Logical bombs for fun and benchmarking

Explosive Code

In this column, I often make use of the stress [1] utility as a convenient way to generate load on a system's memory, CPU, or storage subsystem. Although not the most sophisticated of tools, load generators like stress are simple to use and effective, because they provide a convenient way to load a certain number of CPU cores or to fill a predefined amount of RAM and do so in a manner that can be reproduced with consistency. However, you can find other minimalist ways to generate load easily with shell commands. For example, with

shellsession $ yes > /dev/null &

the yes [2] command repeatedly outputs a string until killed and would normally be bound by the I/O speed of the terminal. Because the output is redirected into the oblivion that is /dev/null before it ever reaches the screen buffers, each such invocation is essentially a pure processor workload that will maximally use up to one CPU core while taking up close to zero I/O or memory resources.

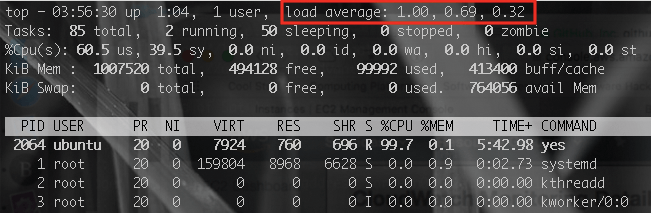

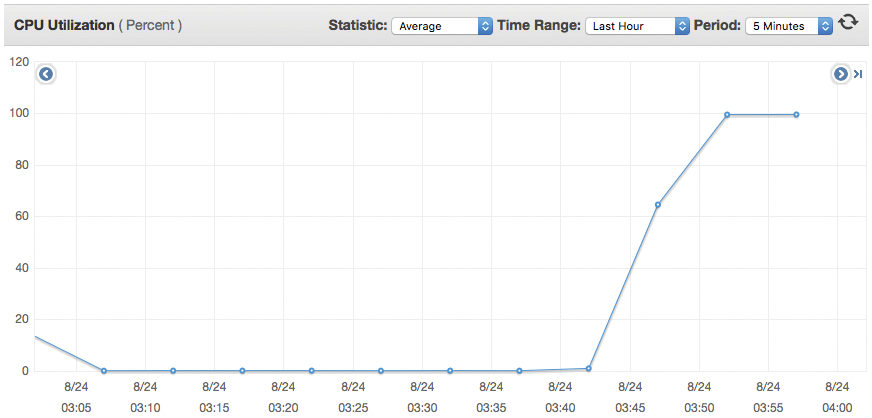

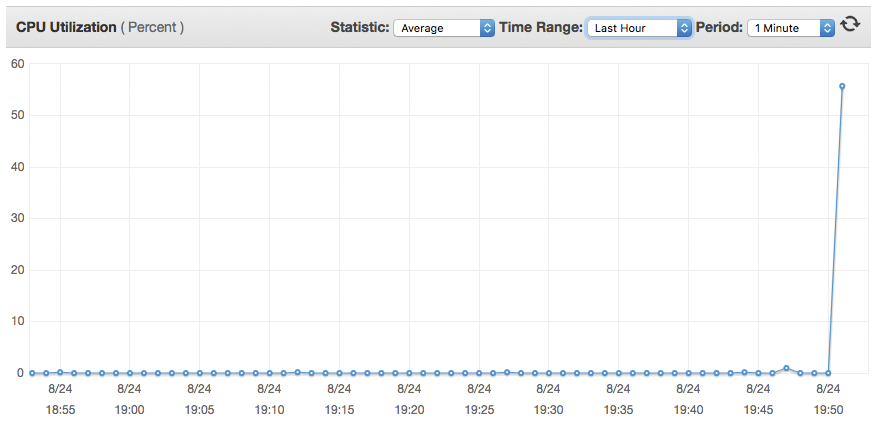

The top [3] command displays a perfect 1.00 load average after one minute (Figure 1). Amazon CloudWatch [4] data for this test instance more slowly converges on 100% CPU, consistent with the single vCPU configuration of a t2.micro instance (Figure 2).

Fork Bomb

The fork [5] command, perhaps more than any other system call, is distinctive of Unix system design. The call enters kernel space in one process, but returns in two, the original process having been duplicated into a copy. The only internal distinction between the two processes is the return value of the call itself, enabling code to distinguish the parent and child processes.

As many computer science students first learn accidentally in their systems programming class, fork and its variants can also be used to stress a system by generating a very large number of processes. A fork bomb [6] spawns so many processes so quickly that it often results in a denial-of-service attack against the machine it is running on. Once a fork bomb has been launched, it might actually be impossible to recover interactive control of the system to kill all of these processes, forcing the operator to reboot. (See the "Stopping Fork Bombs" box.)

The shell provides a straightforward way to initiate a fork bomb, in the form of a short but cryptic Bash function:

shellsession

:(){ :|:& };:

This shell scripting one-liner defines and launches a recursive Bash function named : that does nothing but execute itself in the background (twice!). This charming piece of code is best not executed on your computer, as it will likely crash it. Following that advice, I used a virtual instance on Amazon EC2 to carry out the experiment. Because the terminal session immediately froze, I used CloudWatch again to observe the CPU load shoot up (Figure 3).

RAM does not fare any better, because free memory is the limiting factor to the creation of more processes. Recovering the instance could be performed by killing all processes belonging to the user, if you could manage to log in. Fortunately, the system is watching for this situation, after a fashion.

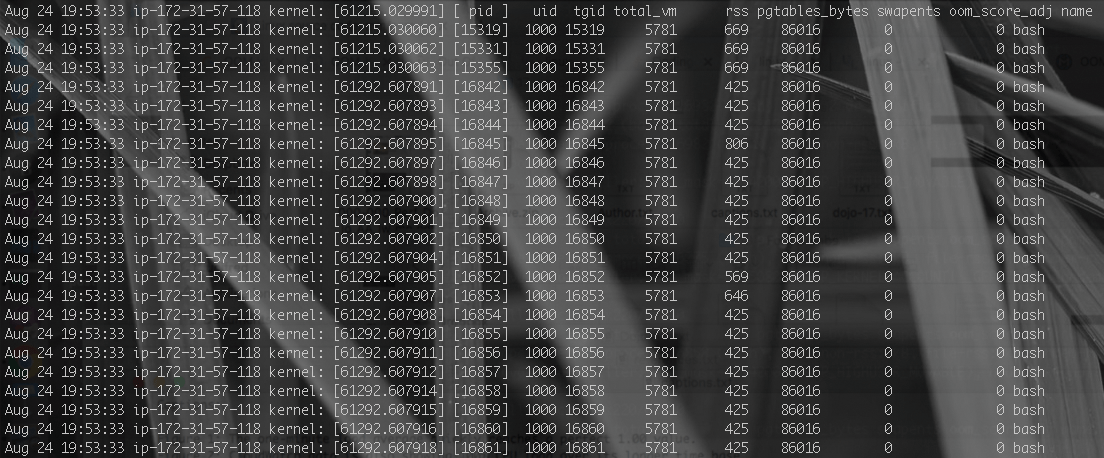

Return of the OOM Killer

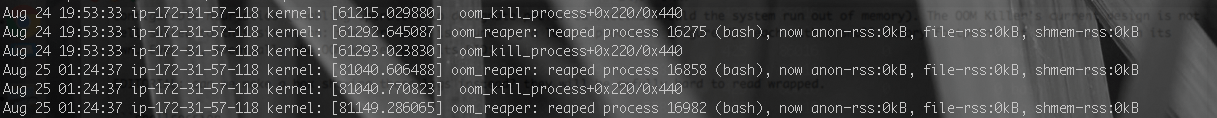

In a previous issue, I detailed the design of the Linux kernel's OOM logic [9] that went mainstream when Ubuntu 12.04 shipped version 3.2 of the Linux kernel. Processes are assigned a badness score [10], primarily based on their memory footprint, that is combined by the OOM killer with minimally configurable heuristics (enabling operators to designate preferred victims should the system run out of memory). The OOM killer's current design is not well-suited to this situation: The fork bomb is launching a lot of processes (Figure 4), each with a small memory footprint not standing out on its own. Even so, eventually the OOM killer gets its PID (Figure 5).

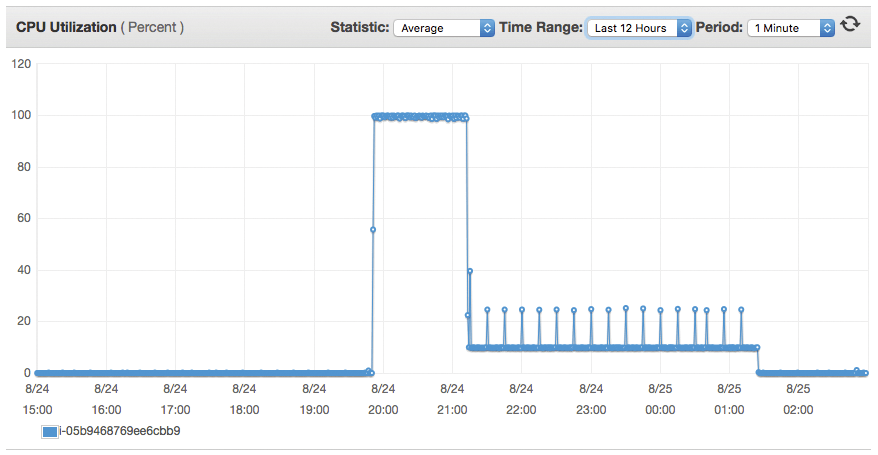

/var/log/kern.log recorded the reaper process firing three times.It did take a few tries and almost four hours before the instance returned to normal operation (Figure 6). Sometimes, you just have to get lucky! Third time is the charm, and with the third kill the system fully righted itself. Older OOM killer implementations accounted for the memory footprint of a process' spawned children (or a fraction of it), mitigating fork bombs explicitly [11], but as I read through the code, that does not appear to be the case any longer.