Transcoding optical media in Linux

Obstacle Course

Linux has never been the first choice with multimedia users, although the free operating system offers various software for multimedia applications, including tools for collectors of video DVDs and Blu-ray discs that allow you to back up your media to mass storage devices. Backing up is recommended, because optical data carriers do not age well, and mechanical effects such as scratches or cracks can damage discs and even make them unreadable.

In this article, I look at the HandBrake and MakeMKV tools for transcoding optical video discs. (See the "Not Considered" box.)

Legal

If you want to play back self-mastered Blu-ray discs or convert them into other formats, you usually won't run into any problems. Often however, commercial discs will not play on just any old device because of integrated copy protection that restricts the reproduction of commercial optical media on computer systems. Fair Use (US) and Fair Dealing (UK) laws have allowed some form of copying, although the courts have retracted these allowances before under the influence of lobbyists [1]. In the US, ripping copyrighted works is not legal, except in a few educational cases, although the laws in other countries usually allow copying if you are backing up legally owned media or you are a single user creating versions for multiple devices (personal use exception). Wherever you reside, you should check the laws currently in effect.

Linux systems can mount these media like conventional removable media but cannot copy them in the usual way. Additionally, technical differences between video CDs, video DVDs, and Blu-ray discs require special devices to read data-intensive Blu-ray media. In this issue, I identify the applications that read and transcode these discs on Linux.

Technical

Video DVDs, Blu-ray video discs, and the now rare video CDs all have the same diameter and are optically scannable. Here the similarities end. For users, storage capacity is the clearest difference. Whereas video CDs usually have a capacity of around 700MB, video DVDs that follow the DVD-18 standard can store around 17GB. The significantly higher storage capacity not only makes it possible to offer significantly improved image quality, it also enables longer playing time. Moreover, video DVD supports the 16:9 picture format and is therefore far better suited to today's TVs and widescreen displays than the old video CD, which only supports the 4:3 format.

The Blu-ray disc outshines all of these media with a maximum storage capacity of 100GB. Not only can it accommodate very long blockbusters on a single disc, it also resolves the content in a far superior way. Movies on video CDs had a meager pixel resolution of 352x240 NTSC (352x288 PAL/SECAM), which improved to 720x480 (720x576) pixels with video DVDs. Blu-ray media, on the other hand, use Full HD resolution (1920x1080 pixels) and have many audio tracks. A successor is already waiting in the wings: Ultra HD Blu-ray, which accommodates 4K videos with up to 3840x2160 pixels.

The larger volumes of data come at a price: Blu-ray technology requires considerably more powerful hardware. A typical video CD data rate is around 1.5Mbps, with up to 10Mbps for video DVDs and a maximum of 288Mbps for fast Blu-ray drives. However, Blu-ray video discs limit the data rate to around 54Mbps.

To play high-resolution Blu-ray media smoothly, you not only need fast mass storage subsystems, but also powerful graphics cards. Because of the high data rates, the laser beams in Blu-ray drives use a shorter wavelength (405nm) than those in DVD (650nm) and CD (780nm) drives.

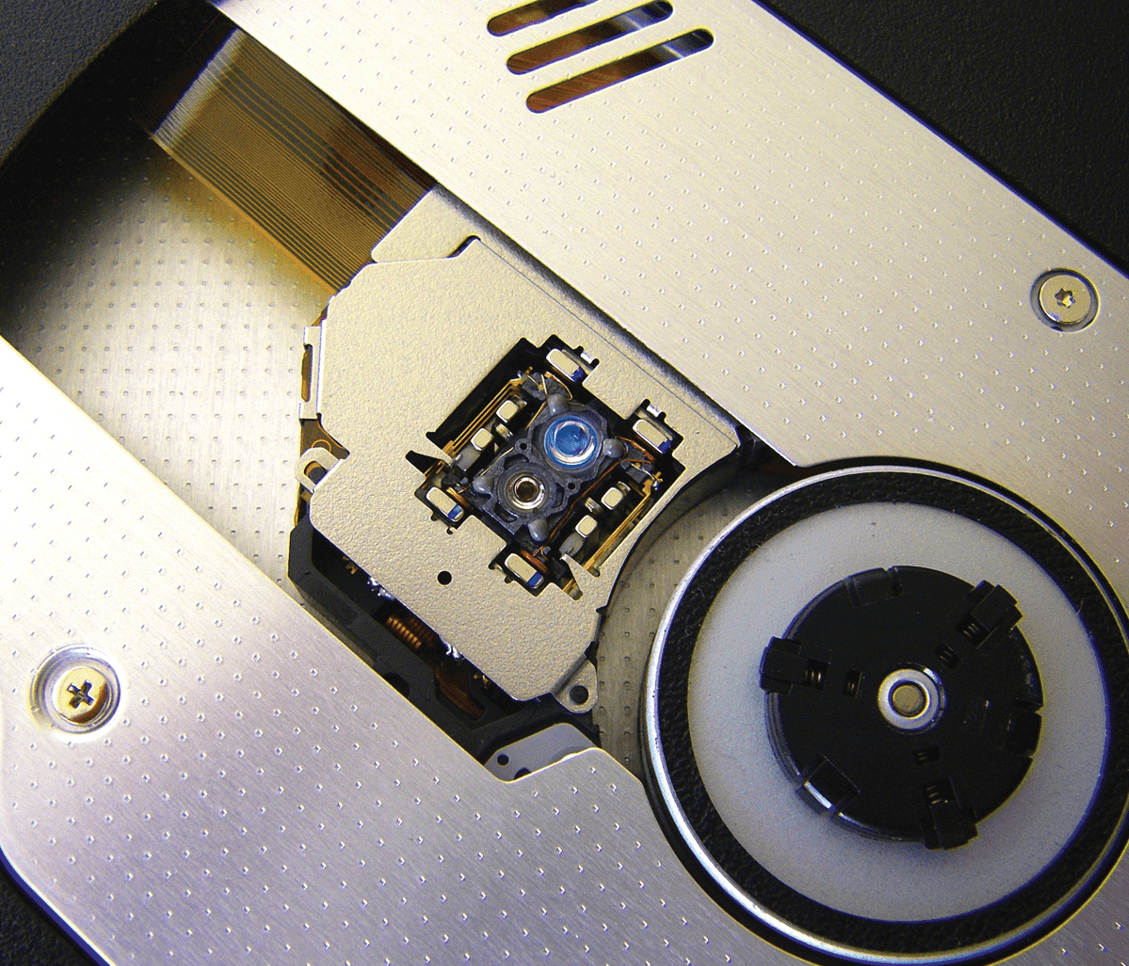

The significantly shorter wavelength of the Blu-ray lasers requires a far more complex drive structure, which makes it more expensive than a simple DVD device. For example, Blu-ray devices always have two laser diodes (Figure 1) to ensure downward compatibility. One is responsible for playing back (and recording in the case of burners) CD and DVD media; the other ensures compatibility with Blu-ray media.

Copy Protection

Commercial pressing of video DVDs and Blu-ray discs is usually accompanied by the addition of copy protection. Classic DVDs typically use the Content Scramble System (CSS), whereas Blu-ray media rely on the Advanced Access Content System (AACS) standard. The CSS system was broken 20 years ago because of numerous design flaws and weak symmetric encryption with short 40-bit keys.

To store the encrypted content stored on video DVDs on mass storage media, ripping tools first need to remove the encryption, which also applies if you want to store an identical copy of an encrypted video DVD on a recordable medium.

Additionally, commercial video DVDs also use regional codes that are intended to ensure you are only allowed to play the data carriers in question in certain countries. Some very old DVD players forced users to modify their region code settings in the firmware to play video DVDs with region codes other than the defaults.

The AACS method of HD video DVDs and Blu-ray video discs provides content with a 128-bit AES key. On the one hand, AACS introduces some innovations compared with the CSS method that make playback over networks more flexible. On the other hand, the system restricts the ability to play back on computer systems by means of drive verification with a drive-specific hardware key. If you want to play Blu-ray video discs with AACS encryption, you also need an AACS-certified drive and AACS-licensed software. These restrictions make it difficult to play commercial Blu-ray video media on Linux, because no AACS licenses exist that can be built into popular open source playback software.

As additional copy protection, all current Blu-ray players integrate the Blu-ray+ technology developed a good 10 years ago that consists of a small virtual machine that executes a Java applet. It checks whether someone has changed the firmware or the hardware-specific keys of the player. If they detect such a modification, the affected devices simply refuse to play commercial Blu-ray discs.

As manufacturers are constantly developing the process, the devices need regular firmware and key updates. The Blu-ray discs themselves also have an integrated Media Key Block (MKB) which, in combination with the other cryptographic mechanisms of the AACS system, allows content to be decrypted.

The MKB does not vary from medium to medium, but it does have version updates. To the surprise of owners, this can lead to older software variants suddenly failing with new Blu-ray media.

On Linux

Linux uses the libdvdcss program library to decrypt DVDs whose use is restricted by the CSS system. The program library is available from the software repositories of numerous distributions and can be installed with the help of appropriate package management tools. The common ripping programs on Linux will then play and transcode commercial video DVDs without any further adjustments.

The MakeMKV [5] program available for Linux transcodes Blu-ray media restricted by AACS and Blu-ray+ – without a manual installation, according to the ads. The programmers of the software indicate on their website that they always support the latest versions of these encryption mechanisms.

However, the VLC media player is all you need for simple Blu-ray playback. The HandBrake transcoding software can also handle Blu-ray with the libbluray2 package. If you want to consider menus implemented in Java on the original data carriers, as well, you need the libbluray-bdj package.

If you then install the files libbdplus and libaacs0 on your system, you are still legal, because according to the VLC website, the software does not contain any certificates or keys. The libaacs0 package only provides the encryption framework, not the actual keys and certificates.

You need these keys to play encrypted Blu-ray discs. How you can get these keys and integrate them into a Linux system is now an open secret. Various websites describe the configuration in detail and provide links to the key files, which are also regularly updated by third parties. Effective copy protection this might not be, but those in the US and European Union are nevertheless entering legally dubious territory. The VLC media player can also cope with protected Blu-ray discs, thanks to the keys, and you can use the menu in many cases.

HandBrake

For many years, the continuously updated HandBrake [6] has been regarded as a comprehensive solution for transcoding videos. The software can be found in the repositories of almost all common Linux distributions and is quickly installed without any additional overhead. HandBrake is also available as a command-line program; however, it requires some training to master the many parameters. The GUI is launched from the Multimedia menu.

The program window looks a bit confusing, with a horizontal menubar at the top and a buttonbar below it with important controls. Transcoding actions are set up in the fields below.

To begin, you have to open the source drive by selecting Open Source from the buttonbar. If you want to transcode a video DVD, the drive will normally be /dev/dvd or a data carrier already identified by the system's file manager. Blu-ray drives are usually mounted on Linux as /dev/sr0 or /dev/sr1.

Once the source has been clarified, the routine parses the individual tracks on the data carrier and automatically locates the movie. If problems occur and the application reports, for example, that it cannot find any content, check whether you have installed all the required libraries and other components for your system and whether they are up to date.

The longest track appears with a preview image in the main window. HandBrake does not automatically transcode shorter tracks, such as menu views or bonus tracks. If necessary, you can select these manually in the Title drop-down.

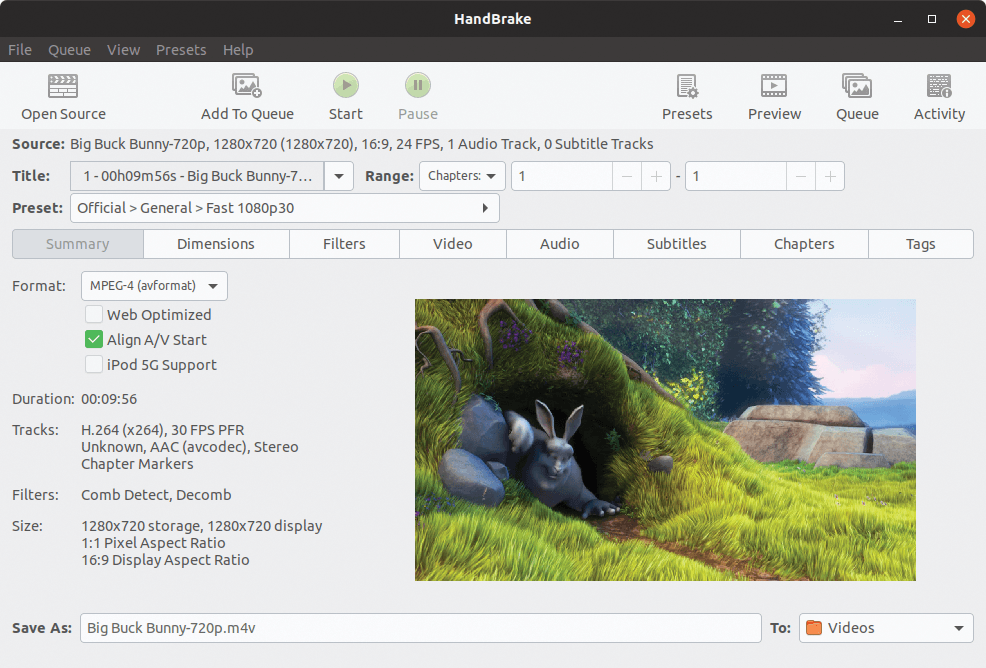

In the next step, you need to set up transcoding. HandBrake uses either MP4 or Matroska containers as the target format and offers numerous settings for both (Figure 2). You can choose UHD resolutions for Blu-ray source media for playback on high-resolution 3K or 4K monitors.

Here, you also set the refresh rate and define the compression formats you want to use (e.g., H.264 or H.265, but also VP8 or VP9). These formats can be combined with different resolutions and frame rates, if required, and you can shrink high-resolution Blu-ray media to the old PAL TV format.

Once the settings are correct, you need to identify the audio and subtitle tracks in the next step. Most movies on DVD or Blu-ray come with multilingual audio tracks and additional subtitles. In HandBrake, you select the desired audio tracks and the required subtitle tracks under the Audio and Subtitle tabs. VLC and other front ends, such as SMPlayer, let you select an audio track in different languages when playing the films. The players also show subtitle tracks at the push of a button.

From the Dimensions, Filters, and Video tabs, you can tweak further options. The choices range from modifying the image size and selecting an encoder to options for image enhancement, and you can adjust the bit and frame rates retroactively in these dialogs.

A Question of Format

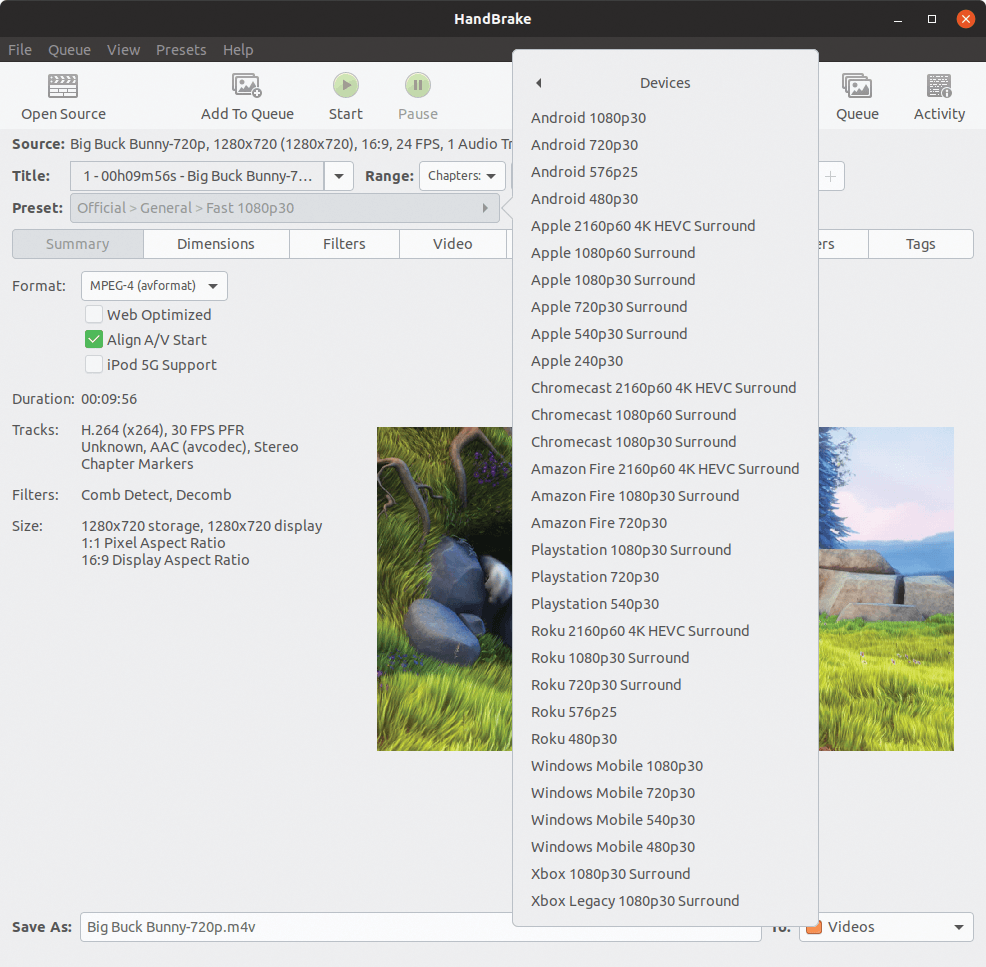

HandBrake offers an impressive number of predefined settings that are used for special playback devices such as smartphones or gaming consoles. The Preset selection field opens a submenu at the side with the possibilities (Figure 3).

The most important configurations for universal transcoding are hidden in the Matroska and General presets. The Matroska preset offers various compression formats, such as H.264, H.265, VP8, or VP9. You can choose various resolutions from the PAL TV format to HQ, as well as different frame rates. The General preset has the same nominal resolutions and frame rates but additionally offers special audio settings (e.g., for Dolby Surround). However, this dialog is defined for saving the files in MP4 containers.

The Web group has presets optimized for web applications such as Gmail and YouTube. The Devices and Legacy groups provide device-specific settings, including default settings for older devices. The range of presets in the Legacy group ranges from Apple's iPad and iPod mobile systems via Android tablets, to modern Sony PlayStation consoles, to the Xbox or Chromecast systems.

Of course, individual parameters can be changed for presets in the settings groups. However, you should be aware that higher resolutions and frame rates can have a significant effect on transcoding speed: With longer movies, it can take several hours to save them in the target format on your storage device.

Queue

If you want to rip several tracks as transcoded single files from a medium to a mass storage device, HandBrake offers the Add To Queue icon in the buttonbar. To begin, select a single track and configure the transfer. Pressing the Add To Queue button sends the job, and the matching configuration, to the list of transcoding tasks to be executed. You can view the tasks by pressing the Queue icon. If necessary, you can also remove tasks from the list.

If you want an overview of an existing task, press the Preview icon in the buttonbar. HandBrake now opens a small preview window in which it displays a short sequence of the selected track with the individual settings, so you can assess whether the configuration needs more tweaks.

Once the queue is ready, HandBrake begins processing when you press Start. The application then displays how the transcoding is proceeding in a progress bar at the bottom of the program window. The bar also shows the progress as a percentage and chronologically in real time.

Hardware

HandBrake leverages various capabilities of modern processors that address multimedia optimizations. The software supports various streaming SIMD extension (SSE) standards [7] for Intel processors, as well as the Quick Sync video processor available as of the Sandy Bridge Intel generation [8]. These settings often accelerate significantly the speed at which video formats are encoded and decoded.

If you use a dedicated Nvidia graphics card in your computer system, depending on the model, you can use Nvidia's Nvenc technology. In combination with HandBrake, this noticeably accelerates hardware encoding of H.264- and H.265-encoded videos. You can find which Nvidia GPUs work with Nvenc by checking the software documentation [9]. Note that not all Linux distributions support Nvenc, and you need to install it separately [10].

The CUDA Nvidia acceleration technology is not supported, nor for its AMD counterpart. Basically, however, HandBrake works with all common processors from the Intel Core 2 Duo generation and from the AMD Athlon X2. Because the software scales well to multiple cores, a system with four or six cores will be faster than a dual-core CPU.

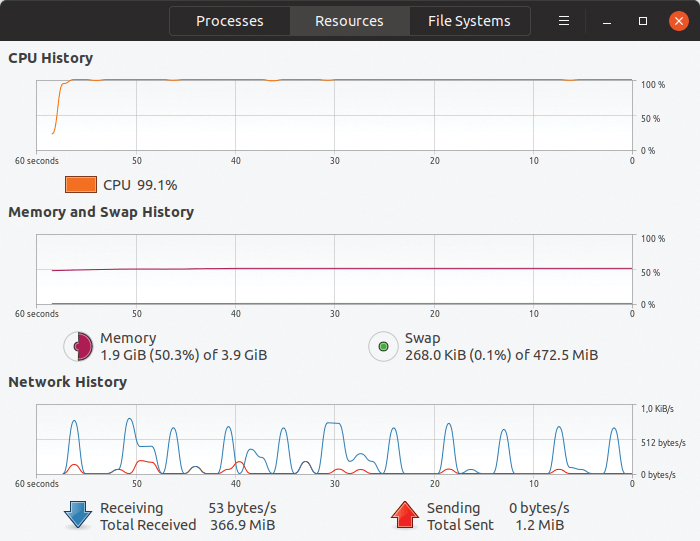

Nevertheless, processing a Blu-ray disc with a high resolution and frame rate quickly pushes older computer systems to their limits. In such scenarios, transcoding with older Core i5 or i7 processors takes two or more hours at full system load, given a normal movie length (Figure 4).

High-resolution Blu-ray media require a large amount of space, even in a transcoded state. Whereas a video DVD transcoded in PAL format usually occupies between 1 and 2GB of storage space, you have to allow between 30 and 50GB for a video Blu-ray. The space requirement can be significantly influenced by the resolution of the target file. Audio and subtitle tracks, on the other hand, do not have a major influence on the overall size.

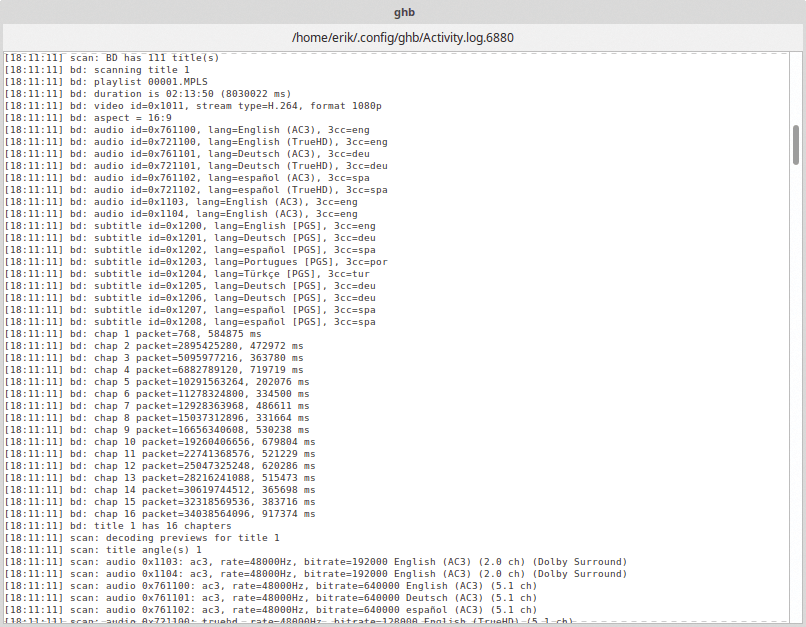

Logged

Damaged media slow down transcoding enormously from error correction runs. Therefore, it can be very useful to pinpoint problems. To this end, HandBrake offers a window with a history log, which you can access by pressing the Activity button in the buttonbar. The log (Figure 5) provides data about the original storage medium, the content, codecs, file formats, and computer hardware.

The log will indicate missing system libraries that make it impossible, for example, to include menus on the Blu-ray disc. The protocol can therefore be used to identify and eliminate the causes of errors. Another click on Activity closes the log.

If you want to interrupt the data conversion process, press the Pause icon, which toggles to a Resume icon, which you can press to continue converting.

HandBrake also reports potential storage problems when starting the transcoding process. It calculates the anticipated storage requirements for the transcoded file and compares it with the free space on the target medium. The software preempts interrupts during conversion, in which case, you should outsource existing data.

MakeMKV

MakeMKV [5] is also designed for transcoding Blu-ray discs and comprises two components: one proprietary and the other open source. The program has been under continuous development for years and can be downloaded as a beta version from the project page [11].

As a commercial product, MakeMKV requires a license key. However, the Linux version has been in beta for some time and is free of charge. The free license key is valid for 30 days and can be renewed by downloading a new key [12].

The proprietary part of the software embeds the keys it uses to decipher commercial Blu-ray discs. Because the application can convert video DVDs, it also integrates a CSS module.

MakeMKV offers fewer target formats compared with HandBrake: It supports the free Matroska container format, but not MP4. You cannot convert the original codecs with MakeMKV.

Bumpy Ride

Installing MakeMKV can be a harrowing experience. Although packages are available in the software repositories of some less popular (e.g., Slackware and PCLinuxOS) as well as popular (e.g., openSUSE and CentOS) distributions, if you are running Debian or Ubuntu, you have to compile the programs from the source. To this end, the manufacturer offers two tar.gz archives, which you install according to their instructions:

sudo apt-get install build-essential pkg-config libc6-dev libssl-dev libexpat1-dev libavcodec-dev libgl1-mesa-dev libqt4-dev zlib1g-device

Next, install the free MakeMKV archive with the usual:

./configure && make && sudo make install

In the last step, you need to change to the archive directory before adding the proprietary archive to the system with:

make && sudo make install

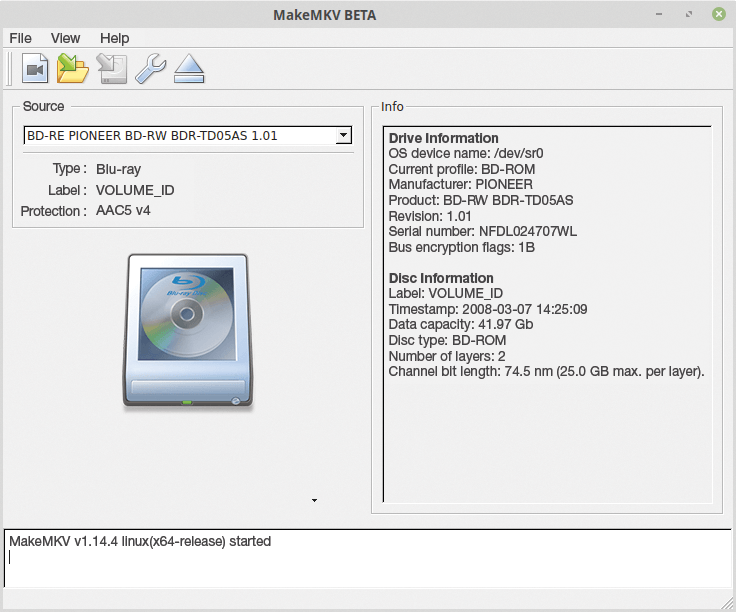

During the installation, the routine creates an entry in the Multimedia menu that lets you call MakeMKV with a single click. On first launch, you need to enter a registration key. The Help | Register menu pops up a small dialog box in which you can type the key. Keys are from the project's website and can be easily copied and pasted into the input field. After restarting the program, the software is ready for use (Figure 6).

Because MakeMKV already has the necessary requirements for reading copy-protected Blu-ray discs in its sources and integrates an AACS, as well as Blu-ray+ technology, you first have to confirm in an end-user license agreement (EULA) that you will not use the software illegally. It identifies the active optical drives in the system at startup and displays them in the main window. If the computer has several drives, you need to select the correct one.

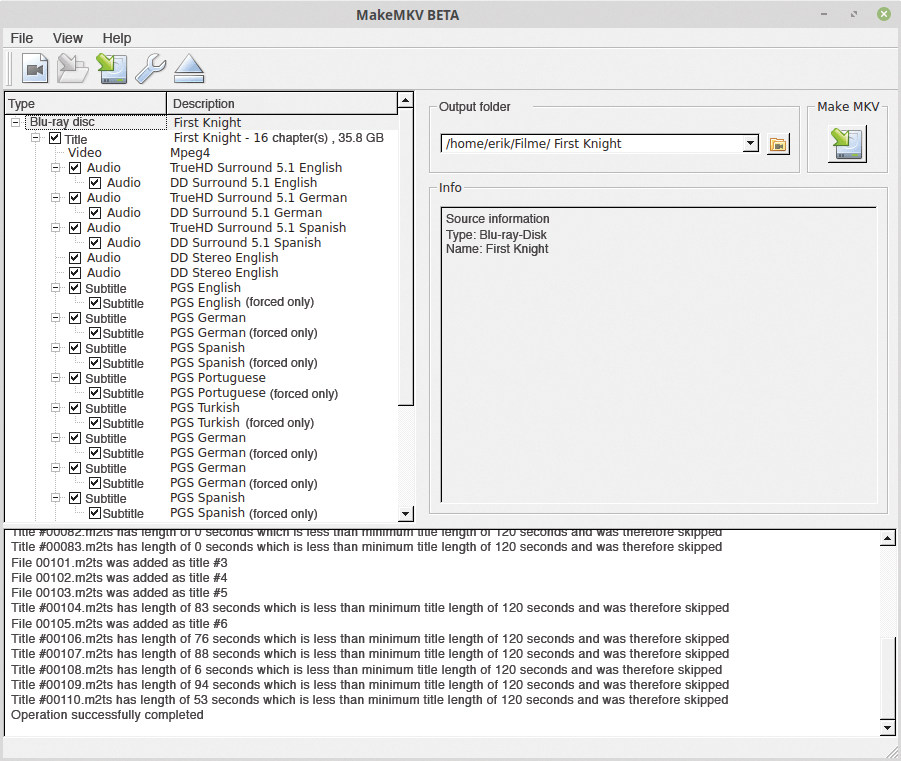

MakeMKV facilitates the selection by displaying the drive models with plaint text names, avoiding the need to guess your way through the generic block device designations. After clicking File | Open disc and selecting the correct drive in the menu, the software opens the Blu-ray disc and displays the content. On the left side of the window it checks all the detected tracks for transcoding but skips tracks shorter than 120 seconds.

In the lower part of the program window, MakeMKV displays a logfile that updates continuously. The target path and an information area appear on the right side of the window. The path for the transcoded MKV file can be modified. Click on one of the plus signs (+) beside a track on the left-hand side of the program window to open the track in question and inspect its content.

By default, MakeMKV selects all parts for transcoding. You can now use the titles to exclude unwanted content by unchecking the boxes (Figure 7). You might want to do this not only for subtitle tracks you do not need, but also for unwanted audio tracks, for example.

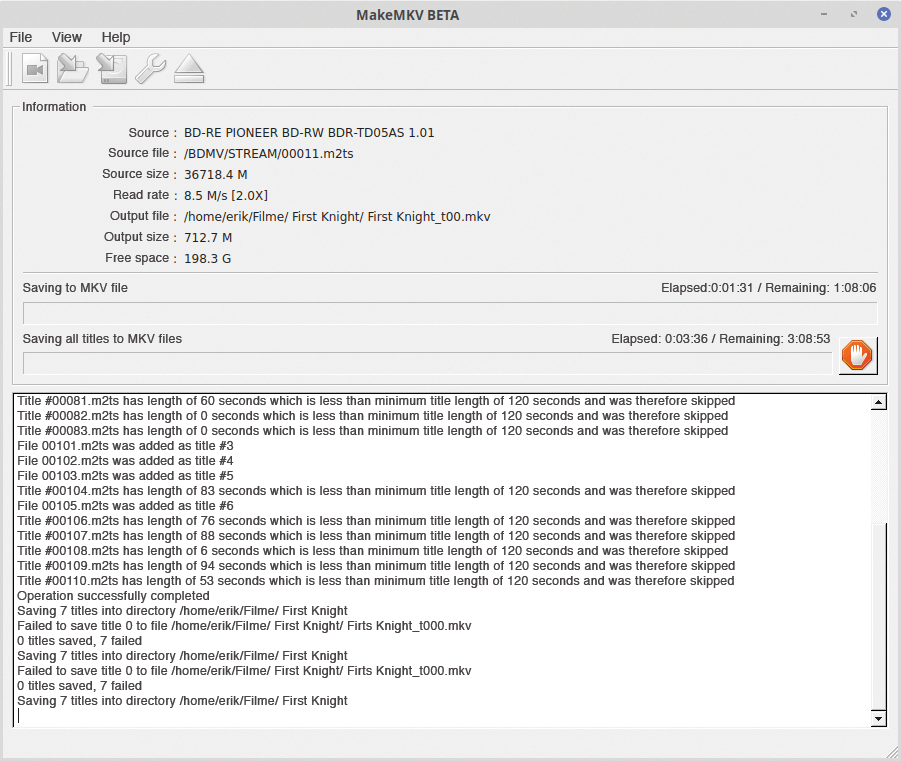

Once you have made your choice, press the Save selected titles button at the upper-right under the Make MKV icon. If the target path is still missing, the software asks whether it should create it; then, it changes to the main window. In the information area, it displays only the relevant data for transcoding (Figure 8), which includes the current space requirement.

You can track the progress of MakeMKV centrally with the two horizontal progress bars. MakeMKV transcodes the selected titles to create a single MKV container file. At the bottom of the window, you can view the history and information in the logfile.

Even with MakeMKV, transcoding Blu-ray discs takes longer than an hour per medium, but unlike HandBrake, system load is not significant, even on older hardware. MakeMKV is far better suited for laptops than HandBrake because of the lower power draw. MakeMKV does not support Nvidia's Nvenc acceleration technologies or the older CUDA, or AMD's equivalent acceleration app.

To cancel transcoding, press the red Stop icon to the right of the progress bar and confirm the prompt.

Things to Tweak

In most cases, MakeMKV runs with the default settings without problem, but if you are processing a damaged source medium that requires increased use of error correction, you can modify various software configurations accessible under View Preferences or by clicking the wrench icon. To enable more than five read attempts with bad media, increase the value for Read retry count in the IO tab. You can also modify other values, such as the target path in the Video settings.

MakeMKV can also extract the subtitle files from the source data to edit later. If you specify a path to the Closed captions extractor files in the Advanced tab, MakeMKV stores subtitles separately as subrip subtitle (SRT) files. To use this option, you first need to enable Expert mode in the General tab. Additionally, you will probably want to install the CCExtractor package [13]. For some distributions, it is available from the repositories; for others, it has to be installed manually.

Conclusions

HandBrake and MakeMKV are two full-fledged applications for Linux that support Blu-ray disc and video DVD transcoding for commercial media – if legal at your location. HandBrake is ahead in terms of functionality, whereas MakeMKV offers an easier to use interface (Table 1).

Tabelle 1: Comparison of Transcoders

|

Feature |

HandBrake |

MakeMKV |

|---|---|---|

|

License |

GPL |

Freeware |

|

Container format |

Matroska, MP4 |

Matroska |

|

Media |

DVD, Blue-ray |

DVD, Blue-ray |

|

Presets |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Device-specific presets |

Yes |

No |

|

Video codecs |

Theora, VP8/9, H.264/265, MPEG-2/4 |

Depends on source |

|

Audio codecs |

Vorbis, AC3, MP3, AAC, MPEG-4 |

Depends on source |

|

Select audio tracks |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Select subtitle tracks |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Command-line variant |

Yes |

No |

|

Hardware Support |

||

|

Nvidia CUDA support |

No |

No |

|

AMD app support |

No |

No |

|

Nvidia Nvenc support |

Yes |

No |

MakeMKV impresses with low system load and is therefore suitable for use with older hardware. On the downside, it only supports Matroska as the target container format. HandBrake lets you choose between many container formats and uses a variety of codecs. The software also offers numerous presets for special hardware, such as gaming consoles, which makes it easier to get started with the software and does not require extensive preparatory work on the part of the user. Finally, the output quality in both applications is excellent.