DiffServ service classes for network QoS

Service Quality

Until a few years ago, the only critical factor on most networks was to transfer data as quickly and securely as possible between endpoints. Computers and network components on the LAN and WAN have been optimized for this purpose. However, this model is useless for Voice or Video over IP (VoIP), because both require low latency and guaranteed constant transmission rates from the network. Both packet loss and jitter can significantly affect the quality of voice transmission delivered to the end user. The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) has defined various quality of service (QoS) models for an IP network: best effort, IntServ (integrated services), and DiffServ (differentiated services).

QoS Models

The Internet uses the best-effort model, which offers minimal QoS assurance. For business networks, this model also applies if no QoS policies have been configured or the infrastructure does not support QoS. With the best-effort model, there is no guarantee that the packets will be delivered. Additionally, all packets have the same priority and are therefore treated identically. Packets from a VoIP stream are therefore processed with the same priority as those from an email session. Unfortunately, many companies that use VoIP still use the best-effort model because the infrastructure is not properly configured or QoS is simply not supported.

The IntServ model reserves bandwidth in the relevant network path, which guarantees the necessary bandwidth for mission-critical applications from end to end. IntServ uses signals for the QoS model: The end host signals the network's QoS requirements. Each individual communication stream has to request resources from the network. Edge routers use the Resource Reservation Protocol (RSVP) to signal that the appropriate bandwidth should be reserved for each flow on the network. One major drawback of the IntServ model is that each device in the path a packet takes must be fully compatible with RSVP, including routers, servers, personal computers (PCs), and other equipment.

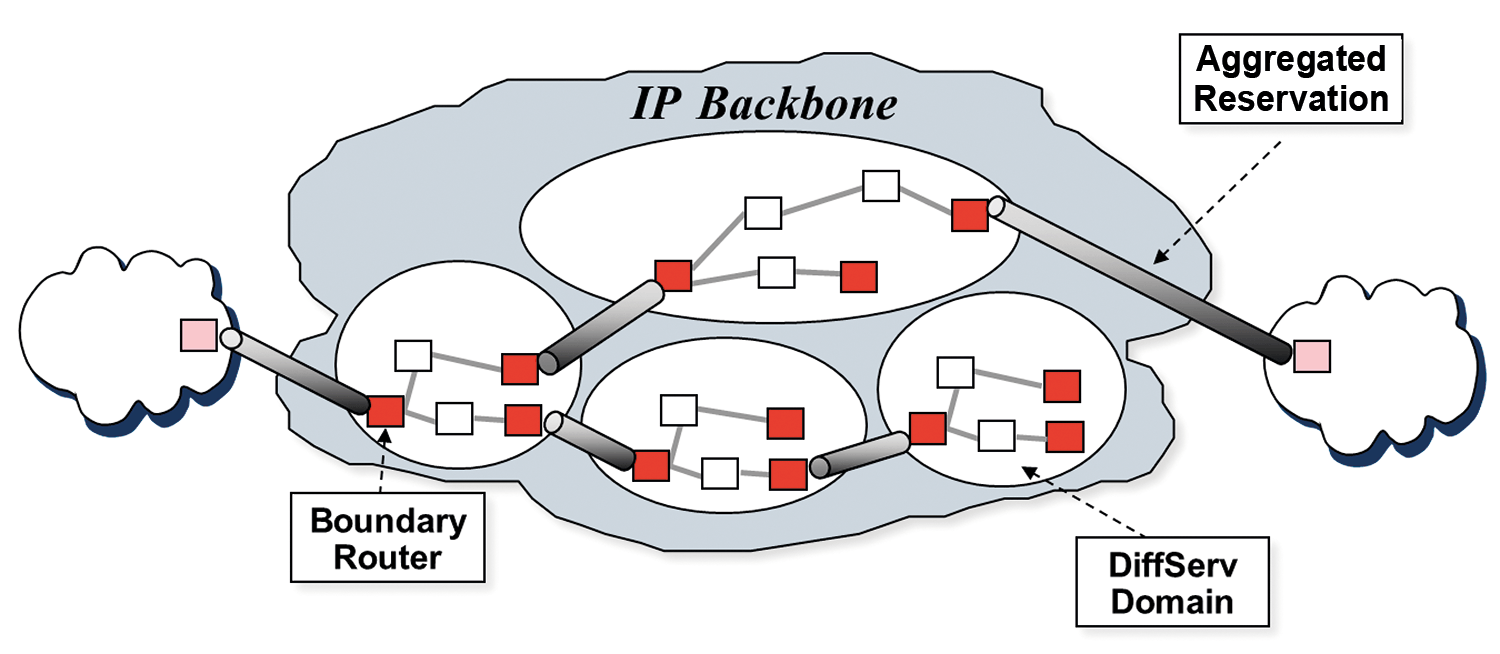

DiffServ service classes provide the necessary traffic characteristics to the various applications on an end-to-end basis. RFC 4594 defines 12 service classes: two for network operation and administration and 10 for applications and services.

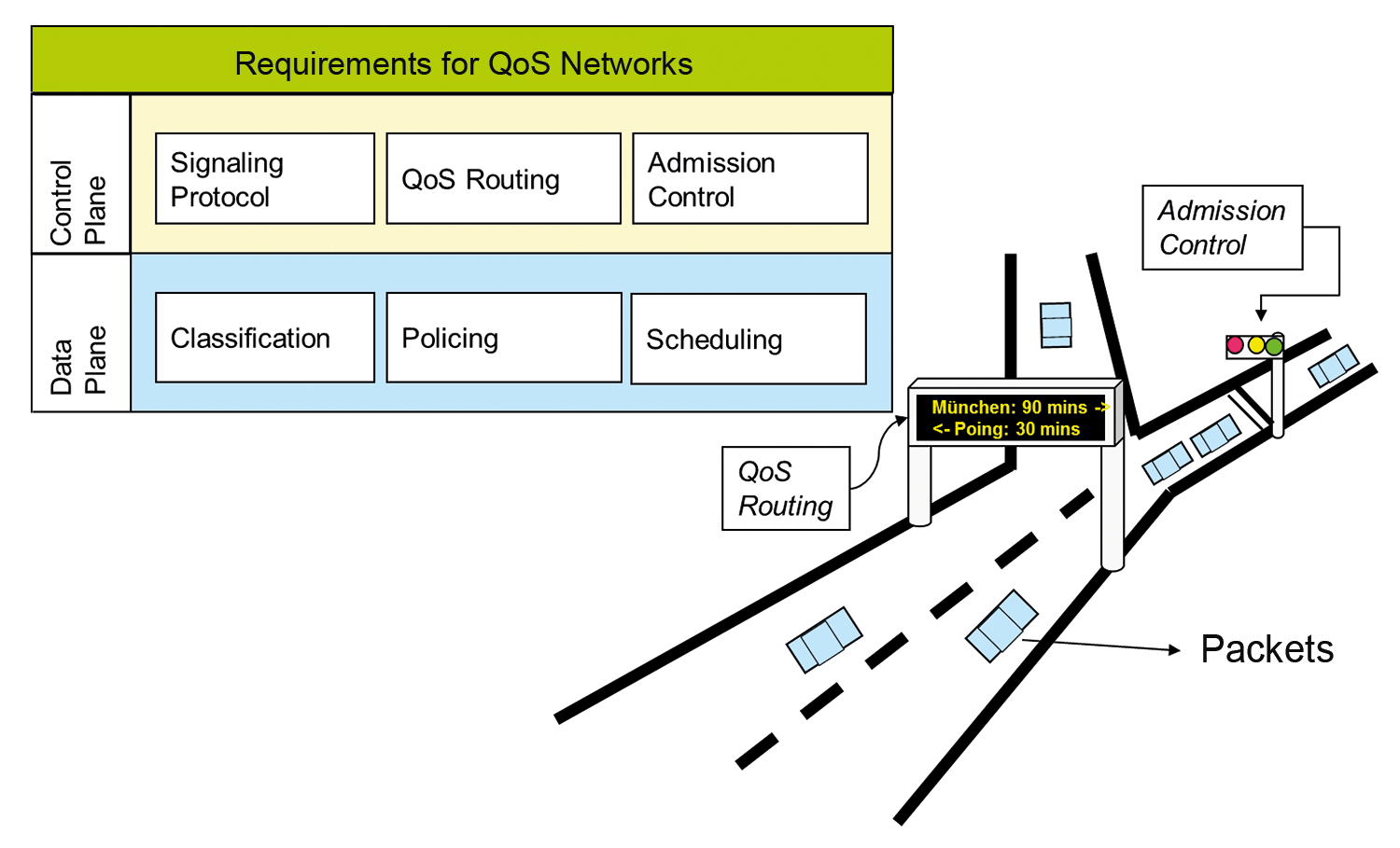

Service Class Mechanisms

A service class means a volume of traffic that imposes specific requirements (in terms of delay, loss, and jitter) on the network. Conceptually, a service class refers to applications with similar characteristics and performance requirements. The service classes are defined in a differentiated services (DS) domain but can also be implemented across multiple DS domains.

A service class defines the required characteristics of a traffic aggregate that is computed from the use of certain per-hop behaviors (PHBs), as defined in RFC 2474. The handling of a traffic aggregate within a domain (per-domain behavior) can be defined according to RFC 3086. Some mechanisms are available to implement the service classes, which I discuss in more detail later.

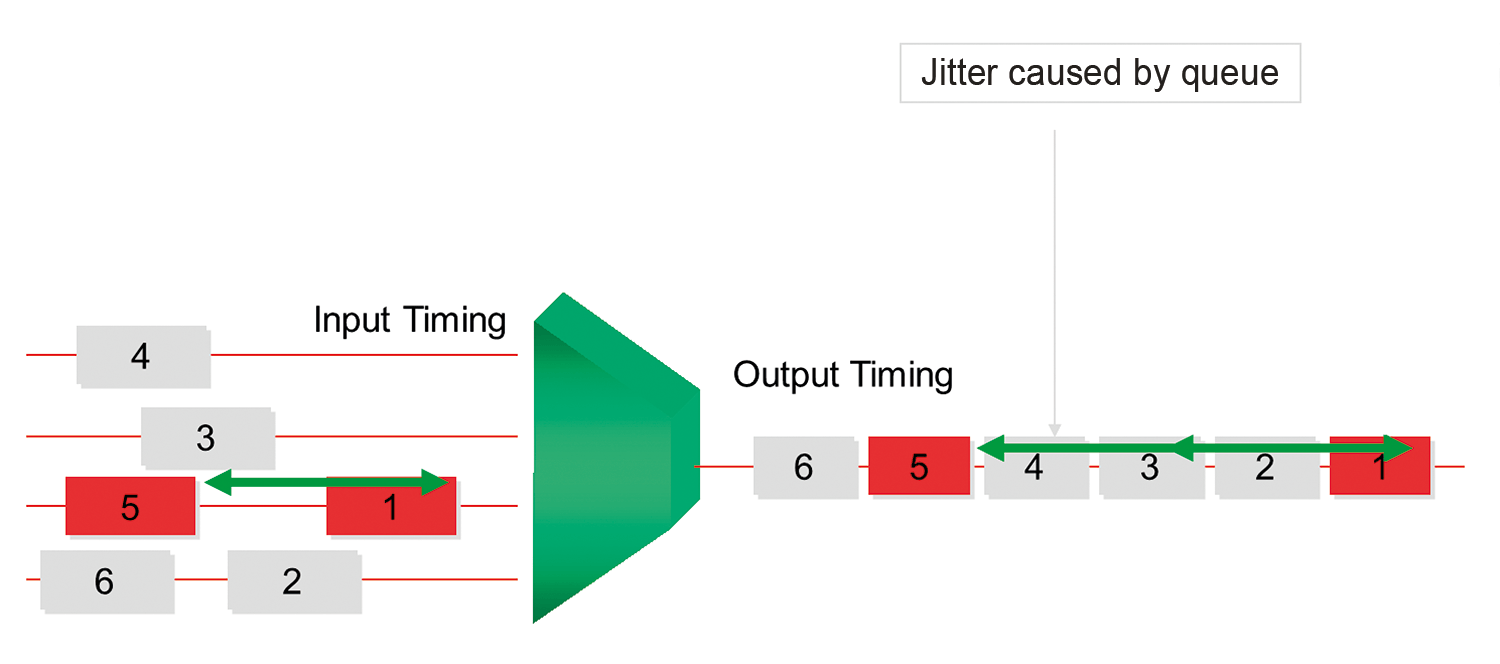

In queuing, a queue is formed if more requests are sent to a system per time unit than the system can process in the same time. The data packets to be transferred are delayed while being buffered in a queue because they are not forwarded in a timely manner as a consequence of insufficient bandwidth or low priority.

Priority queuing is a combination of a series of queues and a scheduler that empties the queues in order of priority. The scheduler checks the queue with the highest priority and forwards a packet stored therein for processing. Next, the scheduler checks the queue with the next lowest priority and so on. In a priority queue system, a packet in the queue with the highest priority experiences a predictable delay.

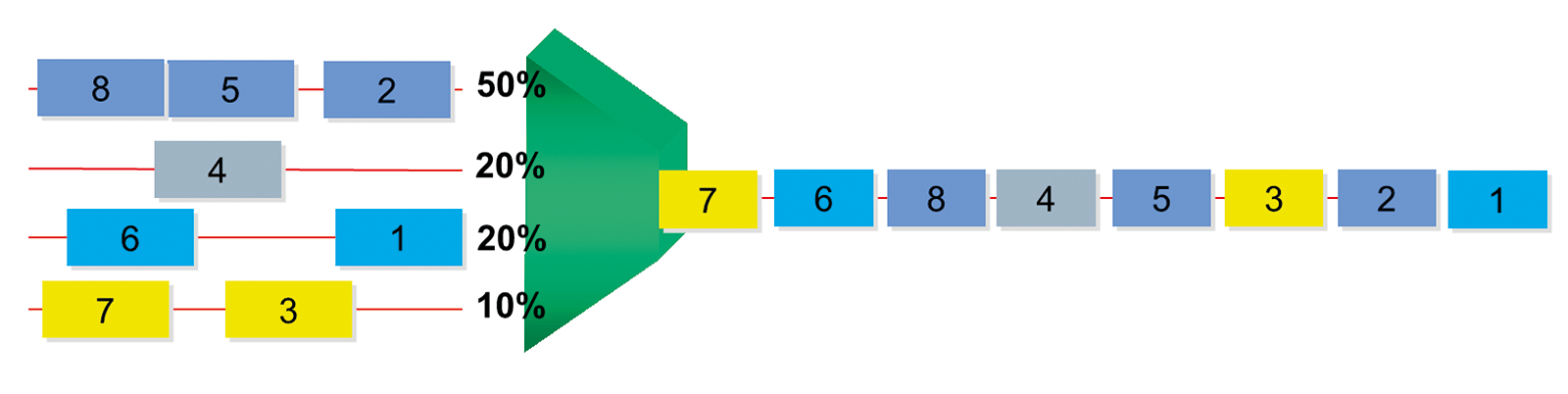

Rate queuing, or the rate-based queue system, comprises a combination of queues and a scheduler that empties each queue at a certain rate. In a rate-based queuing system, such as Weighted Fair Queuing (WFQ) or Weighted Round Robin (WRR), the delay experienced by a packet in a particular queue depends on the occupancy of the queues with which it competes.

Active Queue Management (AQM) is a management method for dropping and flagging packets in a queue. An example of such a procedure is Random Early Detection (RED). This mechanism pre-emptively drops packets before the buffer becomes completely full. A queue is assigned a minimum threshold, which is the average queue size below which no packets will be dropped, and a maximum threshold, which is the average queue size above which all packets will be dropped.

The queue algorithm ensures that the queues are only ever filled to an average extent (depth), which varies between the minimum and maximum thresholds. If the average queue depth is below the minimum threshold, all packets are queued up. If the average queue depth approaches the maximum threshold value, the probablility an incoming packet is dropped increases. If the average queue depth is between the thresholds, a randomly selected subset of the incoming traffic is flagged or dropped.

A variation of this algorithm is used in Assured Forwarding PHB (RFC 2597). In this case, several differentiated services codepoint (DSCP) markers are mixed in a common queue. Different minima and maxima are configured separately for the different DSCP values, so that traffic exceeding a specified rate when entering the queue is more likely to be dropped or flagged than traffic that is within the agreed upon rate.

In traffic conditioning, incoming traffic is measured in line with a policy on the access router to the network and dropped or flagged, ensuring that the network flows are already formed at the edge of the network (Figure 1). For this reason, these processing methods are known as "traffic conditioners." The following traffic conditioners can be used to provide differentiated services:

- Class Selector (CS) PHB: A single token bucket meter provides one data rate plus burst size control.

- Expedited Forwarding (EF) PHB: A single token bucket meter controls the data rate and burst sizes.

- Assured Forwarding (AF) PHB: Typically, two token bucket meters are configured to control behavior as per a two-rate three-color marker (RFC 2698) or single-rate three-color marker (RFC 2697). The two- and three-color markers are used to enforce two data rates, whereas the single-rate three-color marker is used to enforce a fixed rate with two burst lengths.

The DSCPs have values from 0 to 63 that are inserted into the IP header, thus marking the corresponding traffic class. Currently, half of the DSCP values are reserved for standardized services. The other half are available for local definitions. The described mechanisms are used for specific features for forwarding different types of traffic depending on the requirements of the application. DSCPs are only used for classification, not prioritization, which means that a higher numerical value does not necessarily correspond to a preferred treatment. Instead, a DSCP relates to a forwarding behavior (PHB) that specifies how to handle a packet.

Understanding Forwarding Behavior

Differentiated services – as the sum total of all DSCPs – provide a general architecture for the implementation of a variety of services. For practical purposes, three basic forwarding behaviors are defined, the first of which is default forwarding (DF). The forwarding behavior for each traffic class is described in RFCs 2474 and 2309. The network operator promises its users that incoming transmission requests will be handled as quickly as possible and to the best of its ability within the limits of the resources available and minimal QoS assurance. On packet-switching networks, best effort means forwarding all incoming packets as long as free transmission capacity still exists on the network. Error-free and complete transmission are not guaranteed. If the capacity is fully utilized at a certain point in the transmission path, congestion inevitably occurs.

The second behavior, Assured Forwarding (AF) according to RFC 2597, offers four classes of forwarding behavior that you can specify for the marker. Table 1 shows the classes, the three drop priority levels for each class, and the recommended values (decimal and binary) of AF codepoints.

Tabelle 1: Assured Forwarding Codepoints

|

Priority Level |

Class 1 |

Class 2 |

Class 3 |

Class 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Low drop |

AF11 = 10 (001010) |

AF21 = 18 (010010) |

AF31 = 26 (011010) |

AF41 = 34 (100010) |

|

Medium drop |

AF12 = 12 (001100) |

AF22 = 20 (010100) |

AF32 = 28 (011100) |

AF42 = 36 (100100) |

|

High drop |

AF13 = 14 (001110) |

AF23 = 22 (010110) |

AF33 = 30 (011110) |

AF43 = 38 (100110) |

Finally, expedited forwarding (EF) as per RFC 3246 guarantees that packets with EF codepoint 46 receive the best handling available on the network. Thus, packets with codepoint 46 are guaranteed to receive preferential treatment from all DiffServ routers on their way to their destination.

Differentiation of Services

Differentiation of services is based on the various service classes available on the network to provide the necessary performance for applications while allowing several applications with similar traffic characteristics and performance requirements to be grouped together in the same service class (Figure 2). The IETF chose to divide services into two groups: network control traffic and user traffic.

To enable differentiation of services, different service classes are defined in each group: two for the Network Control traffic group for routing and network control functions and OAM for network operations, administration, and management functions.

The user traffic group has the following services:

- The Telephony service class is suitable for applications that rely on delay changes being very low and provide constant transmission speeds.

- The Signaling service class is best suited for peer-to-peer and client-server signaling functions that use protocols such as Session Initiation Protocol (SIP), H.323, H.248, and the Media Gateway Control Protocol (MGCP).

- The Multimedia Conferencing service class supports applications that require very low delay and can change the encoding rate (rate-adaptive), such as H.323/V2 and newer video conferencing services.

- The Real-Time Interactive service class is intended for interactive non-elastic applications with variable data rates that require low jitter and loss and very low delay.

- The Multimedia Streaming service class is used for elastic streaming applications with a variable rate, wherein a human is waiting for data output and in which the application is able to react to packet loss by reducing the transmission rate.

- The Broadcast Video service class is suitable for non-elastic streaming applications that have constant or variable data rates and also require low jitter and packet loss rate (e.g., video surveillance).

- The Low-Latency Data service class is suitable for applications in which a human interacts with a PC.

- The High-Throughput Data service class is intended for store-and-forward applications (e.g., FTP).

- The Standard service class is intended for normal (non-priority) traffic and is referred to as the best-effort class.

- The Low-Priority Data service class is intended for traffic with no need for bandwidth assurance.

User Service Class Categories

The 10 user service classes can be grouped into a small number of application categories. However, for some application categories, it was necessary to define more than one service class to allow for differentiation of services within each category.

The Application Control category is intended for controlling applications or user endpoints. Protocols that use this service class are the SIP or H.248 for IP telephony services or the Internet Group Management Protocol (IGMP) for multicast control. The main difference is the administrative control and management of the affected data streams, because the protocols of this class tend to be bound to the media stream they signal and control.

Because of the large number of media-oriented services on IP networks, five service classes in the Media-Oriented category are defined: Telephony, Real-Time Interactive, Multimedia Conferencing (for video conferencing solutions that are able to reduce their transmission rates after detecting a traffic bottleneck), Broadcast Video, and Multimedia Streaming. The latter content is usually stored before transmission and buffered at the receiving end before being played back. The buffer is sufficiently large to take into account any transmission variation that may occur in the network.

The Data category comprises Low-Latency Data for applications and services that require low delay or latency for bursty but short-lived data flows, High-Throughput Data for applications and services characterized by good throughput for long-lasting burst-like data streams, and Low-Priority Data for applications or services that tolerate short or long interruptions in packet flow.

All undifferentiated traffic on the network falls under the best-effort umbrella and is classified in the Standard service class. If a packet is marked with a DSCP value that is not supported on the network, it should be forwarded by the Standard service class.

Table 2 shows the traffic behavior for the different traffic flows. The Characteristics column defines the desired characteristics and profiles of the respective traffic flows, as well as their tolerance in the areas of packet loss, delay, and jitter. The performance parameters are based on ITU-T Recommendations Y.1541 and Y.1540 [1]. The DSCP Mapping column provides a summary of the DiffServ QoS mechanisms to be used for the defined service classes.

Tabelle 2: Traffic Behavior and QoS Mechanisms

|

Characteristics |

DSCP Mapping |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tolerance |

||||||||||

|

Service Class |

Traffic |

Package Loss |

Delay |

Jitter (a) |

DSCP |

Condition on DS edge (b) |

PHB Used |

Queuing |

AQM |

|

|

Network Control |

Packets of variable size, mostly inelastic short messages, but traffic can also contain bursts. |

Low |

Low |

Low |

CS6 |

Guaranteed services |

RFC 2474 |

Rate |

Yes |

|

|

Telephony |

Short packets of fixed size, constant data rate, inelastic and low-performance traffic streams. |

Extremely low |

Extremely low |

Extremely low |

EF |

Policy based on sr+bs |

RFC 3246 |

Priority |

No |

|

|

Signaling |

Packets of variable size, some of which are short-term, burst-like data streams. |

Low |

Low |

Low |

CS5 |

Policy based on sr+bs |

RFC 2474 |

Rate |

No |

|

|

Multimedia Conferencing |

Packets of variable size, constant transmission interval, rate-adaptive, react critically to losses |

Low to medium |

Low |

Extremely low |

AF41, AF42, AF43 |

Use of bivalent, three-color markers (RFC 2698) |

RFC 2597 |

Rate |

via DHCP |

|

|

Real-Time Interactive |

RTP/UDP streams, inelastic, mostly variable data rate. |

Low |

Extremely low |

Low |

CS4 |

Policy based on sr+bs |

RFC 2474 |

Rate |

No |

|

|

Multimedia Streaming |

Packets with variable size, elastic with variable data rate. |

Low to medium |

Medium |

Yes |

AF31, AF32, AF33 |

Use of bivalent, three-color markers (RFC 2698) |

RFC 2597 |

Rate |

via DHCP |

|

|

Broadcast Video |

Constant and variable data rates, non-elastic and non-burst data streams. |

Extremely low |

Low |

Low |

CS3 |

Policy based on sr+bs |

RFC 2474 |

Rate |

No |

|

|

Low-Latency Data |

Variable data rate, burst-like, short-lived, elastic data streams. |

Low |

Low to medium |

Yes |

AF21, AF22, AF23 |

Use of monovalent, three-color markers (RFC 2697) |

RFC 2597 |

Rate |

via DHCP |

|

|

OAM |

Variable size packets, elastic and inelastic data streams. |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

CS2 |

Policy based on sr+bs |

RFC 2474 |

Rate |

Yes |

|

|

High-Throughput Data |

Variable data rate, burst-like, long-lasting, elastic data streams. |

Low |

Low to medium |

Yes |

AF11, AF12, AF13 |

Use of bivalent, three-color markers (RFC 2698) |

RFC 2597 |

Rate |

via DHCP |

|

|

Standard |

Contains all traffic characteristics in varying proportions. |

Unspecified |

DF |

Not applicable |

RFC 2474 |

Rate |

Yes |

|||

|

Low-Priority Data |

Elastic non-real-time currents. |

High |

High |

Yes |

CS1 |

Not applicable |

RFC 3662 |

Rate |

Yes |

|

|

(a) "Yes" in the Jitter column means that the data is buffered at the endpoint and that a moderate network-induced variation in delay will not affect the application. |

||||||||||

|

(b) sr+bs provides a control mechanism that offers a uniform data rate with control of the burst sizes. |

Service Classes in Practice

Now that the theoretical foundations for the use of the service classes has been presented and the theory behind the 12 DiffServ service classes that provide QoS on the network for demanding modern applications has been discussed, the next step is to use these classes to control the data streams on the network and to ensure optimal quality for video and voice over IP. In the next sections, I look into practical implementations on the network for telephony, video communication, and controlling data streams.

The integration of QoS mechanisms usually starts with three or four service classes on most networks; more classes are then added later as needed. I will look at this integration with reference to two examples.

In the first case, an administrator wants to provide different performance levels (i.e., QoS) for the services to be transmitted, including reliable transport for VoIP services (comparable to the public telephone network), data services with low latency and guaranteed bandwidth, and support for current Internet services.

The admin fulfills these requirements by providing the following six service classes:

- The Network Control service class is responsible for routing and controlling traffic and ensures the reliable operation of the provider's network.

- The Standard service class is responsible for all data traffic (e.g., Internet services) and guarantees undifferentiated forwarding of data over the provider's network.

- The Telephony service class ensures the smooth transmission of VoIP traffic.

- The Signaling service class controls the VoIP service.

- The Low-Latency Data service classes guarantee a bandwidth-differentiated data service.

- The OAM service class ensures operation and management of the provider's network.

In a second example, a network administrator has to provide different features on the network. The requirements are:

- Reliable VoIP services

- Video conferencing services for selected conference rooms

- On-demand delivery of pre-recorded audio and video information to a large number of users

- Provision of a priority data transmission function

- Reduction of available bandwidth during peak hours for selected applications

- Availability of a normal IP service for all other applications and services

Admins meet these network requirements with the help of nine service classes: the six service classes used in the first example plus the Multimedia Conferencing service class for video conferences, the Multimedia Streaming service class for pre-recorded audio and video information, and the High-Throughput Data service class for mass data transport.

Service Classes for Network Control

Network control traffic refers to packet streams that are necessary for stable operation of the network and exchanging information between neighboring networks. Traffic between adjacent networks is transmitted via a shared peering point and is assessed against service-level agreements (SLAs). Network control traffic is usually different from the control data of the user application and is broken down into the Network Control and OAM service classes.

The Network Control service class is used to transfer packets between routers that need to exchange control (routing) information between nodes within the administrative domain and, via a peering point, between different administrative domains. The traffic transmitted in this service class must be forwarded in a timely manner, because this is fundamental to network operation.

You need to configure this class of service so that a minimum bandwidth is guaranteed for the traffic to ensure timely packet forwarding. The traffic characteristics of packet streams in this class of service are primarily the transmission of messages between routers and network servers, the predominant transmission of packets of variable size, and that normal traffic between users does not use this class of service.

The basic service of this class is based on an extended best-effort service with high-bandwidth assurance. Network Control can be used to transport both elastic and non-elastic data streams. You need to design the service so that AQM uses only CS6-tagged packets according to RFC 4594. If you define RED (according to RFC 2309) as the AQM algorithm, the minth threshold value specifies a target queue depth and the maxth threshold value defines the queue depth from which all data traffic is interrupted or Explicit Congestion Notification (ECN) marked.

The OAM class of service is for the following protocols: Simple Network Management (SNMP), Trivial File Transfer (TFTP), FTP, and Common Open Policy Service (COPS). These applications need low packet loss on the network but are relatively insensitive to delays. OAM should be configured so that the traffic has a minimum guaranteed bandwidth to ensure that packets are forwarded in a timely manner.

The OAM service class should be used for provisioning and configuring network elements, performance monitoring on the network, and all operational alerts on the network. Applications or IP endpoints need to tag their packets with the CS2 DSCP value up front. If the endpoint is not capable of doing this, the router that is topologically closest to the endpoint should handle Multifield (MF) classification (according to RFC 2475).

OAM is also based on an extended best-effort service with controlled data rates. The service needs to be designed such that CS2-tagged packet streams have sufficient bandwidth on the network, thus ensuring a high level of delivery reliability. If RED (according to RFC 2309) is used as the AQM algorithm, the minth threshold indicates a target queue depth and the maxth threshold indicates the queue depth above which all traffic is interrupted or ECN tagged.

Service Classes for Telephony and Video

User traffic is defined as the packet stream between different users and refers to the data traffic that is transmitted to or from terminal equipment. This is characterized by a very wide variety of applications and services. The first of these is the Telephony service class, which is intended for applications that transmit data in real time. It is also characterized by a very low delay, very low jitter, and very low packet loss for relatively constant data streams (Figure 3).

The Telephony service class needs to use the Expedited Forwarding (EF) PHB (according to RFC 3246) and should be configured to provide guaranteed forwarding resources so that all packets are forwarded quickly. Applications using this class of service include VoIP, data over IP such as modem or fax, T.38 fax over IP, connection emulation over IP, virtual lines, and IP virtual private network (VPN) services.

The Signaling service class supports delay-sensitive client-server applications (telephony) and peer-to-peer applications. This service class is designed for session control. Applications in this service class require a relatively fast response, because typically multiple messages are transmitted to control the sessions. You need to configure the signaling to respond quickly to intermittent and brief disturbances and to maintain the real-time nature of the data streams. Applications in this class of services include peer-to-peer IP telephony (e.g., SIP or H.323), peer-to-peer signaling for multimedia applications, the control function for peer-to-peer real-time streams, signaling for client-server IP telephony, control of IP television (IPTV) applications with protocols such as IGMP, and signaling of data flows between telephony call servers or soft switches with protocols such as SIP-T.

The Multimedia Conferencing service provides real-time services for rate-adaptive applications. Senders (sources) in this service class have the option of dynamically changing their transmission rates according to the feedback from the receiver. Typical video conferencing solutions negotiate the establishment of multimedia sessions with the SIP/H.323 protocol. When a user or endpoint starts a multimedia session, it is essential to check that the data rate of the new connection matches the available transmission resources.

Multimedia Conferencing needs to use the Assured Forwarding (AF) PHB and be configured to provide sufficient bandwidth for AF41, AF42, and AF43 packets to be forwarded securely. Typically interactive, time-sensitive, and business-critical applications require this class of service, including video conferencing applications, non-bursty data transfers between two application servers that require very low delay, and an IP VPN service that requires two data rates and a medium network delay that is slightly longer than the network propagation delay.

The Real-Time Interactive service class is available for variable data rate applications that require low loss and jitter and very low delay. Such services include, for example, a video conferencing application that is unable to change encoding rates or tag packets with different DSCP values. Typically, applications in this class of service are configured to negotiate the connection with a real-time transport (RTP)/User Datagram Protocol (UDP) control session. When a user or endpoint starts a real-time interactive session, it is important to check that the data rate of the new connection matches the transmission resources provided.

The service class uses the Class Selector (CS) PHB; it needs to provide a minimum bandwidth for CS4-tagged packets and guarantee that they are forwarded. Typical uses for this class of service are interactive games; video conferencing applications that do not require rate control or traffic content marking; IP VPN services that require a constant data rate and average network delay; and non-elastic, interactive, time-sensitive, and mission-critical applications that require very low delay.

The next class, Multimedia Streaming, enables near-real-time packet forwarding of elastic traffic sources that require a variable data rate and are not delay-sensitive. In general, multimedia streaming assumes that traffic is buffered at the source and destination. Therefore, this class of service is less sensitive to delay and jitter; it uses the Assured Forwarding (AF) PHB defined in RFC 2597. Applications that benefit from this class of service include buffered streaming audio and video (unicast), webcasts, and IP VPN services that support two data rates and are not sensitive to delay and jitter.

The Broadcast Video service class is recommended for applications requiring near-real-time packet forwarding with very low packet loss at a constant rate and non-elastic data sources at a variable rate. This service class assumes that the target endpoints have a de-jitter buffer, which is typically a two- to eight-video-frame buffer for video applications, which are therefore less sensitive to delay and jitter. This class of service uses the CS PHP and needs to be set up to provide high bandwidth for CS3-tagged packets and guarantee that they are forwarded. Applications that benefit from this class include video surveillance (unicast), video-on-demand (unicast), and streaming of live audio events (both unicast and multicast).

Service Classes for Data Streams

The Low-Latency Data service class is suitable for responsive, elastic data streams. It is typically used for client-server applications that have relatively fast response times and asymmetric bandwidth requirements. This communication mechanism is used, for example, when a user clicks on a hyperlink on a web page and thus loads a new web page.

This class of service is configured for good results with short-lived, real-time streams transmitted over TCP at variable data rates. The service class ensures that AF21, AF22, and AF23-tagged packet streams have a minimum network bandwidth to ensure high delivery reliability. Examples of applications that use low-latency data include client-server applications, Systems Network Architecture (SNA) terminals for hosting transactions, web-based transactions in e-commerce, or enterprise resource planning (ERP) applications.

The High-Throughput Data class is designed for elastic applications that require real-time packet transmission from the data source at a variable rate. These applications must be configured to provide good throughput for TCP data streams over a long period of time. This service class ensures the timely forwarding of AF11, AF12, and AF13-tagged packets. Typical applications in this environment are store and forward, file transfer, email, and VPN services that support two data rates (a fixed information rate and a higher data rate).

The Standard class of service is used for data streams that cannot be assigned to any other class of service and offers only best-effort forwarding behavior and a minimum bandwidth guarantee. The service class uses default forwarding PHB and is used by network services such as DNS, DHCP, BootP, and any undifferentiated packet streams that travel over the DiffServ-enabled network.

Last but not least, the Low-Priority Data service class serves applications that transmit according to the TCP protocol. This service class is specified in RFC 3662 and provides only a best-effort service without any bandwidth guarantees.

Conclusions

The prioritization procedures presented here ensure improvements in the transmission of data streams (Figure 4). However, some of the proposed potential solutions differ fundamentally or require the combination of individual partial solutions. No single solution offers a panacea for every network problem.

For this reason, when designing the network, first you need to make sure that the network bandwidth is available as a mandatory requirement. QoS is not a panacea for insufficient transmission capacity on the network. Adequate bandwidth helps reduce delays and packet loss. Second, you need to counteract connection saturation or overload in the transmission path with the appropriate queuing procedures, which ensures that high-priority traffic flows are transmitted, even if transport resources are overloaded.

Ultimately, you can only achieve quality through quality assurance (i.e., by using suitable metrics). Admins often check passive lines but wrongly assume that active components can be ignored. However, experience shows that big differences can exist between what the data sheet claims and the actual network component.