Implement your own MIBs with Python

DIY MIBs

If you think of Wikipedia first when considering a freely expandable, hierarchical knowledge database, you are not totally wrong, but you have overlooked one classic example: The Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP). This time-honored protocol can also conjure up a very wide range of very different information through a formalized protocol and Management Information Base (MIBs) modules.

MIBs are readily available from device and software manufacturers, but application developers looking to expose the internal metrics of their software can create them, as well. They can be equally useful for sys admins who want to monitor complex infrastructure setups such as DNSSEC. At first glance, implementing your own MIB might seem complex, but with the right tools, it's not that difficult. This article shows how to create a MIB for monitoring the system-on-a-chip (SoC) temperature of a Raspberry Pi with an easy-to-use Python module.

Management Information Base

SNMP can be compared in some ways to the Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP), another Internet classic. Both are network protocols that describe how to access information. In the case of LDAP, you consult an LDAP directory, which can take very different forms. In the case of SNMP, the Management Information Base that is an aggregation of implemented MIB modules can contain a wide range of information, from routing tables to the utilization level of filesystems, and from fan speeds to configuration states.

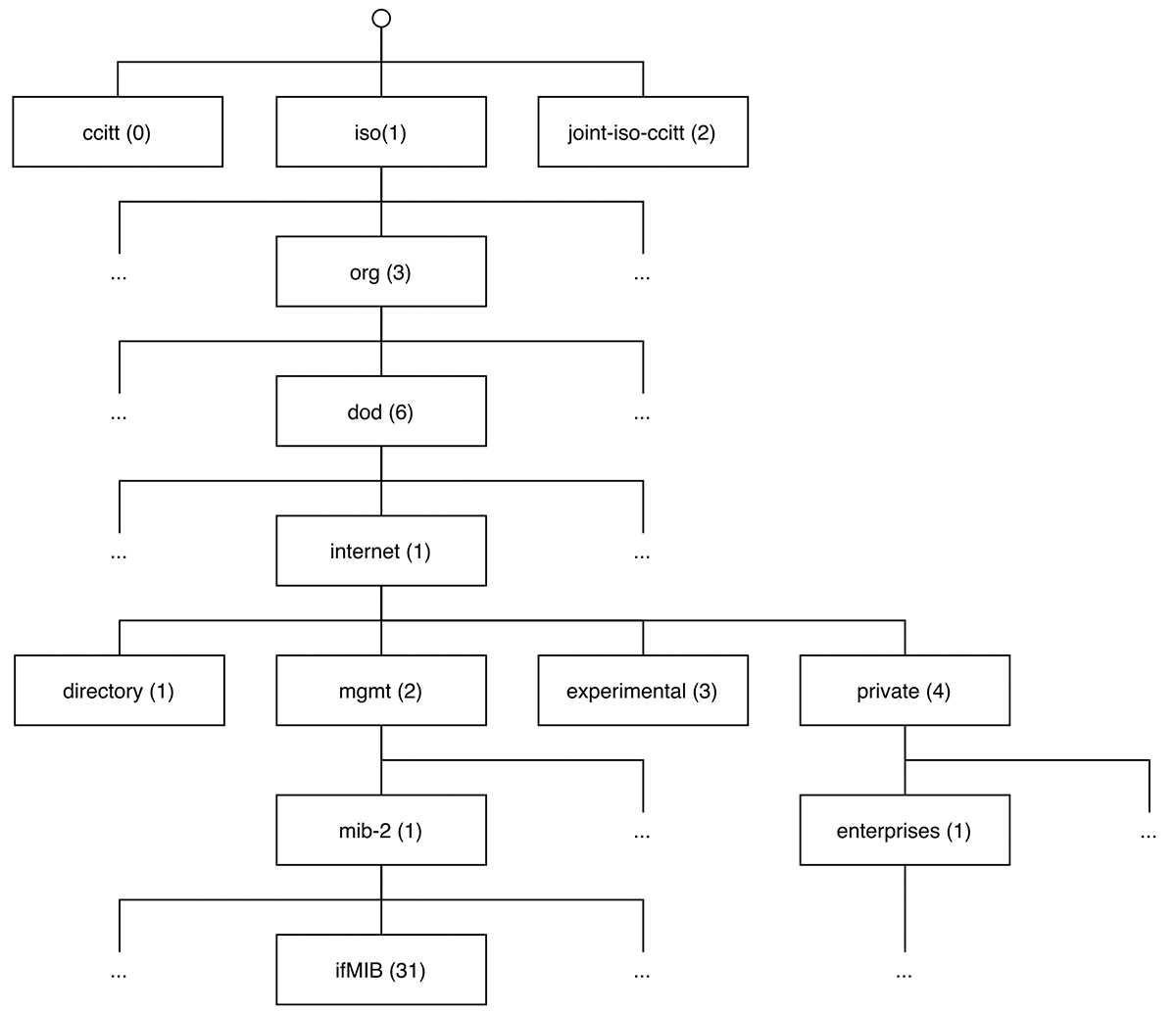

It's probably best to imagine the MIB as a collection of carefully defined objects and messages – in SNMP-speak this is Managed Objects and Notifications – that form a tree-like structure below a root node. Both are identified by their respective position in this tree through an object identifier (OID), which describes the path from the root node along the branches to the managed object or notification.

Each OID starts with a dot, representing the root node, followed by numbers, again separated by dots, that represent the branches and – at the end – the leaf of the tree. A rather short OID could be .1.3.6.1.2.1.31. There is an analogy to IP addresses here: Because it's difficult to remember an IP address as a series of numbers, the Domain Name System (DNS) was invented. In the case of OIDs, so-called MIB modules – text files also often called MIBs – likewise assign a name to each numeric component of an OID. For example, the above OID is easier to read as:

.iso.org.dod.internet.mgmt.mib-2.ifMIB

This example OID also demonstrates that the MIB tree (Figure 1) has a defining order. The described object is located, starting from the root node:

- in the branch of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), iso (.1),

- in the branch for designated organizations, org (.3),

- in the branch of the US Department of Defense, dod (.6),

- in the branch for TCP/IP-based Internet, internet (.1),

- in the branch for network management, mgmt (.2),

- in the branch mib-2 (.1), and, finally,

- under the name ifMIB (.31).

MIBs can do much more, however. They can define entire sub-trees of the MIB, dock on top of existing trees, and often be extended at the bottom by other MIBs. At the top of the tree is SNMPv2-SMI (Structure of Management Information): Compliant to the specifications in RFC 2578 [1], it defines the .iso.org.dod.internet (.1.3.6.1) sub-tree, under which, the sub-trees directory (.1), mgmt (.2), experimental (.3), and private (.4) reside.

In practice, everything of interest is located within these sub-trees. Whereas the first three are characterized by vendor-independent standards, if you look at private (4) its enterprises (1) subtree is host to vendor-specific sub-trees with numbers assigned by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) [2]. MIBs also define syntax and semantics, assigning data types to the objects of their sub-tree and defining their own data types, if necessary – either scalar types (virtually anything that is not a table) or tables that represent a collection of scalar objects in rows. For example, the Interfaces Group (IF) MIB defined in RFC 2863 [3] describes the ifTable, a table with all interfaces of a monitored system, and its statistics, such as the number of sent and received packets.

Embrace and Extend

A MIB thus ultimately simply represents a collection of definitions. However, a program known as an SNMP agent is needed to collect and provide this information. With network devices such as switches, the agent usually remains invisible because it is part of the firmware, and the question of extending it with your own MIBs simply does not arise.

In the case of a Linux system, like the Raspberry Pi in this example, things look different. Here, the snmpd SNMP agent implements a fixed selection of MIBs (Table 1), but it can be extended in various ways.

Tabelle 1: MIBs Managed by snmpd

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

At the very beginning, you have to install the packages needed for this project on the Raspberry Pi:

$ apt-get install snmp snmpd snmp-mibs-downloader smitools

The easiest way to extend it is with a minimal snmpd configuration file:

rocommunity rpitesting extend rpitemp /bin/cat /sys/class/thermal/thermal_zone0/temp

For this first test, it makes sense to back up any existing /etc/snmp/snmpd.conf file.

If you now start snmpd, a temperature value of the Raspberry Pi Broadcom SoC can be obtained with the command:

$ snmpget -v2c -c rpitesting -Ovq localhost NET-SNMP-EXTEND-MIB::nsExtendOutputFull.\"rpitemp\"

The result is the current temperature, multiplied by 1,000 so it can be processed as an integer.

This works because the extend module of snmpd uses NET-SNMP-EXTEND-MIB to create matching MIB entries dynamically below the .iso.org.dod.internet.private.enterprises.netSnmp.netSnmpObjects.nsExtensions sub-tree for each configured command (Listing 1).

Listing 1: snmpwalk

$ snmpwalk -Of -v2c -c rpitesting localhost NET-SNMP-AGENT-MIB::nsExtensions .iso.org.dod.internet.private.enterprises.netSNmp.netSnmpObjects.nsExtensions.2.1.0 = INTEGER: 1 .iso.org.dod.internet.private.enterprises.netSNmp.netSnmpObjects.nsExtensions.2.2.1.2.7.114.112.105.116.101.109.112 = STRING: "/bin/cat" .iso.org.dod.internet.private.enterprises.netSNmp.netSnmpObjects.nsExtensions.2.2.1.3.7.114.112.105.116.101.109.112 = STRING: "/sys/class/thermal/thermal_zone0/temp" [...]

By the way, the double-colon notation shown here is a short form commonly used by all Net-SNMP tools. The MIB name comes first; the name of the managed object or notification for which you searched and which is defined in this MIB is at the end. Both MIB names and object and notification names must be unique within a MIB; therefore, the combination of the two is unique, as well. The extend mechanism built into snmpd is easy and quick to implement, but it also has some disadvantages. It is best suited for simple, unstructured information. You could easily call another script with another extend line in snmpd.conf that returns, for example, the value of a sensor accessible via I2C. However, with no caching, each query of an object implemented through extend triggers a separate execution of the configured command, which might take a bit of time under certain circumstances. Also, you might want to present information in a more structured form than the inevitably generic NET-SNMP-EXTEND-MIB allows.

To avoid these disadvantages, you need to do two things: Design your own MIB for the desired purpose and implement it in a more flexible way than with extend.

Basics for Custom MIBs

MIBs are written as ASCII text files, and with a standard Net-SNMP installation they can usually be found in /usr/share/snmp/mibs/. The files follow a language called Structure of Management Information (SMI). SMI – currently at version 2 – comprises an adapted part of the Abstract Syntax Notation (ASN.1) that is a shared standard of the ISO and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Telecommunication Standardization Sector (ITU-T) used primarily for communication technologies (e.g., for GSM or X.509 certificates), but also for LDAP.

In principle, a MIB comprises a series of definitions in the format:

Name Keyword [Parameters] ::= Value

The different parts can extend over several lines depending on the keyword. Keywords can have additional mandatory or optional parameters. Listing 2 shows an initial basic structure of the RASPI-MIB.txt MIB.

Listing 2: Basic MIB Structure

RASPI-MIB DEFINITIONS ::= BEGIN ----------------------------------------------------------- -- RASPI-MIB for monitoring the temperature of the RasPi-SoC ----------------------------------------------------------- END

The DEFINITIONS keyword assigns the name RASPI-MIB a specific value: everything that follows between the keywords BEGIN and END. In this listing this value is not much, because everything between two single pairs of hyphens or between a pair of hyphens and the end of a line is taken as a comment and ignored. DEFINITIONS also diverges from other keywords, in that you can use a leading capital letter and hyphens for the associated name. According to SMIv2, both are prohibited for all other names.

However, another exception needs to be investigated first: The IMPORTS keyword. It does not follow the described format at all and, much like similar keywords in C and Python programs, is dedicated to the task of importing existing definitions from other MIBs. A typical IMPORTS block that loads needed definitions might look like Listing 3.

Listing 3: Imports

-- Imports

IMPORTS

MODULE-IDENTITY, OBJECT-TYPE, Integer32

FROM SNMPv2-SMI

netsnmpPlaypen

FROM NET-SNMP-MIB;

The first part of a MIB is always a module definition, which contains a large amount of information about the MIB. In the C language, you would define a structure to convey the information, whereas in ASN.1, you use a macro. Macros are used to construct data types and values beyond the ASN.1 standard repertoire. The MODULE-IDENTITY macro defined in SNMPv2-SMI is used as shown in Listing 4.

Listing 4: MODULE-IDENTITY Macro

raspiMIB MODULE-IDENTITY

LAST-UPDATED "202005060200Z"

ORGANIZATION "None"

CONTACT-INFO

"Editor:

Careful Reader

Raspberry-Pi-Way 42

10487 Berlin"

DESCRIPTION

"A MIB to monitor Raspberry PIs"

REVISION "202005060200Z"

DESCRIPTION

"Version 1."

::= { netSnmpPlaypen 42 }

The name raspiMIB complies with the above-mentioned rule that names start with a lowercase letter and must not contain hyphens. The additional parameters are all necessary and have the following meanings:

-

LAST-UPDATEDindicates when the MIB was last updated. -

ORGANIZATIONindicates the organization or company to which the authors belong. -

CONTACT-INFOprovides contact information for the authors of the MIB. -

DESCRIPTIONis a textual description of the MIB (e.g., its purpose). -

REVISIONandDESCRIPTIONalways occur in pairs and describe a specific revision of the MIB. Changes to the MIB should always be explained briefly inDESCRIPTIONand accompanied by a newREVISION, which is also reflected inLAST-UPDATED.

The example assigns the value 42 to the name netSnmpPlaypen. If you think this looks like another OID, you are right. This name is defined in NET-SNMP MIB, again with reference to an existing name. If this chain is resolved recursively (e.g., using

$ snmptranslate -On NET-SNMP-MIB::netSnmpPlaypen

the OID .1.3.6.1.4.1.8072.9999.9999 is returned. The definition in Listing 4 appends the number 42, so in the end, the MIB defines raspiMIB as .1.3.6.1.4.1.8072.9999.9999.42.

Maybe you're now assuming that, thanks to this definition, all further definitions of the MIB are automatically created below this OID, but this is by no means the case. On the one hand, the definitions must explicitly refer to raspiMIB or other definitions. On the other hand, it is usually the case, but by no means the law, that they must refer to the names defined within the sub tree defined through the MODULE-IDENTITY macro.

The question remains why raspiMIB was defined below netSnmpPlaypen. Life is easy if you are developing a MIB in an organization for which IANA has assigned a separate sub-tree below enterprises and where you can apply for a corresponding attachment point internally. Even in this case, however, it might be useful initially to use the netSnmpPlaypen sub-tree, which is explicitly provided by the Net-SNMP project for your own experiments.

If your MIB is to be used within your organization only, you might be inclined to use any OID you like; after all, nobody outside the organization would be concerned. However, this hack can turn around and bite you if OID collisions occur because you have other MIBs in use. Such a choice should therefore be made only after careful consideration.

Tree and Leaf Care

So far, only the trunk of your own sub-tree has been defined. Some initial branches will now be added with the OBJECT IDENTIFIER keyword. The code in Listing 5 defines a raspiMIBObjects branch below raspiMIB, and below that in turn a raspiMIBScalars branch.

Listing 5: Initial Branches

-- MIB root nodes

raspiMIBObjects OBJECT IDENTIFIER ::= { raspiMIB 1 }

raspiMIBScalars OBJECT IDENTIFIER ::= { raspiMIBObjects 1 }

By the way, branches cannot be the subject of an IMPORTS statement. If you want to import all the objects in a branch, you have to list them explicitly and individually.

Next up, the OBJECT-TYPE macro in Listing 6 defines a managed object below raspiMIBScalars with the name socTemp and the data type Integer32 (i.e., a 32-bit integer). The object is supported in the current revision of the MIB (STATUS current) and can only be read, but not set, through SNMP (MAX-ACCESS read-only). By the way, in later snmpget queries, it is important always to append a .0 to scalar managed objects.

Listing 6: Managed Object

-- Scalars

socTemp OBJECT TYPE

SYNTAX Integer32

MAX-ACCESS read-only

STATUS current

DESCRIPTION

"The current temperature of Broadcom SoC multiplied by 1000."

::= { raspiMIBScalars 1 }

If you study Table 2 carefully, you will notice that it does not list a data type for floating point values. ASN.1 itself does not support a native Float type, and a standard for encoding floating point numbers has not been established. However, the problem can usually be avoided by transmitting a value multiplied by 10 – for example, 359 instead of 35.9. MIB authors should always describe such conventions in an object's DESCRIPTION.

Tabelle 2: SMIv2 Common Scalar Data Types

|

Type |

Short Description |

Defined in MIB |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Positive 32-bit counter value |

|

|

|

Positive 64-bit counter value |

|

|

|

ASCII-String from 0 to 255 characters in length |

|

|

|

Positive 32-bit measured value |

|

|

|

Positive or negative 32-bit integer |

|

|

|

IPv4 address |

|

|

|

Define a new sub-branch |

|

|

|

Positive 32-bit integer |

|

|

|

Positive 32-bit time value |

|

The example MIB is now complete; however, it makes sense to use the smilint tool from the smitools package first to check the MIB file passed in as a command line argument for conformity with the SMIv2 specifications from RFCs 2578 to 2580. The -l parameter modifies the strictness of the check. At the recommended level of 4, it is bound to find something:

$ smilint -l4 RASPI-MIB.txt RASPIMIB.TXT:36: warning: node 'socTemp' must be contained in at least one conformance group

The Conformance Statements specified in RFC 2578 take into account that the MIB designer can specify features in a MIB that not necessarily every implementation will use. For this reason, two macros allow the definition of groups of entities that can be implemented either all together or not at all: OBJECT-GROUP for related managed objects and NOTIFICATION-GROUP for related notifications. Several of these groups can then be grouped together with the MODULE-CAPABABILITIES macro and define degrees of implementation that a specific implementation can claim for itself.

To satisfy smilint, however, it is sufficient to define a suitable OBJECT-GROUP, which is done here in separate sub-branches for the sake of clarity (Listing 7). Listing 8 shows the completed MIB, which we now yet have to implement.

Listing 7: OBJECT-GROUP Definition

raspiMIBConformance OBJECT IDENTIFIER ::= { raspiMIB 2 }

-- Conformance

raspiMIBGroups OBJECT IDENTIFIER ::= { raspiMIBConformance 1 }

raspiMIBScalarsGroup OBJECT-GROUP

OBJECTS {

socTemp

}

STATUS current

DESCRIPTION

"Scalar managed objects from RASPI-MIB."

::= { raspiMIBGroups 1 }

Listing 8: RASPI-MIB.txt

RASPI-MIB DEFINITIONS ::= BEGIN

-----------------------------------------------------------

-- RASPI-MIB for monitoring different values of the Rasp Pi

-----------------------------------------------------------

-- Imports

IMPORTS

MODULE-IDENTITY, OBJECT-TYPE, Integer32

FROM SNMPv2-SMI

OBJECT-GROUP

FROM SNMPv2-CONF

netSnmpPlaypen

FROM NET-SNMP-MIB;

raspiMIB MODULE IDENTITY

LAST-UPDATED "202005060200Z"

ORGANIZATION "None"

CONTACT-INFO

"Editor:

Attentive reader

Raspberry Pi-Way 42

10487 Berlin"

DESCRIPTION

"A MIB to watch over Raspberry Pis"

REVISION "202005060200Z"

DESCRIPTION

"Version 1."

::= { netSnmpPlaypen 42 }

-- MIB root nodes

raspiMIBObjects OBJECT IDENTIFIER ::= { raspiMIB 1 }

raspiMIBConformance OBJECT IDENTIFIER ::= { raspiMIB 2 }

raspiMIBScalars OBJECT IDENTIFIER ::= { raspiMIBObjects 1 }

-- Scalars

socTemp OBJECT TYPE

SYNTAX Integer32

MAX-ACCESS read-only

STATUS current

DESCRIPTION

"The current temperature of Broadcom SoC multiplied by 1000."

::= { raspiMIBScalars 1 }

-- Conformance

raspiMIBGroups OBJECT IDENTIFIER ::= { raspiMIBConformance 1 }

raspiMIBScalarsGroup OBJECT-GROUP

OBJECTS {

socTemp

}

STATUS current

DESCRIPTION

"Scalar managed objects from the RASPI-MIB."

::= { raspiMIBGroups 1 }

END

From Agent to Agent

The interface through which snmpd will be contacted by the yet-to-be-written implementation is the Agent Extensibility (AgentX) protocol standardized in RFC 2741 [4]. Other extension mechanisms beyond extend exist in the form of dynamically loadable modules, such as pass_persist and the SMUX (SNMP multiplexing) protocol; however, AgentX offers more possibilities with loose coupling, which is advantageous from a security perspective.

In AgentX jargon, snmpd is the master agent, of which there is always exactly one, and to which multiple independently running processes, named subagents, can connect. After the connection is established, a subagent declares itself responsible for certain sub-trees of the MIB tree and their implementation. The master agent is the only agent to talk SNMP but knows nothing about custom MIBs and their implementation. With subagents, it is exactly the opposite.

To enable AgentX support in snmpd, you just need an extra master agentx line in the /etc/snmp/snmpd.conf file. By default, the connection between snmpd and the subagents uses the /var/agentx/master Unix Domain Socket, so from this perspective, AgentX is simply more or less an Interprocess Communication (IPC) mechanism. Technically, it would also be possible to configure a TCP socket; however, because AgentX does not provide any authentication mechanisms between the master agent and subagents and accepts any subagent, such a configuration would have to be accompanied by security measures such as firewalls.

Fortunately, Net-SNMP not only comes with snmpd, but also offers APIs and libraries, which the master agent itself uses too. For developers proficient in the C programming language, several tutorials [5] on the Net-SNMP website describe the development of a MIB module – for example, as a subagent. The mib2c tool includes a scaffolding tool, which takes a MIB as input and, after answering a few implementation questions, generates a detailed commented basic framework of C source code, with which you can push forward your MIB implementation.

However not everyone is proficient in C. For scenarios in which you want to integrate external information sources into your MIB, and at the same time achieve fast and yet sufficiently sophisticated results, common script languages are particularly useful. Net-SNMP comes with its own Perl module, but currently one particular lingua franca is certainly Python, for which resources looked a little scarce until 2013. With the Python module included with Net-SNMP, which consists of 2,500 lines of C code, you could implement SNMP clients but not agents. SourceForge, on the other hand, had a Python AgentX module [6], but it hasn't been maintained since 2010 and has several deficits.

For this reason, I decided to develop my own open source Python module, python-netsnmpagent [7]. Written in Python, it uses the Ctypes module provided with Python to access the C API of the Net-SNMP libnetsnmpagent.so and libnetsnmphelpers.so libraries and abstracts them for the Python programmer behind a netsnmpAgent class (and other classes for common data types) that can be used with just a few lines of code.

In the meantime, another Python module, pyagentx [8], appeared on GitHub, but it tries to implement the complete AgentX protocol on its own and has not been maintained since 2015. The python-netsnmpAgent module, on the other hand, saw its last changes in 2019 but still works on older enterprise distributions such as SLES 11 (Python 2.7, Net-SNMP 5.4.x), as well as on more recent systems with Python 3.5 or newer and Net-SNMP 5.7.x/5.8. For some distributions, such as SUSE, there are ready-made packages, but not for Debian and Raspbian, for which Python developers will need to install the module – possibly within a virtual environment – with Python's own Pip package manager:

$ apt-get install --no-install-recommends python3-pip $ pip3 install netsnmpagent

Listing 9 shows an initial version of a subagent for this example. After importing the netsnmpagent module, it creates an instance of the netsnmpAgent class that serves as a central hub for connecting to snmpd and managing objects. It expects a parameter with a descriptive name for the agent and, in this example, the path to your MIB. By explicitly specifying the MIB, you can experiment with RASPI-MIB.txt without having to install it globally on the system in /usr/share/snmp/mibs/.

Listing 9: raspiagent.py Structure

#!/usr/bin/python3

import os

import netsnmpagent

import sys

try:

agent = netsnmpagent.netsnmpAgent(

AgentName = "RaspiAgent",

MIBFiles = [

os.path.abspath(os.path.dirname(sys.argv[0]) +

"/RASPI-MIB.txt"

]

)

agent.start()

while True:

agent.check_and_process()

except netsnmpagent.netsnmpAgentException as e:

print(e)

sys.exit(1)

Calling the start() class method establishes the connection to snmpd. Afterward, the check_and_process() method is called repeatedly in an infinite loop, waiting for requests from the master agent and processing them. So far, however, the code still lacks any reference to the managed object socTemp.

Now add the code

socTemp = agent.Integer32( oidstr = "RASPI-MIB::socTemp" writable = False )

in front of the agent.start() line of Listing 9. The agent object provides factory methods, named after common SMIv2 data types, that return a new instance of a class with the same name, Integer32 in this case. In terms of parameters, you will always need to specify oidstr, which specifies the OID under which the given object instance is to be registered. The optional writable parameter specifies whether the instance can be changed by snmpset. The most important method provided by these classes is update(), to update the value of the managed object.

Start raspiagent.py in a console window with root privileges, and in a second console execute the command

$ snmpget -M+. -v2c -c rpitesting localhost RASPI-MIB::socTemp.0RASPI-MIB::socTemp.0 = INTEGER: 0

in the directory in which RASPI-MIB.txt and raspiagent.py reside.

However, the command always returns the value 0, because the temperature query has not yet been implemented. The code in Listing 10 adds this query. The command is the same as in the extend example, but further processing of the output is done with native Python tools. A successive execution of snmpget will now return the current temperature (multiplied by 1,000), as before with extend:

$ snmpget -M+. -v2c -c rpitesting localhost RASPI-MIB::socTemp.0 RASPI-MIB::socTemp.0 = INTEGER: 40622

Listing 10: Updating the socTemp Value

while True:

line = open("/sys/class/thermal/thermal_zone0/temp").readline()

socTemp.update(int(line))

agent.check_and_process()

The example shown here only implements a single managed object and, being Integer32, a rather simple one on top. Further examples of other scalar data types and tables can be found in the netsnmpagent archive available from the Python Package Index (PyPI) repository and the GitHub repository [9] in the form of simple_agent.py in the examples/ subdirectory.

You will also find a solution for another common problem there: In the case of raspiagent.py, you will notice a short wait before snmpwalk returns a value for socTemp. The agent performs its two main tasks of gathering and sharing information, one after the other, and calls vcgencmd for each request, which takes a little while. The solution is to decouple the two tasks, as demonstrated by threading_agent.py (also in the examples/ subdirectory), which uses threads.

Conclusions

Once you have familiarized yourself with the formal rules and the available data types and macros, writing a MIB is relatively easy. Now that python-netsnmpagent is available to implement the MIB, sys admins and developers can focus on integrating additional information sources into an existing SNMP monitoring setup.