portfolio. After all, Kubernetes (also called K8s) seems to do very well without real virtualizers like VMware or KVM – that's one of the software's core promises.

Additionally, Kubernetes deliberately excluded many concepts that were the downfall of other approaches (e.g., OpenStack). Kubernetes does not even provide for multiclient capability. Instead, it suggests that individual Kubernetes clusters should simply be rolled out for each customer. Although this method leads to some overhead at the Kubernetes level, you need far fewer technologies like software-defined networking (SDN) in the setup to achieve client separation. If VMware wanted to find a gap in this construct for itself, one thing was clear: It wouldn't be easy.

In the search for a way out of the dilemma, VMware came across an approach that many other vendors have already chosen for themselves: If the trend is to run many Kubernetes instances at the same time, then the admin needs a tool that offloads some of the work. Such a tool is now becoming the core of VMware's strategy to penetrate the Kubernetes market.

Project Tanzu

VMware, which now belongs to the Dell EMC Group, presented its strategy for the Tanzu project at its in-house VMworld in San Francisco at the end of August 2019. The company announced several tools that will make it easier for admins to operate Kubernetes while simplifying development in Kubernetes [1].

Tanzu basically comprises three concepts: Tanzu Mission Control allows the efficient management of several Kubernetes clusters, whereas Enterprise PKS and Essential PKS make it possible to roll out the Kubernetes distribution – a VMware acquisition called Pivotal – in private as well as public environments.

Controlling Kubernetes

VMware has made a name for itself over the past decades by always equipping its products with flashy graphical tools that abstract complex technology. Even technically complex processes could be controlled in simple graphical user interfaces (GUIs), and as the icing on the cake, meaningful statistics were also available in the form of charts.

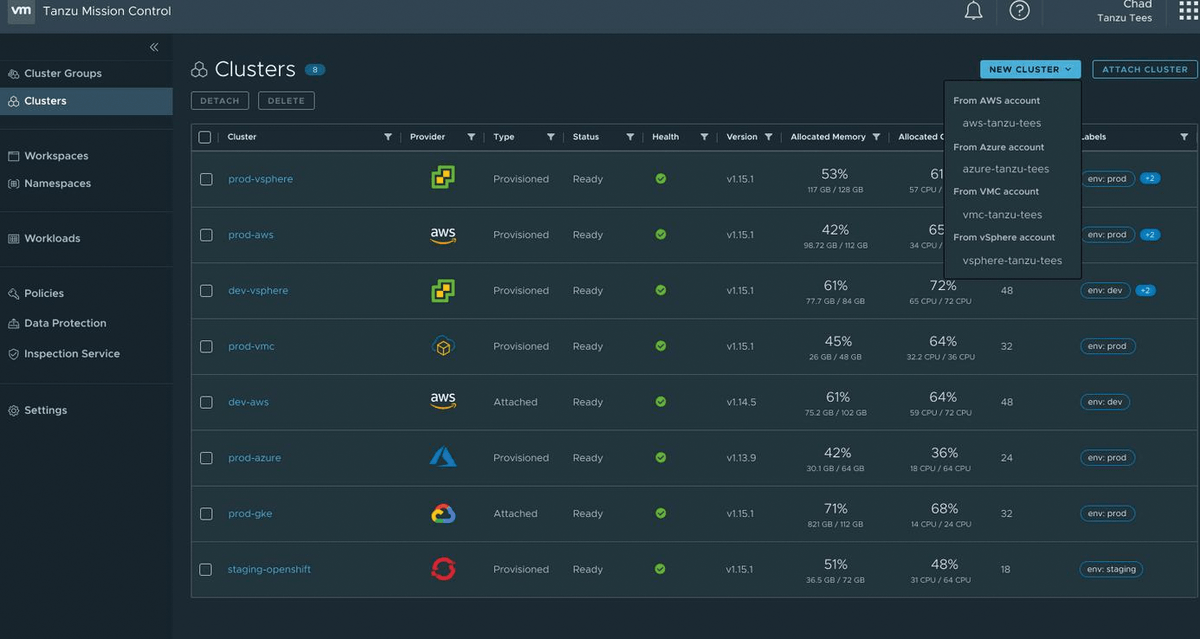

Therefore a graphical tool is part of Tanzu, too: Tanzu Mission Control (Figure 1), which is primarily used to connect different Kubernetes instances at different destinations and control them centrally.

Basically, Tanzu Mission Control (MC) differentiates between cluster groups and clusters: A cluster is always a Kubernetes instance, and an admin creates groups on the basis of various parameters, such as the type of cluster (i.e., whether it has been rolled out from AWS, is an Azure-Kubernetes cluster, or is a separate on-premises solution). New clusters can also be started from within Tanzu MC, so if you already have active Kubernetes instances, you can integrate them into a new instance of Tanzu, if desired.

Put simply, Tanzu wraps itself around the Kubernetes instances under its control. Tanzu also offers the classic VMware nomenclature for Kubernetes to which admins are accustomed from vSphere. One example is the integration of a comprehensive policy framework, including user administration, that allows specific permissions to be defined down to the level of individual actions.

VMware has always impressed its customers by facilitating compliance and implementing centralized policies, because the ESX hypervisor, vSphere, and other VMware products (e.g., VMware vSAN software-defined storage or NSX software-defined networking) can span all levels of the installation in classic VMware setups and control them accordingly.

However, compliance considerations are not the only elements in Tanzu that VMware is using to fish for customers. A complement to this is a kind of orchestration for Kubernetes instances; admins can centrally store configurations for the container orchestrator in Tanzu. Tanzu then applies the configs to the Kubernetes instances under its control. If Tanzu itself starts a new Kubernetes environment, the same happens there.

What Tanzu Can Control

Anyone who has ever dealt with the various public cloud providers will be aware that all the major players no longer require their customers to roll out Kubernetes themselves. Instead, AWS, Azure, and others have ready-made Kubernetes resources that can be rolled out completely in their respective environments.

For the moment, it seems that these very resources are Tanzu's primary target group, because as soon as the admin has stored the appropriate credentials, the tool connects to Google, AWS, and Azure and then discovers the clusters that are already running. Launching a new Kubernetes instance with Tanzu is realized by reference to these resources in the respective cloud. The advantage for the admin is obvious: All active instances in the project for which credentials were entered are immediately visible and can be controlled by Tanzu at the push of a button.

Tanzu connects directly to active Kubernetes instances by specifying the Kubernetes API data individually for each instance, which can take some time depending on the head count. Ultimately, however, this use case is not what Tanzu aims for.

VMware obviously will not be happy if only public clouds are meaningfully integrated into its own tool set. That's why VMware is now launching its own Kubernetes products, which of course are just as well integrated in Tanzu – more on this in a moment. I should mention beforehand that the Tanzu GUI is not just designed for Tanzu management. A GUI designed especially for admins and developers satisfies their requirements without manual intervention.

Specifically, this means that if the policy framework is built accordingly, non-admin users can start Kubernetes clusters easily with Tanzu. Additionally, Tanzu is aware of the resource "workload," which leans toward continuous integration/continuous deployment (CI/CD) and implies the use of Kubernetes.

Old Friend: Pivotal

Without a doubt, VMware can be regarded as a success story: For decades, the company has maintained solid partnerships with a large number of major technology companies worldwide that translate into economic success. Of course, the VMware executive board is aware that they will not get very far with mere management tools for VMware only.

Even if VMware had the most sophisticated container management system in the world, commercial Kubernetes distributions like OpenShift offer their own GUIs and provide a complete Kubernetes in the vendor's preferred flavor. Customers might want to link this to Tanzu, because it allows the management of various Kubernetes clusters. Undoubtedly, though, they would not be willing to pay the same amount of money that VMware is asking for its virtualization tools.

VMware quickly understood that, when it came to Kubernetes, they had to come out of their shell themselves and get a product up and running quickly. VMware is by no means the only traditional company venturing into the world of Kubernetes. For a few months now, providers that one would never have expected have even been appearing on the market with Kubernetes distributions, such as NetApp.

However, if you expect VMware to build its own distribution for the container orchestrator, you are mistaken. Because VMware is now part of Dell EMC, who has a keen interest in ensuring that VMware remains successful in bringing hardware to the public through this channel, the company boasts well-filled vaults, and they tapped into their savings a few months ago to acquire one of the pioneers in the container industry: Pivotal.

Correspondingly, VMware has two Kubernetes products in the starting blocks today. VMware Essential PKS is aimed at those who want the purest possible Kubernetes. VMware Enterprise PKS, on the other hand, addresses the typical VMware clientele who not only want the solution per se, but also want to integrate with control systems the complete NSX experience and seamless support for the integration of AWS and the like.

VMware Essential PKS stands out from the ranks of VMware products, in that it's closely oriented on the original Kubernetes. Fundamentally, Essential PKS is a basic Kubernetes distribution that doesn't deviate from the standard specifications of the container orchestrator in terms of networking or storage. Moreover, support is available for both the product and applications that can be designed on the basis of the product.

Enterprise PKS

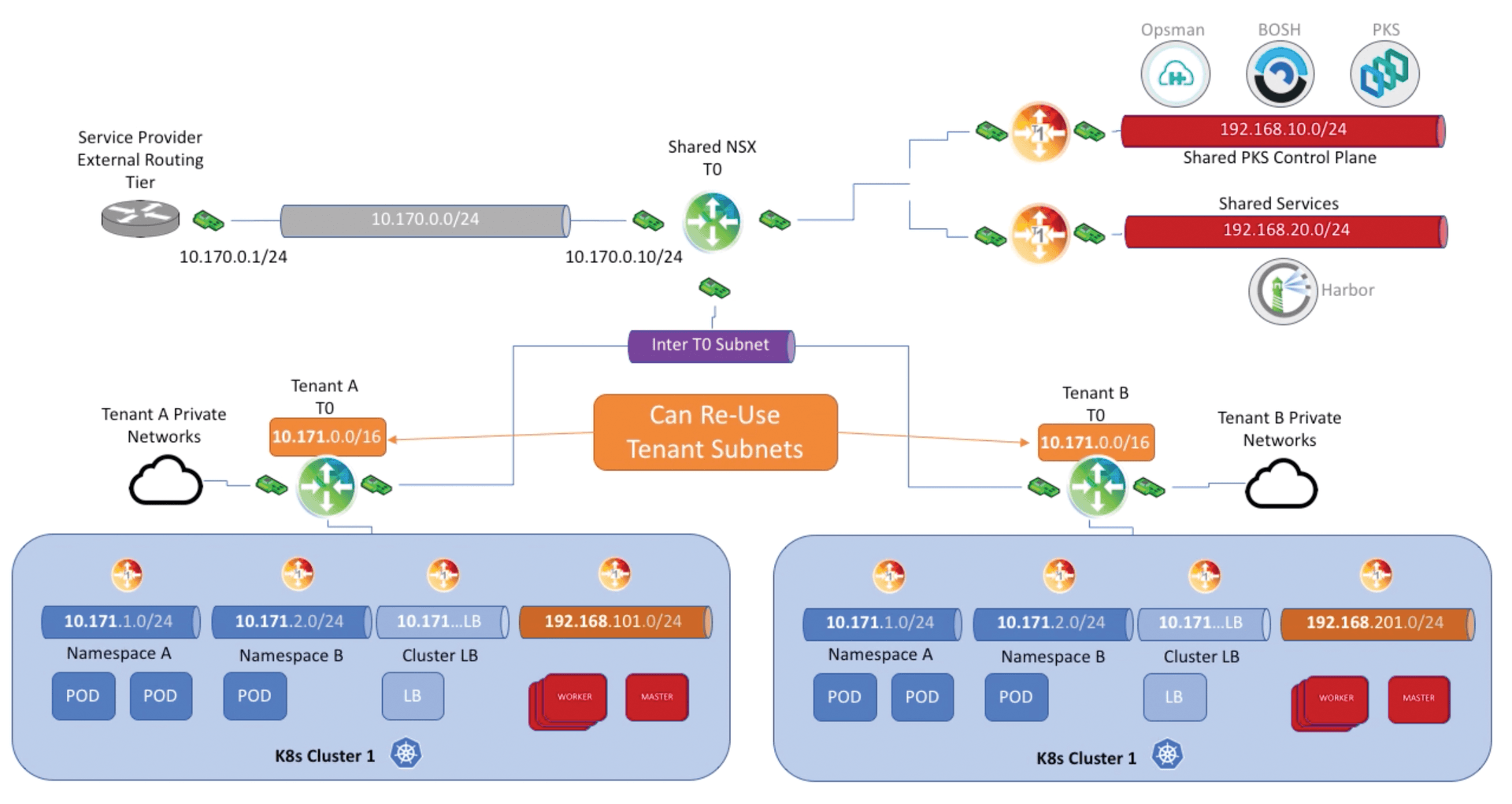

On the other hand, if you're used to no-worry packages, you'll feel more comfortable with the Enterprise PKS version (Figure 2) of the VMware Kubernetes distributions. Just why is illustrated by a look at the ecosystem that VMware likes to build for its customers. Virtualization has long since ceased to be the only factor, and other components play an important role.

For example, the Ceph object store has no sensible way to connect to VMware, but because VMware itself is now active in the cloud and looking to sell scalable solutions to its own clientele, it has an alternative to Ceph – vNAS. This proprietary implementation of seamlessly scalable storage supports hyperconvergence, shaping the disks on each node into a large virtual store from which clients can access all nodes. Importantly, they can do so transparently, at least from the user's point of view. The user simply specifies that a virtual machine (VM) should have persistent storage – they don't need to know how VMware implements the technology in the background.

The situation is similar for the network. If you have the VMware cloud package, you implicitly also have VMware's own SDN solution NSX, which was written by the same authors as Open vSwitch, considered to be a quasi-standard in open source SDN. However, NSX has far more functionality than classic Open vSwitch, and control by vSphere makes it much more versatile. Multicloud approaches are no problem, for example, where the administrator distributes individual parts of the workload to different public clouds or an on-premises cloud. vSphere builds a seamless virtual network between the individual parts of a setup without the administrator having to do anything special.

Anyone who opts for the Enterprise PKS edition of the VMware Kubernetes distribution gets a Kubernetes that is just as perfectly integrated into these systems as a regular VM. In such a setup, Kubernetes integrates with NSX (e.g., with its own plugins) so that multicloud workloads are no problem, even with Kubernetes. If you want the classic VMware experience, you're probably better off with this product. In return, however, the bill from VMware for the combination of product and support will be far larger – although VMware customers may be used to this.

In-Depth Integration

If you are already a VMware customer and decide to follow VMware's foray into the world of Kubernetes, you can expect in-depth integration in return for hard cash. After all, VMware thrives with customers who have made themselves comfortable in the VMware universe and have few reasons to reconsider their decision. Specifically, this means that anyone wanting to roll out a Kubernetes cluster in their local environment can do so in existing vSphere clusters through Tanzu MC. The containers then run on ESXi hosts, mostly on VMs.

From an administrative point of view, this scheme makes sense. Admins will normally want to manage the complete life cycle of a cluster based on Kubernetes automatically and without manual intervention, which can be done easily with the standard VMware interfaces and the usual tools. By the way, this approach is by no means specific to VMware: People who operate large numbers of Kubernetes clusters occasionally resort to OpenStack because VMs in clouds can be provisioned quickly. In contrast, it takes considerably longer to roll out real metal.

However, this approach also involves considerable overhead in terms of resources. If you run Kubernetes on real VMs, you have the overhead of the VM on the one hand and the container on the other. For years, there has therefore been a desire to run containers on hardware instead of intermediate VMs while retaining the management solutions already known from solutions such as vSphere or OpenStack.

At the end of the day, an ESXi host logically ends up running an agent that starts VMs. If this was converted so that it could instead create containers from scratch, the goal would be achieved. VMware doesn't need to worry about problems like SDN or the central availability of storage, because vSAN and NSX exist – and could simply continue to be used in such a setup.

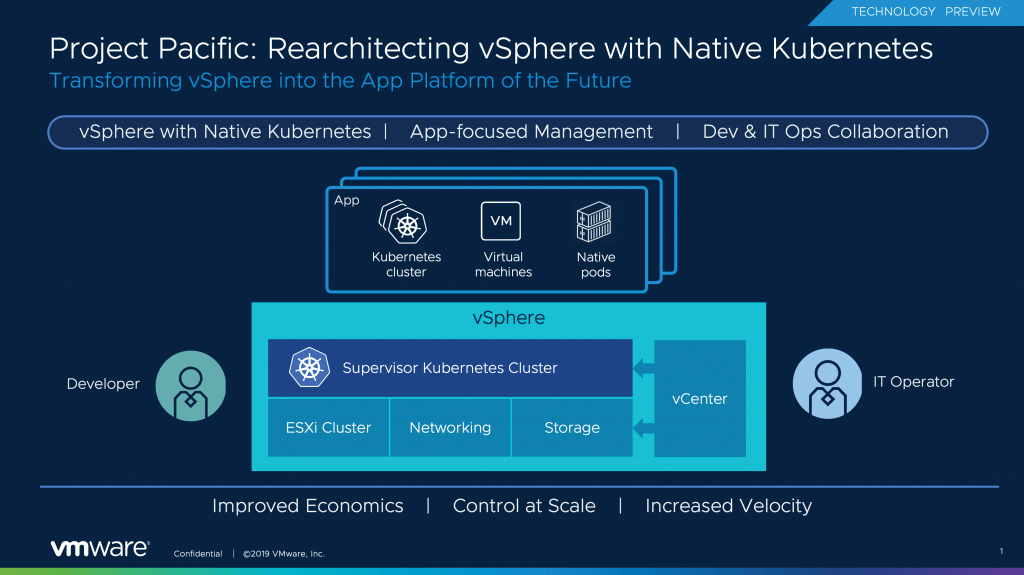

vSpherelet on Approach

Not surprisingly, an announcement from VMware refers to this very approach. In the future, VMware will provide vSpherelets alongside the classic Kubelets that allow a bare metal node to be used for running Kubernetes containers in vSphere. The overhead described above will therefore be history. VMware is even a little earlier in the game in this respect than Kubernetes itself, which is working on similar approaches, although not specifically tailored to VMware.

A vSpherelet makes the integration of VMware and Kubernetes even tighter, at the price of further vendor lock-in. Once you run Kubernetes in the context of such a setup, there is almost no chance to back out of it.

VMware markets the whole thing under the name Project Pacific (Figure 3). The central goal is to make vSphere a central application platform of the future. Heads up, people: Obviously, VMware is also assuming that in the future far fewer companies will be interested in classic infrastructure as a service (IaaS) and that platform (PaaS) and software as a service (SaaS), for example, will set the pace instead.

Open Source Role

Another interesting factor in the context of Tanzu at VMware is the launch of a new GitHub repository [2] parallel to the official Tanzu launch that makes various open source components from Tanzu available under an open license. Thus far, VMware has not exactly been considered an open source pioneer – reason enough to take a closer look at the components on offer. The tools clearly also offer useful functions outside of VMware setups.

Under the name Velero, for example, VMware offers a product that takes care of backing up Kubernetes instances and migrating complete Kubernetes installations. Because virtually all container workloads are virtualized anyway, this kind of migration is not uncommon. For example, if you get a better environment at AWS than at Azure, you might want to move all of your active Kubernetes instances. If you need disaster recovery, you will be interested in the part that copies data from A to B. Velero assumes precisely the role of a general-purpose tool for backups and migration in Kubernetes. VMware even provides a plugin that allows Velero to integrate directly with the backup capabilities of Google's container platform, with plugins for the other vendors expected to follow soon.

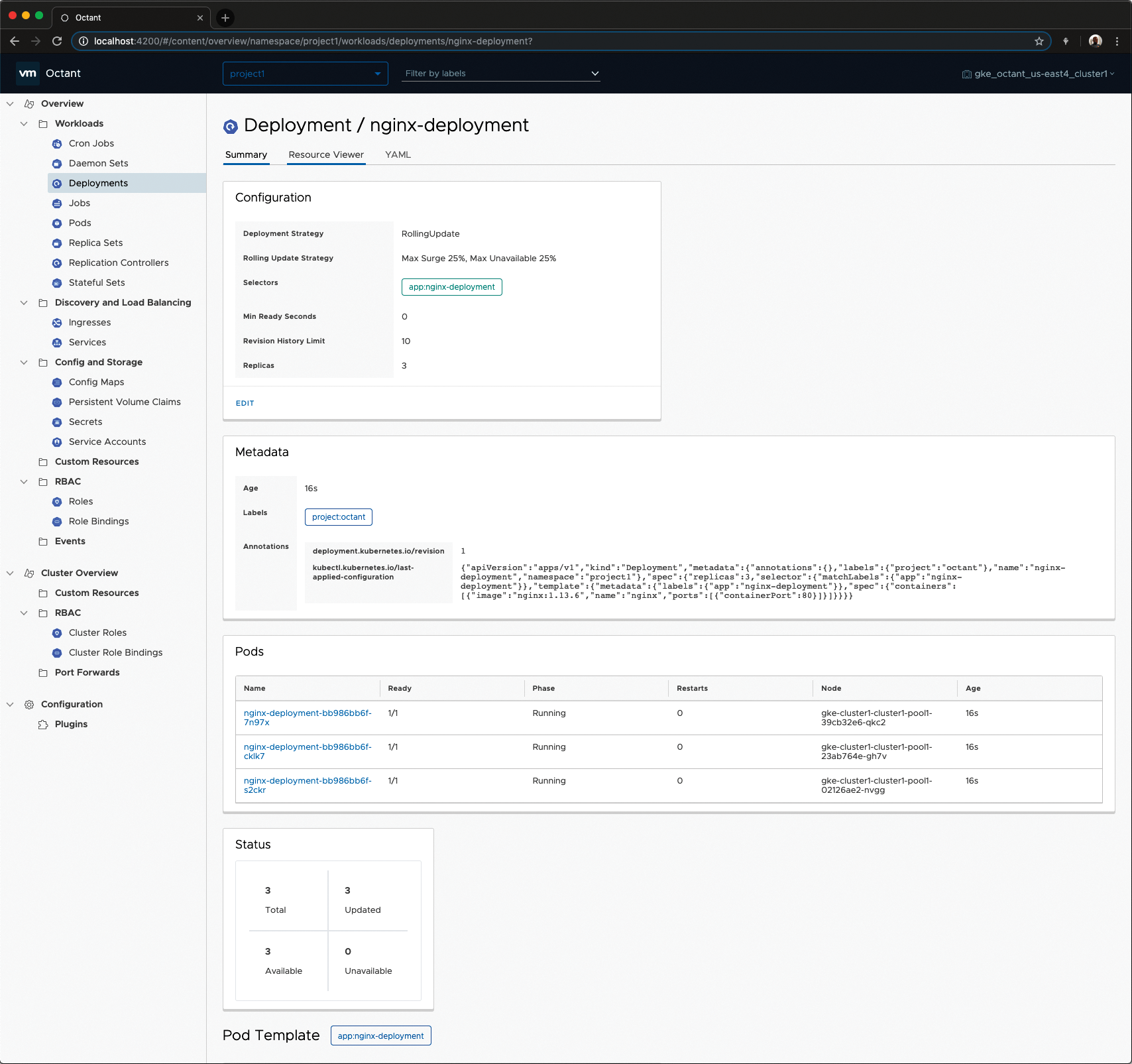

Octant (Figure 4), no less practical, allows admins to check the state of an instance of Kubernetes in a graphical console. Octant obviously serves as the foundation for Tanzu MC, because some views are almost identical in Octant. However, nothing can be changed in Octant: Look but don't touch. No problem. Octant quickly provides a better overview than many other tools on the market, and if you are looking for good visualization of your Kubernetes instances, you will want to take a closer look.

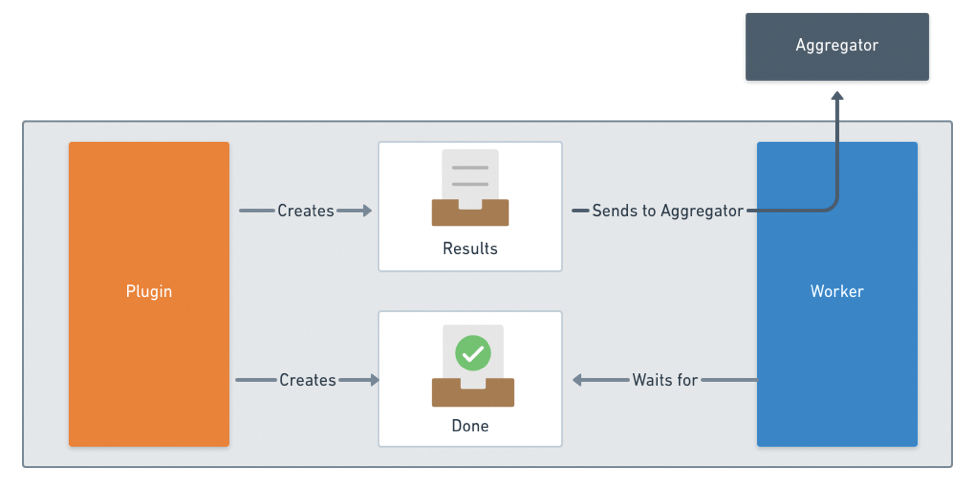

Last but not least, do not forget Sonobuoy (Figure 5), which informs the admin about the state of a Kubernetes instance – and not just the mere facts, but metrics, such as the performance of individual services. Sonobuoy collects the data ad hoc on the basis of existing Kubernetes tests to present an overview at the end of the process.

All three components presented here communicate exclusively with the Kubernetes API or the API of the cloud provider who operates Kubernetes as a resource, with no need for any VMware products. I recommend that Kubernetes admins take a closer look at these tools.