How graph databases work

Relationships

Typical relational databases map relations indirectly by means of joins, whereas graph databases map the same relations directly. One example of the use of a graph database involves the so-called Panama Papers. Tax fraud, money laundering, breaches of sanctions, and a number of other criminal offenses were levied against clients of the Panamanian offshore service provider Mossack Fonseca. In 2016, journalists associated with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) from 107 newspapers, television stations, and online media in 80 countries uncovered the crimes by jointly analyzing some 11.5 million leaked email messages, database entries, letters, fax documents, deeds of incorporation, loan agreements, bills, and bank statements with the help of a graph database.

Relations

Alice likes Bob who follows Carol and Dave on Twitter. Streetcar line 15 runs from Max-Weber-Platz via Giesing to Gr¸nwald. Mr. Huber is the superior of Mr. Meyer and Mrs. Schulze. Theresa liked the video that Mike recommended. Vehicle is the generic term for car, motorcycle, and truck. Modern man is related to early hominids and other species of great apes.

All these statements have one thing in common: They are about relations – about connections between people or things for which you could intuitively sketch something tree-like on a piece of paper. Such relationships are becoming more important in a world that is becoming increasingly networked, where everything is connected with everyone.

It is certainly no coincidence that relations are at the heart of the business ideas of corporations that are now among the most valuable and powerful in the world – Facebook and Google, for example. In the first case, it's about relationships between people who know each other; in the second, it's about relationships between websites that link to each other. The often-quoted page ranking is the measure of these connections. Networking is the common denominator between these models, and relations are its underpinnings. This is also true for countless other applications where relations play the main role, be it in purchase recommendations, dating portals, fraudulent transaction detection, genetics, logistics, and so on and so forth.

Of all data structures, one is particularly well suited to representing relationships – the graph. Graph databases, in turn, can store graphs, expand or shrink them, update and rearrange them, and answer questions about their content. Other developments have certainly attracted more public attention, but, out of the spotlight somewhat, the trend curve of the "graph database" search term on Google has been rising steadily for the past 10 years.

In parallel, a great variety of graph databases have emerged, including the originals like Neo4j [1], distributed databases like Titan [2], free databases like JanusGraph [3], proprietary databases like Amazon Neptune [4], and established relational or NoSQL databases that have added the ability to handle graphs. An example of the latter is the DataStax Enterprise Graph [5] database, which combines the open source Cassandra [6] database with the also free Apache TinkerPop [7] graph computing framework to create a successful product.

Today, graph databases are in production use in almost all industries in leading global corporations, including – to quote just a few names from customer lists – NASA, Walmart, Siemens, Google, Samsung, eBay, IBM, Airbnb, Novartis, Volvo, and many others. If you want to look into graph databases, a short crash course in graph theory will certainly do no harm (see the "Graph Theory" box).

In short, a finite sequence of the type node-edge-node-… is a path. If the starting point is equal to the end point, the path is closed; otherwise, it is open. A closed path with different vertices and edges is known as a circuit. A simple graph without circuits is a tree. Visiting each vertex and edge in a graph is a traversal; a tree traversal is a special case of the graph traversal.

A sample application of the paths concept can be found in project management, whose processes can be represented as a directed graph, in which the edges are usually weighted with a time duration. A route that contains the longest chain of interdependent steps determines the minimum project duration and is known as the critical path; the corresponding scheduling method is the critical path method (CPM). Any delays on this path have a direct effect on the overall project duration.

RDF and LPG

Graphs can represent many situations: computer networks, subway maps, organizational charts, flowcharts, molecular structures, decision paths, circuit paths, social networks, family trees, knowledge content, supply chains, and much more. Computer science uses several coding models, including the resource description framework (RDF) model [8] and the labeled property graph (LPG) model introduced by the Neo4j database.

The RDF model comes from the semantic web environment, which aims to enrich data with contextual information. RDF describes graphs as triples with the form subject-predicate-object. The first part of each triple is the subject node, followed by the predicate, which represents the edge and describes the nature of the relationship in more detail. At the end is the object, which can be a simple literal value. An example that could show a simplified section of a relationship network on Twitter might look like this:

Hans – follows – Werner

Werner – follows – Hans

Thomas – follows – Hans

In reality, however, the subject, predicate, and object in the RDF model are unique Unified Resource Identifiers (URIs), which are needed to mix information from different sources. (The universally known URLs are a special form of URI for the designation of Internet pages). The elements of an RDF triple, the URIs, are plain references – or simple literals in the case of some objects – that have no internal structure. One advantage is their uniqueness.

A bibliographic reference to the website http://www.example.org/index.html stating the author, date of creation, and language could look like Listing 1 in the RDF model. In the example, the URI http://purl.org/dc... conforms to the Dublin Core metadata standard.

Listing 1: RDF Triple Examples

<http://www.example.org/index.html> <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/creator> <http://www.example.org/staffid/94640> . <http://www.example.org/index.html> <http://www.example.org/terms/creation-date> "May 10, 2019" . <http://www.example.org/index.html> <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/language> "de" .

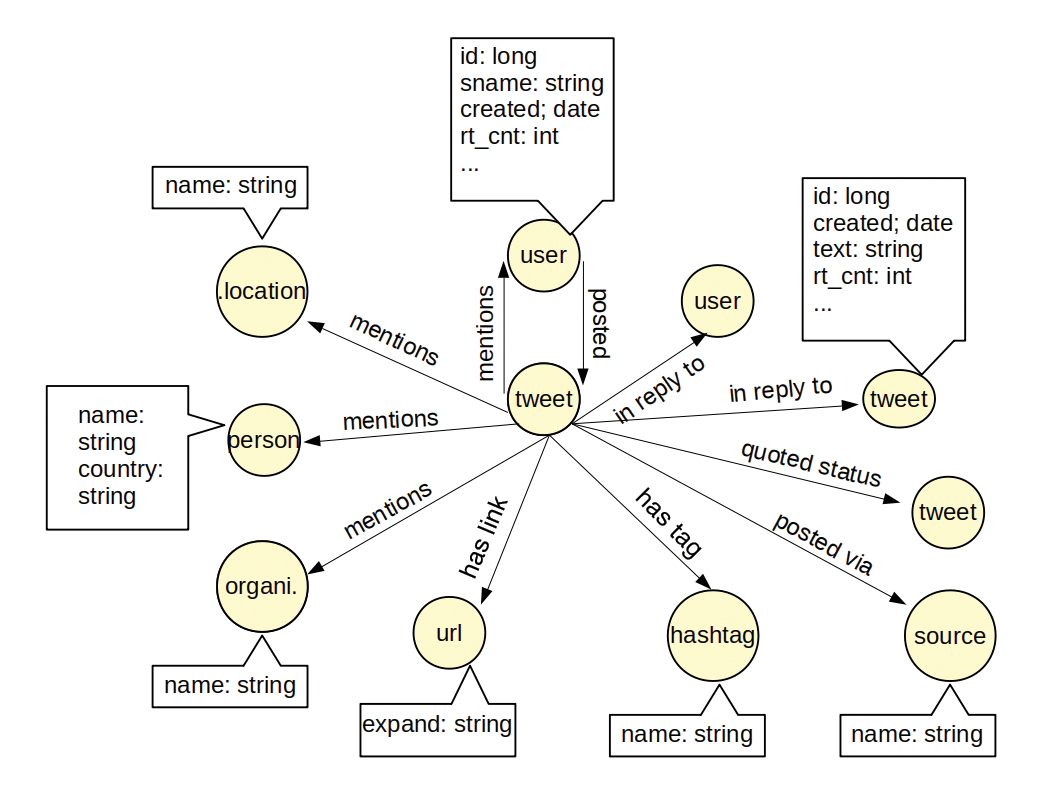

LPG is slightly different, in that the nodes and edges have an internal structure. Each node and edge is its own small key-value store that stores its attributes. Different types of nodes or edges can contain a different number of these key-value pairs. Because the attributes are not extra nodes, unlike the RDF model, the representation is more compact. Additionally, individual properties of relationships and multiple relationships of the same type between subject and object can be more easily mapped in LPG format. However, the meaning of the freely definable key-value pairs attached to the nodes and edges is not defined uniquely in the same way as in the RDF model with URIs. A sample of a schema for storing Twitter tweets in LPG would look something like Figure 3.

Graph Databases

Some graph databases use the RDF model and others use the LPG model. Additionally, databases can be distinguished according to whether they are native graph databases that use a storage engine designed specifically for graphs or non-native graph databases that serialize the graphs in some form and then store them with a proven relational or NoSQL storage engine. Both have advantages and disadvantages. For example, native databases are usually faster, whereas non-native databases rely on a long known and well understood and optimized technique.

Query languages are another distinguishing feature. Unlike the relational world, no single standard such as SQL has been established; rather, a number of different query languages have emerged, including the widely used Cypher, Gremlin (as used in this article), SPARQL, GraphQL, and others. Although graph databases are mainly used for online transaction processing (OLTP), graph compute engines process large batch jobs with graph data (online analytical processing, or OLAP).

Both techniques are best suited for scenarios in which the object is less about retrieving discrete facts than related things, or relationships. Anything that can be represented as a network or tree is a meaningful task for graph databases, which includes anything that has to do with finding patterns or hotspots in a network. Such cases can only be represented inefficiently and with poor performance in the relational model because the relationships have to be represented by joins and special tables and cannot have any special properties.

First Steps

The Gremlin Console is one easy way to experiment with a graph database. Gremlin is the query language for Apache TinkerPop, an abstraction layer for multiple graph databases and processors that uses the LPG model.

Gremlin supports declarative pattern matching, which means that what is described is the problem, not the how or the solution. It is also path-based, meaning that queries follow a chain of nodes. Among others, Neo4j, OrientDB, DataStax Enterprise, Hadoop, and Amazon Neptune can use the Gremlin query language – sometimes in parallel with other query languages, which sometimes (e.g., SPARQL) can also be translated into Gremlin code.

Installing the console requires only downloading and unpacking the current version [9] on a Linux computer. If Java 8 is also already installed, the console is immediately ready to launch. A database – the Apache TinkerGraph in-memory model – is also included as a plugin. A selection of sample data is even included in the package.

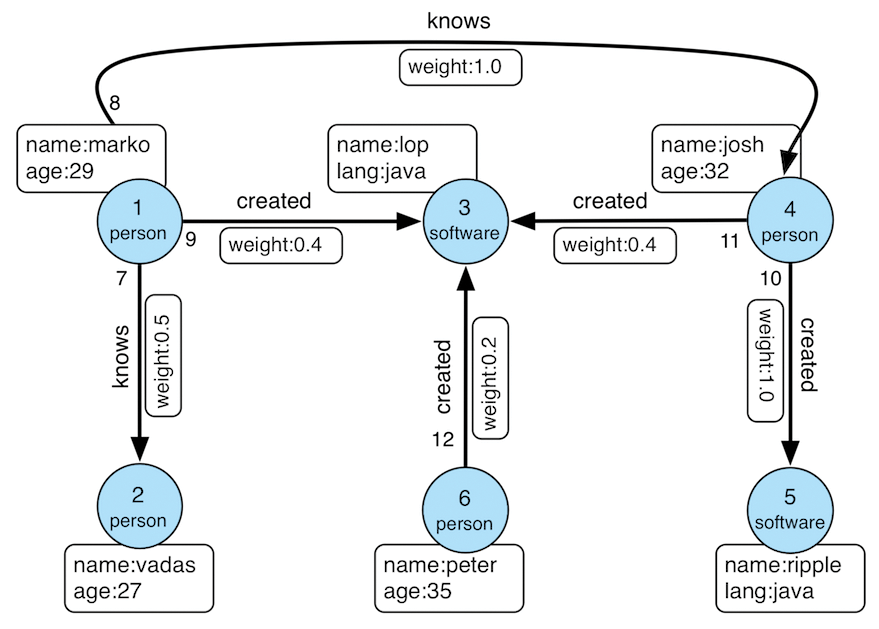

To start the console from the directory created during unpacking, type bin/gremlin.sh. A very small sample database (Figure 4) can be created with the command from the first line of Listing 2, which loads the Modern database from the subdirectory data/, so named because it is a more modern version of an older example with six nodes and six edges.

Listing 2: Gremlin Database Example

01 graph = TinkerFactory.createModern()

02 ==>tinkergraph[vertices:6 edges:6]

03

04 gremlin> g = graph.traversal()

05 ==>graphtraversalsource[tinkergraph[vertices:6 edges:6], standard]

06

07 gremlin> g.V().label().groupCount()

08 ==>[software:2,person:4]

09

10 # Names of all persons:

11 gremlin> g.V().hasLabel('person').values('name')

12 ==>marko

13 ==>vadas

14 ==>josh

15 ==>peter

16

17 # Name of person with ID 1

18 gremlin> g.V(1).values('name')

19 ==>marko

20

21 # The name and age of the persons who know the person with ID 1:

22 gremlin> g.V(1).outE('knows').inV().valueMap('name', 'age')

23 ==>[name:[vadas],age:[27]]

24 ==>[name:[josh],age:[32]]

25

26 # Which of these people who know the person with ID 1 is less than 30?

27 gremlin> g.V(1).out('knows').has('age', lt(30)).values('name')

28 ==>vadas

29

30 # Display matches step-by-step

31 gremlin> g.V().outE('created').inV().next()

32 ==>v[3]

33

34 gremlin> g.V().outE('created').inV().next(2)

35 ==>v[3]

36 ==>v[5]

The database contains information about a small group of software developers and their products. Some of the developers know each other and have contributed to the same projects. Additionally, Gremlin needs a traversal source, which describes how it should move through the graph. The easiest way to do this is to use the standard path (Listing 2, lines 4 and 5).

To output all the nodes, you use g.V(), and to list all edges, you use g.E(). The queries are generally organized in steps separated by dots. As previously mentioned, g is the traversal source, and V() is an iterator that runs step by step through all nodes. Further steps can now output properties of the respective node (.values()) or check it for certain conditions (.has()).

Additionally, filter results can be aggregated. For example, what happens when the user asks the database how many nodes of different types it has (Listing 2, lines 7 and 8)? Further examples of simple queries are demonstrated in lines 10-28. In principle, each query walks along the tree, which can be observed several ways. You can display hits, step by step (e.g., the first node a created edge points to; lines 31 and 32), the next two (lines 34-36), and so on.

With .toList(), you can return all matches in one fell swoop, and .toSet() returns all matches, but without duplicates. Also, you can retrieve the path that was traversed to get to a search hit. The call in Listing 3 (first query) displays the software projects in which developer Josh was involved.

Listing 3: Simple Queries

gremlin> g.V().hasLabel('person').has('name','josh').outE('created').inV().values('name')

==>ripple

==>lop

gremlin> g.V().hasLabel('person').has('name','josh').outE('created').inV().values('name').path()

==>[v[4],e[10][4-created->5],v[5],ripple]

==>[v[4],e[11][4-created->3],v[3],lop]

gremlin> g.V().outE('created').has('weight', 1.0).inV().values('name')

==>ripple

gremlin> g.V().outE('created').has('weight', 1.0).outV().values('name')

==>josh

The path determination (second query) first finds node 4 with label person and name property josh; from there, it then traces outgoing edges 10 and 11, which are both tagged with the created property (i.e., they must refer to software). By doing so, it finds nodes 3 and 5, which stand for lop and ripple.

In the case of a software product that someone has developed alone, the weighting of the created edge needs to be set to a value of 1.0, as shown in the third query. The final query finds the programmer who created a project on their own by looking for created edges with a weighting of 1.

These queries have all been simple thus far. Traversals also can follow branches in the graph (branching traversals), be processed recursively (recursive traversals), follow paths (path traversals), or refer to subgraphs (subgraph traversals). The step-by-step structure, however, always remains the same, and the number of commands required for the steps does not become unmanageable. In this article, though, I'll stick with simple queries.

If you want to explore the Gremlin language on your own, the Gremlin Console comes with other sample datasets, some of them far more extensive, like the eponymous database of Grateful Dead songs that includes information about the vocalists and composers and the order in which they appeared live and on vinyl. This database has many hundreds of nodes and thousands of edges and is tricky to visualize clearly.

(No) Puzzles

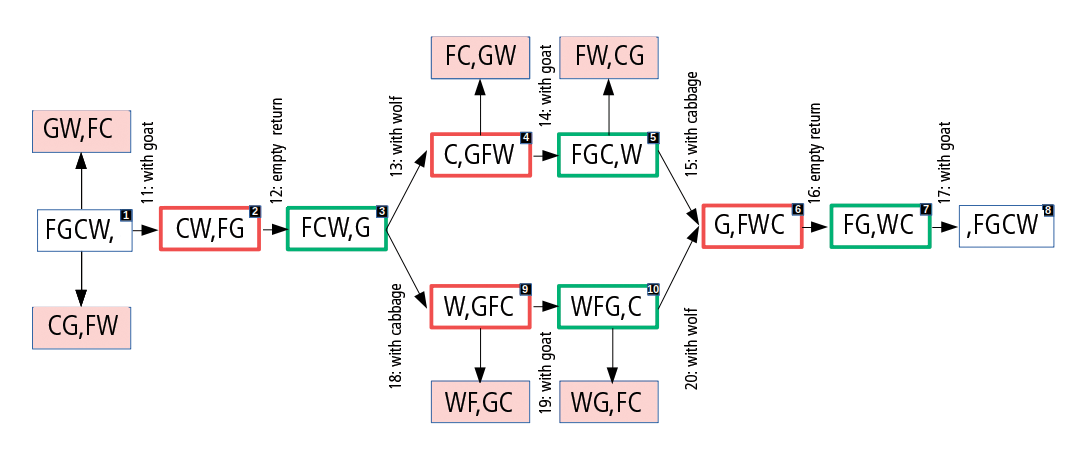

Take the classic river-crossing riddle: A farmer arrives at a river with a wolf, a goat, and a cabbage. He can only carry one animal or the cabbage in his boat at a given time. Furthermore, he cannot leave the wolf and the goat, or the goat and the cabbage, alone on a bank, because the former would eat the latter. How does he get all his belongings across the river unharmed? Spoiler alert! If you want to work it out yourself, read no further.

First, the farmer takes the goat to the other side and goes back empty. Then he picks up the wolf, but takes the goat back with him. Next, he can take the cabbage across and leave it with the wolf, and finally he can take the goat across the river.

This procedure can be represented as a graph with nodes as the respective end states of a crossing (Figure 5). The letters FGCW, for example, stand for farmer, goat, cabbage, and wolf. The comma symbolizes the river. Unauthorized states are colored red. Each step has an action the farmer could take to undo the transport that has just taken place, but this action would not make any progress and is not shown here for the sake of clarity.

Before saving the graph, you can simplify it further by omitting the reverse actions and the transitions to the illegal states. Whatever remains can be stored directly in the database without the need to design a schema or define tables first, unlike relational models. You could now enter all nodes and all edges interactively one after the other. However, it is easier and less prone to error to create the database content in a file (Listing 4) in XML format (GraphML) and then load this file into the Gremlin console with the commands in Listing 5.

Listing 4: River XML Database

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<graphml xmlns="http://graphml.graphdrawing.org/xmlns" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation="http://graphml.graphdrawing.org/xmlns http://graphml.graphdrawing.org/xmlns/1.1/graphml.xsd">

<key id="labelV" for="node" attr.name="labelV" attr.type="string" />

<key id="name" for="node" attr.name="name" attr.type="string" />

<key id="labelE" for="edge" attr.name="labelE" attr.type="string" />

<graph id="G" edgedefault="directed">

<node id="1">

<data key="labelV">state</data>

<data key="name">FGCW,</data>

</node>

<node id="2">

<data key="labelV">state</data>

<data key="name">CW,FG</data>

</node>

<node id="3">

<data key="labelV">state</data>

<data key="name">FCW,G</data>

</node>

<node id="4">

<data key="labelV">state</data>

<data key="name">C,GFW</data>

</node>

<node id="5">

<data key="labelV">state</data>

<data key="name">FGC,W</data>

</node>

<node id="6">

<data key="labelV">state</data>

<data key="name">G,FWC</data>

</node>

<node id="7">

<data key="labelV">state</data>

<data key="name">FG,WC</data>

</node>

<node id="8">

<data key="labelV">state</data>

<data key="name">,FGCW</data>

</node>

<node id="9">

<data key="labelV">state</data>

<data key="name">W,GFC</data>

</node>

<node id="10">

<data key="labelV">state</data>

<data key="name">WFG,C</data>

</node>

<edge id="11" source="1" target="2">

<data key="labelE">action</data>

<data key="name">with_goat</data>

</edge>

<edge id="12" source="2" target="3">

<data key="labelE">action</data>

<data key="name">empty_return</data>

</edge>

<edge id="13" source="3" target="4">

<data key="labelE">action</data>

<data key="name">with_wolf</data>

</edge>

<edge id="14" source="4" target="5">

<data key="labelE">action</data>

<data key="name">with_goat</data>

</edge>

<edge id="15" source="5" target="6">

<data key="labelE">action</data>

<data key="name">with_cabbage</data>

</edge>

<edge id="16" source="6" target="7">

<data key="labelE">action</data>

<data key="name">empty_return</data>

</edge>

<edge id="17" source="7" target="8">

<data key="labelE">action</data>

<data key="name">with_goat</data>

</edge>

<edge id="18" source="3" target="9">

<data key="labelE">action</data>

<data key="name">with_cabbage</data>

</edge>

<edge id="19" source="9" target="10">

<data key="labelE">action</data>

<data key="name">with_goat</data>

</edge>

<edge id="20" source="10" target="6">

<data key="labelE">action</data>

<data key="name">with_wolf</data>

</edge>

</graph>

</graphml>

Listing 5: Loading the Database

gremlin> conf = new BaseConfiguration()

==>org.apache.commons.configuration.BaseConfiguration@1bbae752

gremlin> graph = TinkerGraph.open(conf)

==>tinkergraph[vertices:0 edges:0]

gremlin> g=graph.traversal()

==>graphtraversalsource[tinkergraph[vertices:0 edges:0], standard]

gremlin> g.io("/home/jcb/river.xml").with(IO.reader,IO.graphml).read().iterate()

Now you can start a query at the node that contains the start position (FGCW,). From then on, you need to trace all outgoing edges and incoming nodes until the query finds the node that represents the final state after the river crossing (,FGCW). At this point, you want the database to output the path taken (.path(); the example has two equivalent paths). Listing 6 discovers the solution to the riddle. The output from the database lists the ID of the node (e.g., [1]), followed by the ID of the outgoing edge (e.g., [e11]) and a description of the edge with start and destination node and transported goods (e.g., 1-with_goat->2). After reaching the node, it continues in the same way until the query has arrived at the destination node.

Listing 6: Solving the Puzzle

gremlin> g.V().has('name','FGCW,').repeat(outE().inV()).until(has('name',',FGCW')).path()

==>[v[1],e[11][1-with_goat->2],v[2],e[12][2-empty_return->3],v[3],e[18][3-with_cabbage->9],v[9],e[19][9-with_goat->10],v[10],e[20][10-with_wolf->6],v[6],e[16][6-empty_return->7],v[7],e[17][7-with_goat->8],v[8]]

==>[v[1],e[11][1-with_goat->2],v[2],e[12][2-empty_return->3],v[3],e[13][3-with_wolf->4],v[4],e[14][4-with_goat->5],v[5],e[15][5-with_cabbage->6],v[6],e[16][6-empty_return->7],v[7],e[17][7-with_goat->8],v[8]]

The result is obvious in this case and could be read off from the graph at first glance, but if you were to store something more complex like the public transport network in Munich as a graph and search for a connection between two points (which might require changing trains one or more times), the task would no longer be trivial – especially if the edges are weighted by distance, travel time, or travel costs, and you are looking for the shortest, fastest, or cheapest route. The method also works even if the graph is too large to be visualized and surveyed.

Hands On

Beyond such finger exercises: For which applications are graph databases best suited in practical use? Are there any useful examples? In this article, I show you some impressive potential applications with genuine case studies.

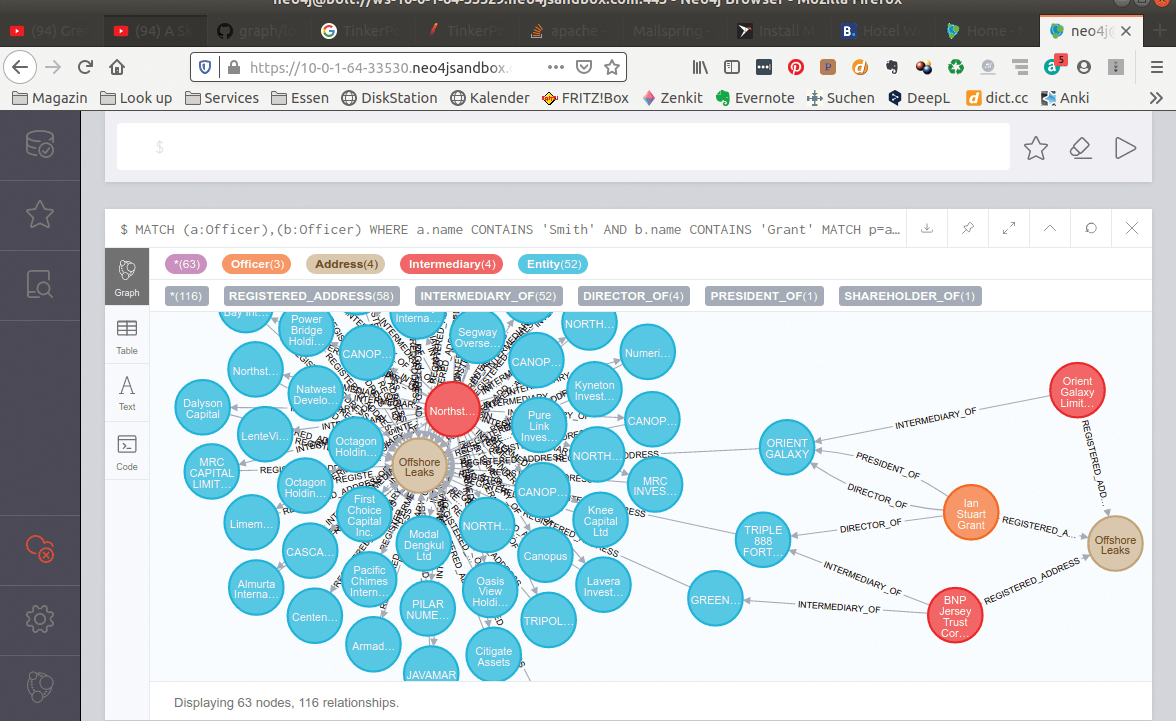

Say Ms. X is an employee of company Y and lives in Z. She has an unsuspicious current account at a local savings bank. Mr. A lives at exactly the same address and is employed by B as a manager. B has subsidiary C, and it maintains an offshore account in the Cayman Islands. Ms. X's connection to this account is only indirect, but graph databases are particularly useful for tracing such connections around several corners. Indeed, the reporters of the ICIJ used this tool for months of analysis of the 2.6TB of leaked tax data from the Panama Papers – as mentioned at the beginning of the article. The well-known Neo4j open source graph database makes the data available to everyone free of charge for testing in its sandbox (Figure 6), accessible online from a browser [10].

Knowledge represented in the form of an ontology (i.e., a formally ordered hierarchy of terms) results in a tree-like graph. A semantic network, which also represents terms and their mutual relationships, is also a graph. Within the individual scientific disciplines, ancestry or kinship relationships in biology or history are a good example. The research project Nomen et Gens (NeG) [11], for example, stores in a graph database more than 21,500 individual records of names and persons in continental Europe between AD400 and 800, together with their relationships.

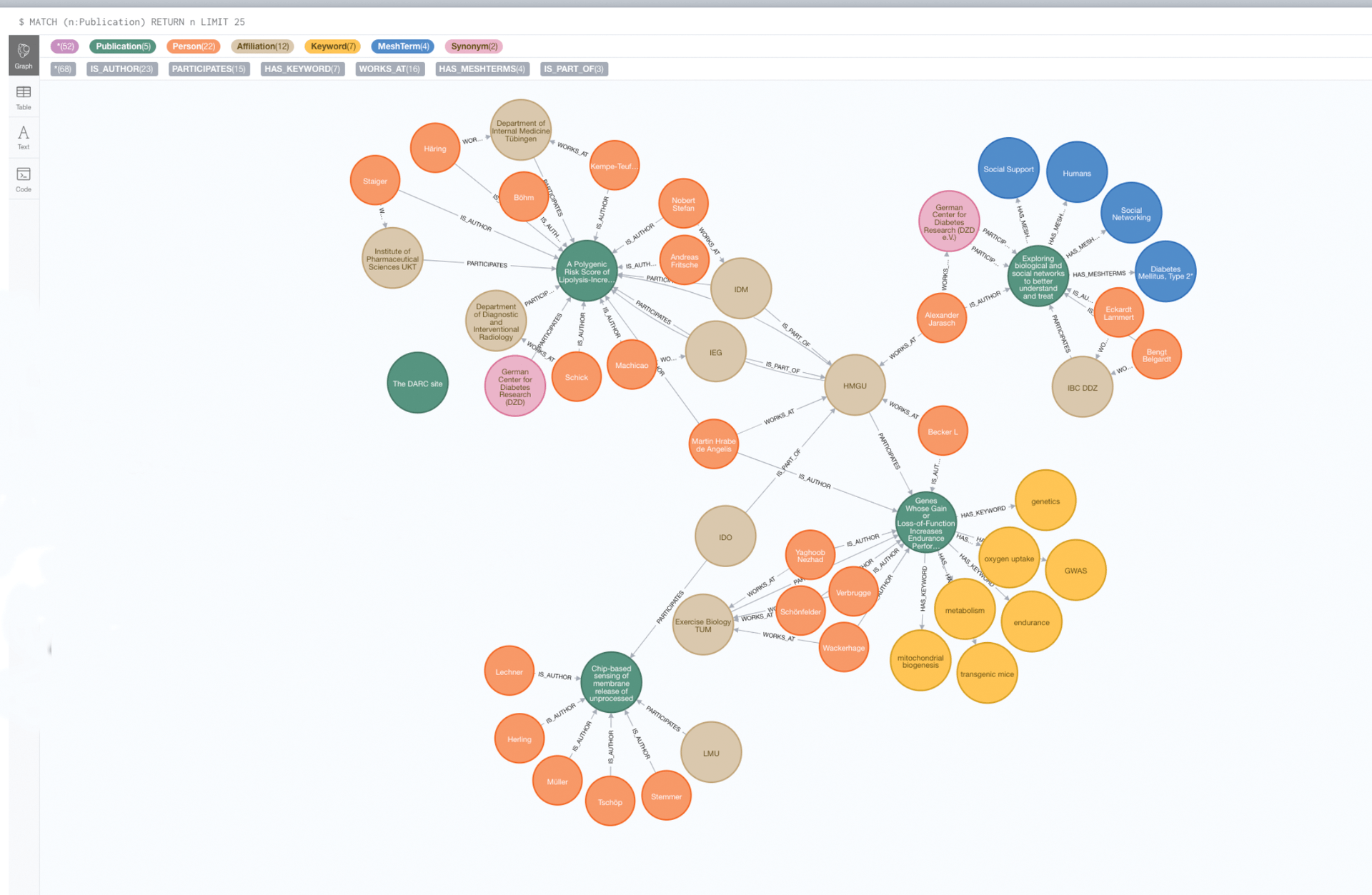

Another example from science is the cross-location, cross-discipline, and cross-species networking of research data on diabetes at the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD) in the project Graphs to Fight Diabetes [12]. The database links many heterogeneous data items, including measured values, data from basic research, clinical studies or animal experiments, microscope images, and information on metabolic pathways, genes, or proteins, but also side effects and finally publication references. This combination results in a kind of meta-database that the researchers hope will help them identify new subtypes of the disease and find new, individualized steps for prevention or therapy.

The database currently comprises about 2.1 billion nodes and 3.8 billion edges and weighs in at about 480GB. It is currently used by around 450 scientists at the DZD but is due to be expanded to other centers of health research this year.

What is helpful here is that the relationships between the contents can be visualized (Figure 7). In this way, queries can also be put together by pointing and clicking, without necessarily having to learn one of the supported query languages. In the simplest case, you just need to select two nodes and choose Find Shortest Path from the context menu by right-clicking. Of course, you can also program queries in Cypher or a script language like Python or R.

Yet another example of the efficacious use of a graph database is the Smart Infrastructure project at Siemens (see the "Intelligent Twins" box).

Conclusions

Where the task in hand is primarily a matter of processing statements about relations between people, things, events, points in time, or places, graph databases are superior to their relational siblings for several reasons. Queries for relationship chains in particular, such as my friends' friends, need recursive joins in the relational world, which are very complex and slow and become all the more evident the deeper the concatenation goes. Graph databases are orders of magnitude more powerful for such problems. NoSQL databases like key-value stores or document-oriented databases have similar disadvantages. These databases often shift the data processing onus to the application when relationships are queried.

Another advantage of graph over relational databases is that they can be extended by new relations at any time and do not require a pre-defined schema. This circumstance also makes them more agile because they adapt better to a step-by-step expansion of the program logic. Furthermore, relational schemas, such as those that can be designed in an entity relationship model, only support simple and unidirectional relationships, whereas in a graph database, they have specific properties and can be bidirectional.

The opportunities to capitalize on these advantages are constantly growing as the world becomes increasingly interconnected. The value of data lies not only in sheer volume, but in the connections, and graph databases are the means of choice for representing, storing, and querying these connections .