WiFi 6 in the enterprise

Fleet of Foot

In the history of wireless networks, many innovations have already been exaggerated by providers as a major breakthrough yet, in the end, did not really meet the expectations of users. In the case of WiFi 6, however, the expectations are justified. The 802.11ax specification is the first WiFi standard developed with the premise that it will overtake wired as the primary means of connecting terminal devices to the network – in the office or on the shop floor. (See the "WiFi 6 Goals" box.)

The earlier WiFi generations were designed for occasional use and less for downloading large data volumes. The 802.11ac specification (WiFi 5) certainly made WiFi networks faster, but in reality, this variant only partially improved an outdated concept and increased transmission speed.

Every WiFi user has certainly connected to a WiFi access point (AP) at some time at a conference center, in a football stadium, or in another public space. Everything works fine until the moment the speaker starts their presentation or the spark fails to fly between the onstage musicians and the audience, prompting many people to open up private communication channels (email, Snapchat, Twitter, WhatsApp, Facebook, etc.). All of a sudden, the WiFi that had worked so well before is extremely slow and becomes unusable.

The causes of WiFi problems do not always lie in the speed of the system. The 802.11ac Wave 2 specification (WiFi 5) now provides speeds around the gigabit mark. This bandwidth should be sufficient for most applications. The bigger problem that WiFi networks face can best be described as "congestion." Wireless networks are comparable to highways: Normally, the capacity of multilane highways is sufficient for free-flowing traffic. However, if an extremely large number of people try to use the same freeway routes at the same time (e.g., to get to a large event), the bandwidth of the route is not sufficient to transport the cars efficiently, inevitably leading to traffic congestion. If many people try to access the WiFi network and communicate simultaneously, a temporary overload also occurs.

The WiFi 6 standard, based on the successful practical solutions provided by Long-Term Evolution (LTE) technology, promises to solve the congestion problem. WiFi 6 is expected to be ratified in the middle of 2020, with additional features (including operation in the 6GHz band) certified over the next couple of years, although some commercial pre-standard products are already available today.

Who Should Use WiFi 6?

All companies currently using WiFi 4 (802.11n) or older WiFi standards are candidates for an upgrade. Market analysis firm ZK Research estimates that up to 49 percent of all companies are still using WiFi 4 somewhere on their corporate networks [1]. This technology is almost a decade old and has reached the end of its performance and reliable lifetime. These customers should skip WiFi 5 (802.11ac) and directly deploy WiFi 6. An intermediate step to WiFi 5 would probably result in another WiFi upgrade in two to three years. In contrast, the direct upgrade to WiFi 6 promises to include at least five years' worth of updates.

WiFi 6 Is Far Faster

The products based on the 802.11ax standard work about four to 10 times faster than the WiFi standards used so far, because WiFi 6 has more and wider transmission channels that significantly increase throughput. (See Table 1 for the specifications of various WiFi standards.) Assuming the speed is increased fourfold when using 160MHz channels, the speed of a single WiFi 6 stream is 3.5Gbps. The equivalent WiFi 5 connection would be a transfer speed of 866Mbps.

Tabelle 1: Comparison of WiFi Standards

|

Old Name |

802.11b |

802.11a |

802.11g |

802.11n |

802.11ac |

802.11ax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year of publication |

1999 |

1999 |

2003 |

2009 |

2013 |

2020 |

|

Frequency (GHz) |

2.4 |

5 |

2.4 |

2.4 and 5 |

5 |

2.4 and 5 |

|

Modulation method* |

DSSS/OFDM |

DSSS/OFDM |

DSSS/OFDM |

OFDM |

OFDM |

OFDMA |

|

Maximum data rate (Mbps) |

11 |

54 |

54 |

800 |

6900 |

9600 |

|

Spatial streams |

1 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

8 |

8 |

|

MIMO# |

– |

– |

– |

MIMO/SU-MIMO DL |

MU-MIMO |

UL/DL MU-MIMO |

|

New Name |

WiFi 1 |

WiFi 2 |

WiFi 3 |

WiFi 4 |

WiFi 5 |

WiFi 6 |

|

*DSSS, direct-sequence spread spectrum; OFDM, orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing; OFDMA, OFDM access. |

||||||

|

#MIMO, multiple in/multiple out; MU, multiuser; SU, single user; DL, downlink; UL, uplink. |

||||||

In a 4x4 multiple in/multiple out (MIMO) environment, WiFi 6 devices achieve a maximum total capacity of 14Gbps. A wireless client that supports two or three streams in parallel can easily accommodate them in a 1Gbps connection. If the channel width is reduced to 40MHz, which can happen at any time in crowded radio fields, only a single 802.11ax stream of around 800Mbps with a total capacity of 3.2Gbps would be available. Regardless of the channel size, the new WiFi 6 specification provides an enormous increase in transmission speed and overall capacity.

Fewer Data Jams

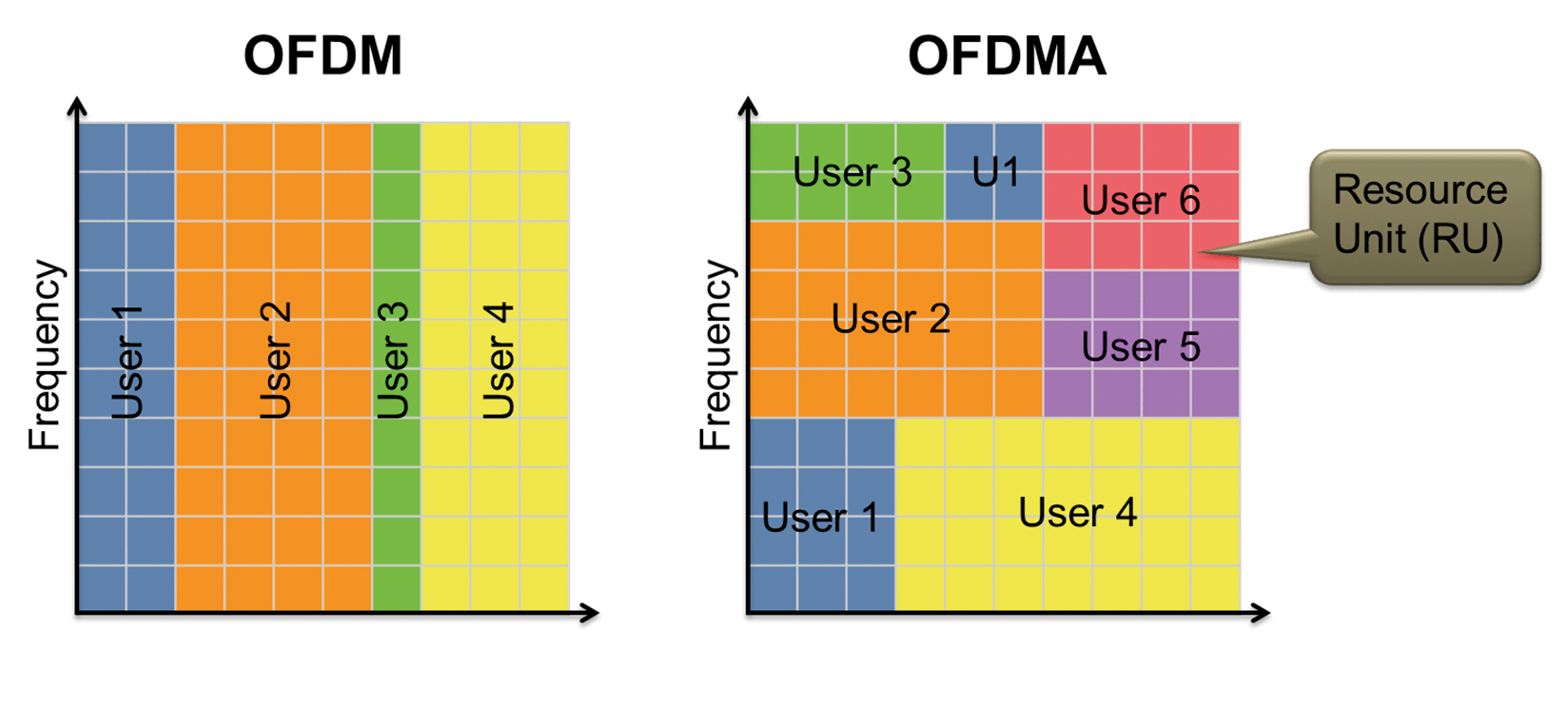

LTE products use a technology called orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing access (OFDMA). In previous WiFi versions, the transmission channels remained open until the data transmission was completely terminated, which is comparable to queues at a ticket counter. The waiting customers can only move forward when the ticket counter is free. In the case of the WiFi process based on multiuser MIMO (MU-MIMO), this means four ticket counters and four lines (one per sales counter). The next person waiting in line can only be served when a desk becomes free, which reduces the time each person has to wait for service, thus increasing the speed of the system.

The OFDMA method splits each channel into hundreds of smaller subchannels (Figure 1). Each of these subchannels uses a different frequency. The signals are then encoded orthogonally and stacked accordingly. In the ticket booth analogy, you have to imagine a counter clerk who is able to serve several customers simultaneously. While the employee is going through the process of taking payment for a ticket, they can already start serving the next customer. Instead of alternately listening to the respective messages transmitted over the radio medium, OFDMA allows up to 30 clients to share each channel.

OFDMA also improves in terms of efficiency as the number of users increases, because the available airtime – the time the radio medium is available to the user for transmission – can be used in a far more effective way. Of course, this presupposes that a significant proportion of terminals are WiFi-6-compatible. To achieve noticeably higher throughput, perhaps 30 percent of the terminals need to support the new standard. From a network perspective, the transmission path appears less congested than with WiFi 5. Another advantage is that the 2.4 and 5GHz bands can be combined, giving users even more channels for data transmission. The WiFi 6 specification also uses quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) coding, which ensures that the packets transmitted can contain even more data. The OFDMA mechanism also enables granular Quality of Service (QoS), which allows applications with high bandwidth requirements or delay-sensitive requirements specifically to be prioritized in both the uplink and downlink directions.

Many users believe that by increasing the transmission power at the access point, better range and higher data rates are possible. However, because of the typically lower transmission power of end devices, this is not true in most cases. If the end devices are not able to acknowledge received packets with a comparable signal level, the access point assumes poor signal quality and thus reduces the data rate. To achieve maximum data rates requires symmetry between the received signal strengths to circumvent this problem. However, increased sensitivity of access point antennas only helps to a limited extent to compensate for the different transmission powers.

Same Channel, No Interference

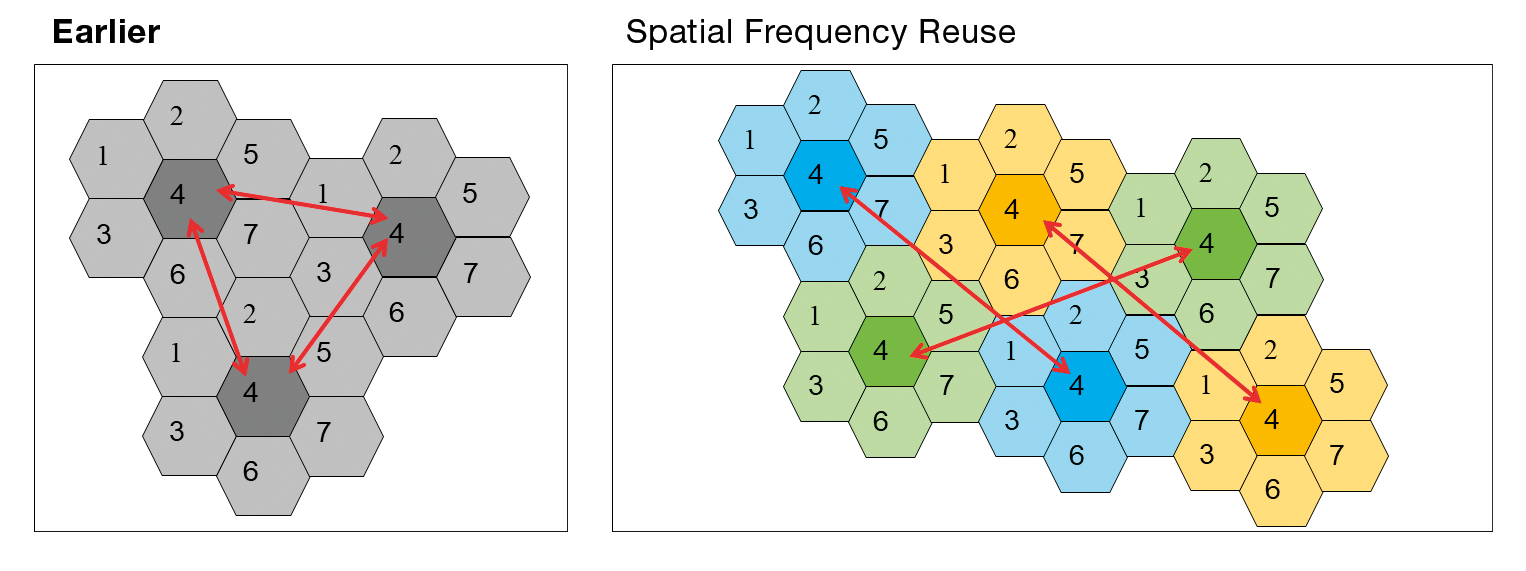

Spatial Frequency Reuse (SFR) technology ensures that neighboring WiFi stations are allowed to transmit on the same radio channel at the same time. Normally, they would interfere with each other. However, in some situations the signal strength and signal-to-noise ratio in the individual cells are large or good enough to allow transmissions to take place.

This feature improves channel capacity by allowing access points to make smarter decisions about when to transmit data. In general, it can be assumed that cell sizes will have to be reduced in future WiFi plans to benefit from the higher data rates offered by the new QAM-1024 modulation method.

According to the 802.11 standard, the service set refers to all devices on a WiFi network. A basic service set (BSS) is created by synchronizing the basic parameters of several devices that can be addressed by a service set identifier (SSID). The BSS coloring method was introduced with the 802.11ah standard and is used to assign a different "color" to each BSS. To increase capacity in dense WiFi environments, the ability to reuse frequencies between BSSs has to increase. However, with the media access rules used in the past, the WiFi terminals were moved from one BSS to another co-channel BSS without increasing network capacity (Figure 2).

The BSS coloring method available in WiFi 6 optimizes the competition overhead of the devices because of overlapping transmission channels. By doing so, it enables spatial reuse of these channels. WiFi 6 devices can distinguish between different BSSs by adding a number (color) to the physical layer (PHY) header. The new channel access behavior is based on this assigned color. For example, the same color bit indicates intra-BSS communication (communication on the same WiFi network), whereas different color bits indicate inter-BSS communication (communication between different WiFi networks). Inter-BSS detection means that a WiFi receiver has to view the medium as busy and postpone its transmission until the channel is free.

An adaptive implementation can increase the signal detection (SD) threshold for inter-BSS frames while maintaining a lower threshold for intra-BSS traffic. BSS coloring thus reduces channel conflicts that result from the previously valid 4dB signal detection thresholds. The aim of BSS coloring is therefore to enable the reuse of transmission channels without causing significant interference. The crucial point here is that the medium is only considered occupied if a color is unambiguously identified by a transmitter.

Improved Battery Life

Each new WiFi standard extends battery life, because the radio range is usually increased and data is transmitted faster. One previously unchanged burden on the battery life of clients was always having to check whether the access point was available and ready for data transmission. WiFi 6 therefore introduces a new feature known as target wake time (TWT) scheduling.

TWT allows access points to tell clients when they can go to sleep and provides a schedule for when the device should wake up. These sleep times can be very short periods of time (literally milliseconds between sleeping and waking). TWT nevertheless increases the amount of time the device is idle, therefore improving battery life. For WiFi 6, the TWT mechanism enshrined in the 802.11ah standard has been modified to support WiFi participants who have not negotiated a hibernation agreement with the AP.

TWT is very useful for both mobile and Internet of Things (IoT) devices. TWT uses fixed policies on the basis of expected traffic activity between 802.11ax clients and an 802.11ax AP to set a scheduled wake time for each client, which means that WiFi 6 IoT clients can sleep for hours or even days.

With the 802.11ac standard, the TWT function is only supported by 80MHz-capable WiFi clients, whereas the new WiFi 6 specification also supports 20MHz clients. Therefore, TWT is available for low-power, low-complexity devices (e.g., portable devices, sensors, IoT devices).

Precise Device Synchronization

Thanks to WiFi technology, almost all devices can now be connected wirelessly. In the past, this technology still suffered from minor timing difficulties, like where synchronicity was important for video and audio streaming. Now the Wi-Fi Alliance has found a way to overcome this shortcoming. The Wi-Fi TimeSync certification industry group has published a specification for precise time synchronization for WiFi devices [2].

When WiFi technology came onto the market more than 20 years ago, only data that was not time-critical had to be transmitted without errors between computers. Clock synchronization was not an issue. Because of the deep penetration of WiFi technology in the fields of home entertainment and media production, the timing question has become significant.

For example, stereo sound can be produced over loudspeakers located on opposite sides of a room. If WiFi is used to transmit the information, the connecting cables between the transmitter and the loudspeakers are no longer necessary. However, as long as these devices do not output the signals synchronously, the stereo effect is lost. Outputting the right sound in a home theater becomes even more difficult when the TV controls a subwoofer and several speakers wirelessly.

Wi-Fi Certified TimeSync was developed for exactly these kinds of applications. It ensures that the clocks on the various devices are synchronized to less than a microsecond, which allows each component to perform its task at the right time.

TimeSync not only synchronizes the clocks on each certified device automatically, it can also be used to synchronize entire groups of devices. For example, the systems of several manufacturers can work together in a time-dependent application. (See the "Applications for Wi-Fi TimeSync" box.)

Preparing for WiFi 6

The availability of the very first WiFi 6 devices on the market does not mean that products complying with the final standard will be available any time soon. Therefore, administrators still have time to familiarize themselves with the new technology and take steps to prepare for WiFi 6:

1. Ensure that the wired network resources are up to date. The high bandwidths provided by WiFi 6 affect the edge and core of corporate networks. Key WiFi 6 features include power delivery of more than 30W through Power over Ethernet (PoE+), multigigabit interfaces (1/2.5/5Gb Ethernet) at the edge, and 40Gbit Ethernet uplinks to the core. Uniform management is also one of the mandatory functions of a modern LAN/WiFi infrastructure, allowing security and access policies to be managed from a single dashboard, while integrating wired and wireless networks.

2. One important factor in the migration to the 11ax standard that should not be underestimated is the wired infrastructure. Currently available WiFi APs use uplinks at speeds of 2.5 or 5Gbps. In many companies, these new Ethernet standards need to be introduced for the first time.

3. Begin to integrate additional functions from the field of artificial intelligence. With WiFi 6, practically all company resources can be connected over a common network, which naturally increases the complexity of the networks and the necessary transport mechanisms. According to a survey by ZK Research, 61 percent of companies are not sure that all devices active on the network are known, or whether these devices should be on the network at all [3]. This problem gets worse the more devices you connect. Therefore, a management tool based on machine learning is essential for the success of WiFi 6.

4. In many enterprises, closed networks for certain business functions are operated in parallel and strictly separated for security reasons. Examples include the electronic shelf labeling network in retail stores, the production machines and robots in manufacturing areas, and the radiology networks in hospitals. Digital transformation and IoT are converging these networks. IT departments need to prepare by analyzing and understanding the effect of a drastic increase in network size and the use of additional protocols such as BLE or Zigbee and how they affect IT security.

Potential Competitor

Every time a new mobile phone standard comes out, the "end of WiFi" is propagated. In the case of 3G, it was claimed that this network would replace all IEEE 802.11b/g solutions. This story was repeated for 4G (LTE), and it was claimed that 802.11ac solutions would soon end up in the trash. With 5G, the message is once again that this technology will oust all competing products inside and outside buildings.

Mobile telephony and WiFi are still two largely separate worlds that users can use with ease, but switching between the worlds is now possible. For example, most mobile phones automatically switch to the cellular network if the WiFi connection is not working, although you can encounter some problems when switching back and forth, which from the point of view of mobile operators, is not always desirable.

For cost reasons, 5G will probably not replace the corporate WiFi, but only supplement it. WiFi 6 has adopted many innovations in wireless technology and now offers reliable, dense, high-throughput connectivity. However, the most important arguments for installing WiFi networks in companies are:

- WiFi infrastructures can be set up by anyone in the shortest possible time and operated without an intermediate provider.

- The ongoing operation of a WiFi network has no significant costs and no expensive licenses or contracts per client.

- Companies with their own wireless infrastructure can set up independently and have complete control over their networks.

Therefore, companies have no reason to replace something that has worked well so far.

Conclusion

The WiFi 6 era is coming and companies will have to analyze how to use this new technology and gradually prepare corporate networks for the new requirements. With comprehensive pre-planning, WiFi 6 deployment should be a smooth and risk-free process in the foreseeable future.