Solving the security problems of encrypted DNS

Double-Edged Sword

Dynamic Name Service (DNS) is a fundamental Internet service. As soon as you enter a computer name (e.g., http://www.mozilla.org), DNS finds the corresponding IP address, 63.245.208.195 in this case. Without DNS you would have to know IP addresses by heart and enter them directly in your web browser's address bar.

The DNS data packets pass through the network without encryption or signatures. Only a 16-bit random number, intended to ensure the assignment of the request and response, provides rudimentary protection. The requesting client accepts the first incoming response with the correct random number and stores it temporarily in its cache. An attacker need only respond faster than the official DNS server to redirect the request. Inserting fake DNS entries in the cache is known as DNS cache poisoning.

Because all DNS traffic is unencrypted, it can be monitored and evaluated – by the provider or by your employer, among others. If an admin is looking to block undesirable access to servers that distribute malware in this way, unencrypted DNS can be advantageous.

About DNS Security

DNSSEC [1] is an established, but still not sufficiently widespread, standard for generating signed and therefore verifiable DNS responses. Providers and organizations that use at least this standard to thwart attacks, such as DNS spoofing and DNS cache poisoning, would be very desirable. At the moment, however, an overriding concern seems to be that using it makes DNS even more prone to error. Many large enterprises therefore still currently do without DNSSEC.

DNSSEC does not encrypt the content data (confidentiality) and only signs the data (integrity). Essentially, two keys are required per domain: one to sign the domain data (marked with code 256; typically 1024 bits) and a second to sign the keys (code 257; typically 2048 bits). The keys can be displayed with

dig <domain> DNSKEY

(Listing 1). With some versions of dig, the reverse parameter order also works. To enable a trouble-free key change, old and new keys can be used at the same time.

Listing 1: Displaying Keys

01 ;; ANSWER SECTION: 02 mozilla.org. 6074 IN DNSKEY 257 3 7 03 Av//szWRDSGz3g4JkiuQqws79YZ6nwxk0f9PF9MCQSYrRGd0f4Vuuouf 04 aKdeFvdeY4x9tGmh7FQ51Qi6EEr9LLy2Q8qTtEuN2fJ4PnWBNRfKwhWb 05 SNQWvq1jwhsXlsAelLz7tO5kptI7TO16p2ncpnhJqfzT5mWJ4nK76YPZ 06 lu+MZlIYJOMv/OQWD2nVmsjXeO0dnsrL8MyC5wdyPy2gbksWBscsbwN2 07 34APEYO48B6sovy2fuTVWnj7LDsEh3NzrhjGYlhWmtvrXg3mlFelz/MZ 08 XrK6uAlp6206Hc669ylfhIcD9d7w0rc9Ms1DFCh5wzVRbnJJF51mW2nC 09 mh5C8E7xSw== 10 mozilla.org. 6074 IN DNSKEY 256 3 7 11 AwEAAcY1VDPtMAXJPEwna184sRuU6QGYWnccTAyJhpzYQ+AsfK8eZVYS 12 iA2g8G24ZIvMrzOp6KQdx0XET6/QIO5xD7B0QH9YNXatVsXtzce+9Q9X 13 klmc78oKRKrVw969aEX91kjRXf6pjRXckJxXdXetxzuL6/E4bMKjQCGX 14 yJI20TGx

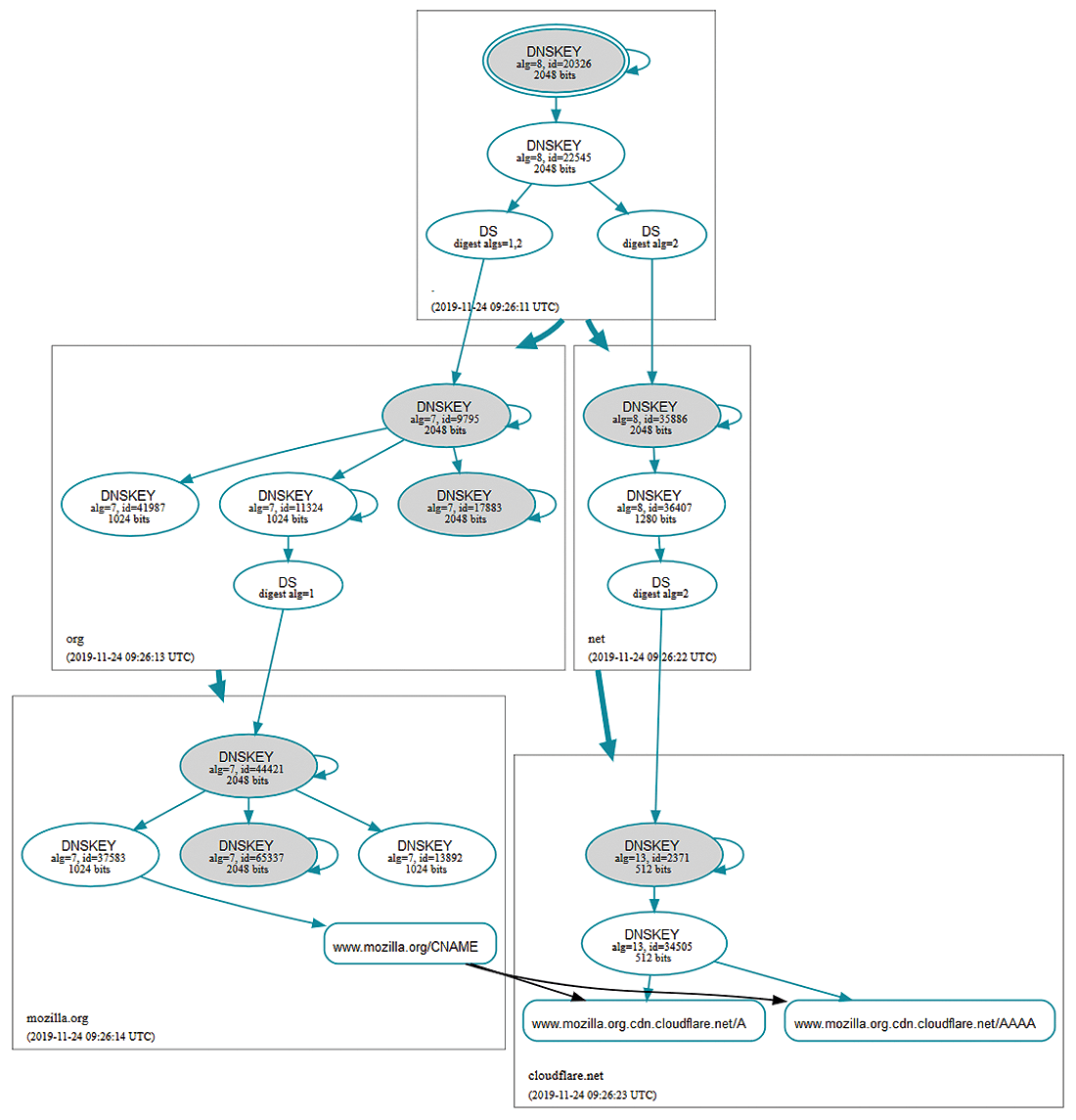

Confirming the keys follows a hierarchy. The DNS root servers have provided support for DNSSEC and corresponding keys since 2010. They use them to sign the keys, which in turn are used to sign keys for the top-level domains. The key of the top-level domain (e.g., .org) is then used to sign the keys of the other domains (e.g., mozilla.org). This hierarchy can be visualized easily with tools like DNSViz [2] (Figure 1).

The command

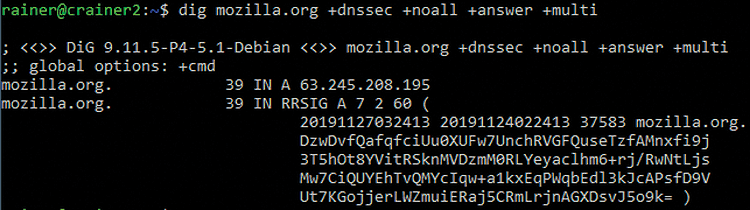

$ dig mozilla.org +dnssec +noall +answer +multi

displays the signature in the DNS response (RRSIG) (Figure 2). Manual verification only works in a multistage, complex process, so a DNSSEC-compatible resolver makes sense here (see the "Pi-hole DNSSEC Resolver" box).

In principle, the key distribution mechanism for DNSSEC can also distribute keys for any other application, such as TLS, IPsec, email encryption, and so on. A separate protocol field exists for this purpose during key transmission.

Privacy

The confidentiality of DNS queries can only be ensured by encrypting DNS traffic. One solution for this is DNSCrypt [4], which exchanges unmodified DNS packets in encrypted form over port 443 but does not use the HTTPS protocol. Numerous DNS providers support DNSCrypt.

Another possibility is DNS over TLS (DoT) [5], which routes DNS traffic over a TLS-encrypted connection on port 853. One of the protagonists of this protocol is Google. Android supports DoT from version 9 "Pie" without additional software, and now that the small GL-iNet [6] router and others support DoT, it is likely to become more widespread in the small office and home office. Public DNS servers for this protocol include Google, Cloudflare, Quad9, and Digitalcourage. By the way, routing to port 853 opens up a simple option for blocking DoT on a firewall.

A better way to protect the privacy of DNS users, and one that is currently the subject of heated debate, is DNS queries over HTTPS (DoH) [7]. Mozilla Firefox version 62 and newer support this method; in the USA Mozilla has started to enable it by default. Additionally, some software packages redirect the complete DNS resolution of the operating system via DoH. The problem with this action is that your own local DNS server is no longer used, but that of a large provider such as Cloudflare, Google, or Quad9.

For the sake of completeness, DNSCurve [8], as put forward by Daniel J. Bernstein, also has to be mentioned, although it does not play a major role.

Side Effects

Until now, DNS was a service that was configured in the operating system and used by all applications. However, thanks to the efforts of web browser (Chrome, Firefox) and email client (Thunderbird) makers to encrypt DNS, name resolution is migrating to the application, where it is set up by users instead of the administrator.

In most cases, the DNS server can be configured for the operating system via DHCP. For devices over which admins have no control (bring your own device, BYOD), you can block external DNS servers on the firewall, forcing these clients to use the local DNS server. In this way, content filters (malware blockers) and DNS servers for internal resources (split horizon) can also be implemented in these cases.

However, if encrypted DNS comes into play, every option for blocking unwanted content or scanning DNS traffic for domains that distribute malware is thwarted. This is not always in the interests of an enterprise, university, research institution, authority, or the like.

A further problem for users also arises when DNS needs to run in split horizon mode; then, the DNS server handles queries differently depending on whether they come from inside or outside the local network. However, because both DoH and DoT always query an external DNS server, a user on the internal network always receives the external DNS response which means intranet pages would no longer be accessible if names pointed to different addresses on the local network, compared with externally.

On the other hand, domain names that only the internal DNS server knows are no problem. With the default settings you can tell clients to query the internal DNS server by the classic DNS mechanism if the DoH request does not return an answer. However, an experienced user could change the configuration so that their device never queries the internal DNS server. Enterprise-internal would then no longer be accessible for the user of the application with DoH.

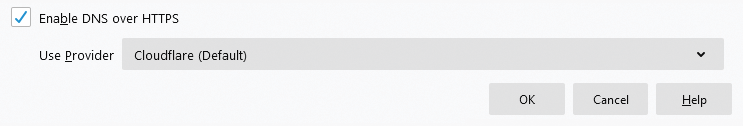

Although protective measures such as DoH and DoT make sense on public networks (e.g., WiFi in hotels or on airplanes), a university, research institute or public authority must carefully consider whether it wants to walk down that road. Currently, Firefox (version 62 or newer) and Thunderbird (version 60 or newer) support DoH, which is enabled in the settings by the user (Figure 5).

Android, which has supported DoT since version 9 "Pie," is enabled in Settings | Network & Internet by selecting the Private DNS option. The default setting is Automatic, which means that Android will use DoT if possible; otherwise not.

Google Chrome / MS Edge

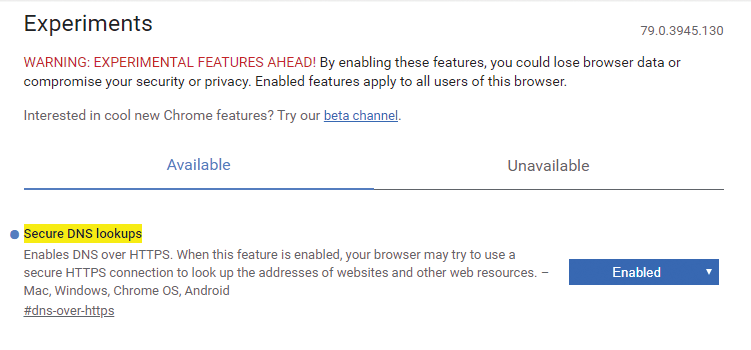

Google Chrome has offered DoH as an experimental option since version 78 (February 2018). The feature can easily be enabled in the GUI [9]. The latest version of the Microsoft Edge browser is based on Chrome, so Edge also supports DoH. The web browser contacts the DNS provider by DoH, which is configured as a classic DNS provider on the operating system side.

To do this, you call chrome://flags or edge://flags and enable Secure DNS lookups (Figure 6). As soon as one of the supported DNS servers is configured in the operating system (currently, the providers CleanBrowsing, Cloudflare, Comcast, DNS.SB, Google, OpenDNS, and Quad9 [10]), DoH is activated [11].

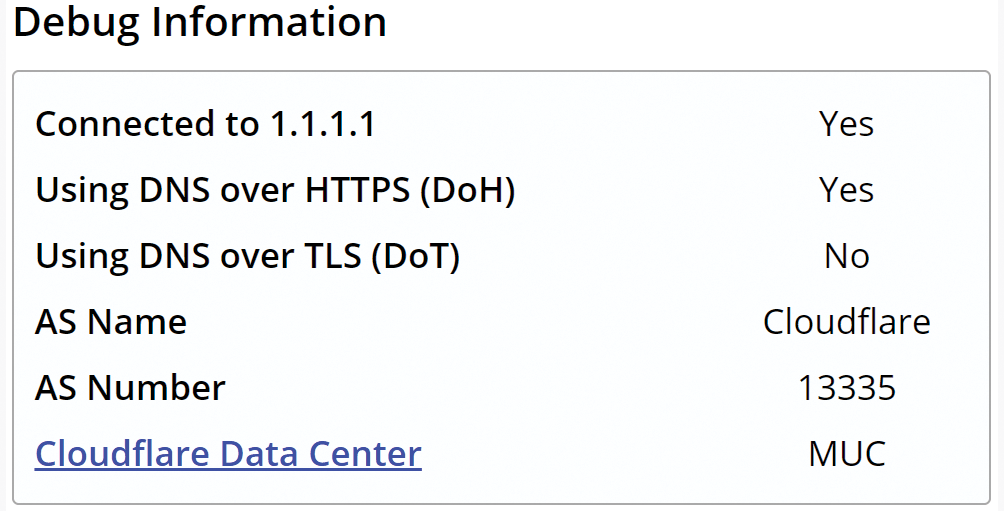

Even if the DoH option is activated, the protocol will not be used if the operating system specifies the local DNS server (e.g., at a university or research institute). However, if you configure one of the supported DNS servers in the network settings (Cloudflare in the example in Figure 7, i.e., 1.1.1.1), the browser uses DoH.

If a Chrome user can configure the DNS servers in the operating system, they can also enable DoH in this way. The only countermeasure is to block port 53 (DNS) for all internal machines except the local DNS server. In the policies, you will therefore want to set the value of BuiltInDnsClientEnabled to False [12], which keeps Chrome from using DoH, as my tests demonstrated.

Mozilla Firefox

Mozilla Firefox allows you to signal to a network that DoH is not desired. To do this, the web browser queries the use-application-dns.net domain with the operating system's DNS mechanism. If the server replies with NXDOMAIN or SERVFAIL, Firefox disables DoH.

The browser also looks for mechanisms such as Google or YouTube Safe Search and parental control filters that evaluate DNS traffic and disables DoH if it finds such software. This undocumented feature is probably based primarily on the child protection systems commonly used in the US. Additionally, deactivation only occurs if DoH is enabled by default – currently only the case in the US. However, if a user enables DoH explicitly, the user setting always takes precedence [13].

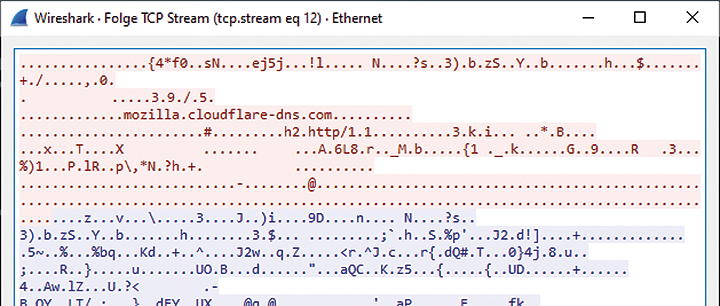

Even if Firefox uses TLS 1.3 for the DoH connection, you will see the name of the DNS server in the Server Name Indication (SNI) header when opening the HTTPS connection (the default is mozilla.cloudflare-dns.com; Figure 8). The SNI is used to tell the server with which of the hosted servers you want to communicate and is the only way in which the web server can select the certificate that matches the website.

The standard for encrypting the SNI header (encrypted SNI, ESNI) [14] is currently not used for DoH requests, because the key for ESNI has to be exchanged by DoH – a chicken and egg problem. Therefore, the default DoH provider can be blocked in Mozilla Firefox by filtering for DNS requests to mozilla.cloudflare-dns.com on the DNS server.

Potential Solutions

If a company wants to prevent the use of the alternative DNS variants, it can simply block DoT on the firewall by blocking port 853 for outgoing traffic. DNSCrypt and DoH can only be blocked on the firewall by content analysis, because they use port 443 (HTTPS).

The Internet has lists of domain names belonging to service providers that have enabled DNSCrypt, DoT, or DoH [15]. However, the number of servers is constantly increasing. Blocking access to the currently listed resources is not a permanent fix. If a server offers both DoH and one or more websites on the same IP address, blocking the IP address on the firewall is not a good solution either.

A better solution is to use the distribution/policies.json file to block the DNS settings in Firefox and Chrome. On Windows, this can be done with a group policy that also takes the portable version of Firefox into account.

With more programs or operating systems supporting encrypted DNS in the future, however, a basic solution is needed. The European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) Enterprise Transport Security (ETS) standard [16] is not suitable (CVE-2019-9191), because it seeks to read the entire traffic. Group policies cannot be used for BYOD or in education roaming, because you have no access to the settings of the computers and smart devices.

In the long run, there must be a uniform way of routing encrypted DNS queries over the corresponding corporate infrastructure in enterprise environments. Blocking the external DoH and DNSCrypt providers (both using port 443) on the firewall will forever be a hare and tortoise race and therefore does not truly offer a solution. Modern firewalls with deep packet inspection could certainly detect and block the protocols and force the use of classic DNS.

The ideal solution would be something that uses DoH in open networks but prefers the DNS infrastructure of the respective institution in controlled environments. An encrypted DNS protocol could be used for communication between the clients and the DNS server.

Conclusions

The question is, what is likely to be more meaningful for the users' privacy. The employer or provider being able to see the DNS queries, or one of the large Internet corporations seeing and most likely evaluating them? Should the DNS service be concentrated on a few large companies? How do you deal with internal DNS servers?

The combination of DoH, DoT, and DNSCrypt with ESNI and TLS 1.3 will change the use of the Internet. With these protocol combinations, Internet providers or organizations will no longer be able to block websites because the required information is no longer available. Considerable technical challenges still remain to be solved.

I recommend the following for universities and research institutions:

- Block port 53/UDP+TCP for all computers except DNS servers. This action should have been implemented a long time ago to prevent the use of external DNS servers.

- Block port 853/TCP to prevent DoT.

- Respond to requests for the canary domain use-application-dns.net [17] with NXDOMAIN.

- Use group policies to prevent DoH being enabled on managed machines.

- Set the value of

BuiltInDnsClientEnabledtoFalsein Chrome or Edge on all managed computers.

Some privacy measures that are useful for users at home and on public networks can be counterproductive for universities, colleges, research institutions, public authorities, and businesses. Especially on guest networks, malware needs to be contained, because the IP addresses used there belong to the institution. Blocking command and control systems or servers from which malicious software retroactively installs functions is a standard security measure and one often implemented by manipulating DNS.

The use of DoH at universities and in research institutions would be acceptable if the browser were to use it automatically with the DNS server(s) configured in the operating system. However, the group policies restrictions only apply to managed systems in the institution, not to BYOD devices.