Troubleshooting and analyzing VoIP networks

Speechless

Because of the way people perceive speech, Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) is a transmission-sensitive application that requires certain conditions in the network. Finding and fixing network problems on Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model Layer 2 or 3 is almost trivial compared with VoIP analysis. In Internet telephony, the sources of error migrate to higher OSI Layers 4 through 7. VoIP also requires the correct interaction of all layers and thus increases the complexity of troubleshooting. Of particular importance is the end-to-end assessment of network parameters, such as available bandwidth, packet loss, delay, and jitter. In local area networks (LANs), a VoIP administrator can use a special VoIP analyzer to control the available bandwidth and the quality of voice transmission by monitoring the relevant network parameters (e.g., load, packet loss, and delays).

Effective Bandwidth

Effective bandwidth (EFB) describes the bandwidth available over the entire network path (end-to-end) at a specific point in time for the application or data flow in question. In a network, EFB is continually changing and depends on the number of simultaneous data streams. In most cases, EFB is determined by a few overloaded network connections or coupling elements. EFB is measured in bits per second (bps) and must be sufficient to transport the data successfully from the transmitter to the receiver. A deficit of bandwidth can lead to jitter and packet loss. The required bandwidth also depends on the voice codec selected.

VoIP places high demands on the available bandwidth, so you must know the network and prevailing bandwidth conditions. A VoIP analyzer displays these changes so you can see them at a glance (Figure 1).

Avoiding Packet Loss

Packet loss is the norm and occurs on every network. The packet loss rate reflects the percentage of data packets lost on a transmission path. Packet losses are typically the result of network congestion (high utilization level of the queues in routers or L3 switches) and can often be avoided by prioritization mechanisms on the network. Packet loss rates of up to five percent are hardly perceived given equidistant packet losses and non-compressing codecs. If the losses exceed 10 percent of the transmitted packets, voice quality deteriorates significantly.

The network protocols used today usually compensate for any packet losses that occur. For example, TCP retransmits a lost packet after a certain delay. However, the VoIP mechanisms and the underlying RTP/user datagram (UDP) protocols do not provide for retransmission. Packet losses must therefore be compensated (to some extent) in a different way for VoIP.

VoIP applications use packet loss concealment (PLC) to suppress the effect of packet loss. Short-term interruptions in the digital data stream can thus be bridged. The task of the PLC technology in the receiver is to generate the best possible estimate of the missing signal section and thus keep audible interference as low as possible. The achievable quality depends on several factors – in particular, the length of the lost segment, the stationarity of the speech signal at the time of loss, and the amount of information available from the surrounding speech frames. In the case of speech codecs with high compression, replacing lost speech frames is made even more difficult because the dependencies between successive frames cause errors to propagate beyond the lost frames.

The simplest PLC procedure replaces lost data with silence. More complex procedures hold the last transmitted sound or try to interpolate the sound. Older systems use waveform substitution, which fills the lost signals with artificially generated substitute signals. However, this procedure often leads to an unnatural robot voice with serious packet losses.

Newer algorithms interpolate the resulting signal gaps and achieve better sound quality. However, this is at the expense of the required computing capacities. In general, dropouts with a length of up to 30ms or a loss rate of up to 20 percent can be bridged without the receiver being aware of it. A VoIP analyzer displays the number of lost packets and visualizes them in real time. A precise root cause analysis based on the recorded VoIP packets enables the necessary measures to be taken to reduce packet losses on the network.

Special VoIP Latency

VoIP transmitted over an IP network experiences end-to-end signal delays. Delay is measured in milliseconds and is also referred to as "latency." The delay is the time interval between the occurrence of an event and the expected subsequent event. For VoIP, the delay time is the time between speaking and remote reception of the spoken message. In networks, the delay is often described with round-trip time (RTT), and round-trip delay describes the total delay (i.e., the outbound and return path between two IP endpoints). In VoIP applications, the one-way delay (from endpoint to endpoint in one direction) is important.

The delay is characterized by unwanted speech pauses or overlaps between transmitter and receiver during a conversation (echo effects). The end-to-end delay, according to International Telecommunication Union (ITU) recommendation G.114, should not last longer than 150ms. In VoIP applications, a delay that is too high results in a reduction of the quality of service (QoS).

A data stream delay cannot be determined by passive measurement. Because the packets are only recorded at one measuring point in the network, it is not possible to obtain measured values for the end-to-end delay, just for arrival time variations (jitter). A correct delay measurement always requires an active measurement on an end-to-end basis.

Cause of Jitter

VoIP packets must reach the recipient at a certain time and ideally at the same intervals. This spacing (intermediate arrival times) is determined by the voice codec. On an IP network, however, run-time fluctuation can occur or different packets can require different transmission times to cross the network. This phenomenon is referred to as jitter and is characterized by a special VoIP problem that can severely affect the quality of a telephone call (jerky communication, poor intelligibility). Jitter is the time between the target and actual arrival times. Ideally, this time difference should be 0ms. All popular IP networks have jitter caused by the transmission components.

VoIP devices use a jitter buffer to compensate for run-time fluctuations by buffering a certain number of packets. Each received packet is temporarily buffered before being forwarded to the receiver (application). The jitter buffer discards any packets that arrive too late. The control function causes additional delays in the jitter buffer. The size of a jitter buffer is either fixed or dynamic, also known as an adaptive jitter buffer, which has the ability to optimize its size to adapt to delays and data loss.

Both fixed and adaptive jitter buffers are capable of automatically adapting to delay changes. For example, if the delay gradually changes by 20ms, some packet loss results in the short term. Over this period, the jitter buffer self-adjusts and thus avoids further data loss. The jitter buffer can thus be regarded as a time window: On one side of the window (the early side), the current data is captured, and the other side of the window (the late side) represents the maximum permissible delay (after which a packet is discarded). However, the jitter buffer can only compensate for delays within certain limits. If the jitter exceeds these limits, the speech signal is interrupted.

The VoIP-only endpoints hardly contribute to jitter. The most common cause of jitter is the struggle between competing VoIP systems for limited transmission resources. For this reason, it is important to control timing with an analyzer and isolate the cause of the jitter. A VoIP analyzer performs a separate jitter calculation for each RTP stream.

Deviating Paths Cause Sequence Errors

The data and voice packets are transmitted independent of each other across the network from the sender to the receiver. Therefore, the packets are subject to individual delays, as well, even if all packets use exactly the same transmission path. However, the cause of sequence errors is usually the routing of packets from sender to receiver over different IP networks and subnets, resulting in different delay times. These path-related delays mean a small number of packets arrive late at the VoIP endpoint, which has a direct effect on speech quality and degrades the received signal. As a rule, the packets are buffered, which allows the endpoint to put the received packets back in the correct order and thus restore the original data stream.

Sequence errors are not a problem in classical data communication. The receiver arranges the data packets in the correct order by TCP sequence number and passes a correct data stream to the higher level application. Because of the real-time conditions of VoIP systems, sequence errors or problems in the transmission of voice over IP networks must be countered with a completely different strategy. Some VoIP systems discard all packets received out of sequence; others dispose of received packets with sequence errors only if their size exceeds the length of the internal buffer. This discarding of packets results in some jitter and, of course, packet loss.

Quality and Combinations of Codecs

Before a VoIP call can be made, the analog audio signal must be converted into a digital signal. Often, only narrow bandwidth is available, so some compression of the signal is also necessary. The aim is to achieve the highest possible voice quality at the lowest possible data rate. An encoding process with a low bit rate and high compression requires serious computing power for encoding and decoding. If this is not available, a procedure with a higher bit rate inevitably needs to be used.

The transmitter captures (quantizes) and encodes the speech signal as a function of the quantity. It is then transmitted over the Internet and decoded by the receiver (i.e., converted into an analog signal for playback). The most important requirement for the coding method used is that the signal must be capable of being encoded and decoded in real time – that is, with minimal delay.

"Codec" is a blended word from "coder" and "decoder" and describes a process for converting analog voice or video information to a digital, often compressed format. The methods for encoding an analog signal are manifold and have developed strongly in recent years. Higher computing capacities and higher bandwidths, especially, have improved the options for codec developers, who nevertheless still struggle with many problems. Codecs need to conserve resources on the one hand and reproduce the original signal as faithfully as possible on the other. Incorrectly transmitted or missing packets need to be replaced without affecting signal quality.

IT managers always need to consider the current network conditions when selecting codecs for the terminal devices (Table 1). For example, the use of a G.711 codec (PCM) on a narrowband connection leads to considerable delays. Discarding packets received late, classified as jitter, affects voice quality. If you only have low bandwidth (<64Kbps net and <85Kbps gross) in a transmission channel, a different codec (with higher compression and thus lower bandwidth requirement) simply has to be used; the G.729 or G.723 codecs are suitable.

Tabelle 1: ITU-T Voice-Encoding Specs

|

Standard |

Algorithm* |

Bit Rate (Kbps) |

|---|---|---|

|

G.711 |

PCM |

48, 56, 64 |

|

G.723.1 |

MP-MLQ/ACELP |

5.3, 6.3 |

|

H.728 |

LD-CELP |

16 |

|

G.729 |

CS-ACELP |

8 |

|

G.729 annex A |

CS-ACELP |

8 |

|

G.722 |

Subband ADPCM |

48, 56, 64 |

|

G.726 |

ADPCM |

16, 24, 32, 40 |

|

G.727 |

AEDPCM |

16, 24, 32, 40 |

|

*CELP, code-excited linear prediction; PCM, pulse code modulation; ACELP, algebraic CELP; ADPCM, adaptive differential PCM; AEDPCM, enhanced ADPCM; CS-ACELP, conjugate-structure ACELP; LD-CELP, low-delay CELP; MP-MLQ, multipulse maximum likelihood quantization. |

||

In practice, today's LANs and IP networks offer sufficient bandwidth in the corporate environment, and the optimal codecs will always work. In the case of external calls, bandwidth bottlenecks can occur during transition to the public network. As a rule, the bandwidth of the digital subscriber line (DSL) upstream does not match the downstream bandwidth. If a bandwidth bottleneck occurs in the upstream because of too many parallel VoIP/IP connections, the default codec G.711 must be replaced with a narrower band codec. The G.729a (CS-ACELP), G.723.1 (MP-MLQ), and G.726 (ADPCM) codecs can be used, in this case. Although they reduce voice quality, they require less bandwidth for transport.

Terminal devices negotiate the codecs when establishing a VoIP connection. The system administrator can configure which codecs the terminal devices use. When a call is established, the terminal devices involved send the supported codecs to the other end node in the form of a codec list. If multiple codecs are supported, the preferred codec should always be at the top of the list. The terminal devices check the list for the best match and then use a codec standard for the connection. If the codecs cannot be matched between the terminals, the call will not be established.

Codecs have different identifiers (RTP IDs), which are transported in RTP packets so that the station receiving the RTP stream knows which decoder it needs to use to decode the received signal. The identifiers are exchanged during signaling so that the recipients of the data also use the appropriate decoder. If you use the wrong codec, the call will not play back correctly, and all voice information will be lost.

If two terminals communicating with each other do not use the same codecs and the voice information is nevertheless reproduced correctly, then at least one media gateway must exist somewhere between the two terminals. A media gateway ensures the correct translation of the differently coded signals. This kind of a codec conversion usually affects signal quality. For this reason, as few codec conversions as possible should take place on a VoIP network.

Using the right codec improves voice quality. The analysis of the connection information with the help of a VoIP analyzer reveals problems during the negotiation of codecs, and voice quality can be improved considerably by reconfiguring the active codecs on the endpoints or gateways.

MOS Value and R-Factor

Speech quality describes the intelligibility of a human voice during recording and playback by a technical device. An assessment of speech quality is subjective and depends on the given technical means, the recording environment, the transmission path, and the environment in which it is reproduced. The evaluation of this speech quality is specified by the ITU according to the P.800: Methods for subjective determination of transmission quality standard.

The best-known method for assessing speech quality is the mean opinion score (MOS), which describes the subjective perception of a set of candidates with the help of a fixed scale for evaluating the QoS impression. However, you will not want to rely on MOS as the sole criterion for evaluating VoIP connections.

MOS values range from 1 (poor speech quality with no communication possible) to 5 (excellent transmission quality that cannot be distinguished from the original). Table 2 shows the most common codecs and the MOS value determined for each, which corresponds to the best quality a voice codec can obtain.

Tabelle 2: MOS Values of Codecs

|

Codec |

MOS |

|---|---|

|

G.711 |

4.4 |

|

G.729 |

3.92 |

|

G.726 |

3.85 |

|

iLBC* |

3.8 |

|

G.729a |

3.7 |

|

G.723.1 |

3.65 |

|

G.728 |

3.61 |

|

*iLBC, Internet low bitrate. |

|

The E-model (ITU Rec. G.107) describes a calculation for planning and evaluating the transmission quality of communication networks. This calculation model is used to determine the voice quality available to the user in a connection. The result is an objective evaluation of the transmission quality, taking into account all influencing factors. The three most important parameters of the E-model are:

- Equipment impairment factor (Ie): No unit, default value 0, valid range from 0 to 40.

- Packet loss robustness factor (Bpl): No unit, default value 1, valid range from 1 to 40.

- Random packet loss probability (Ppl): Percentage, default value 0, valid range between 0 and 20.

The E-model is a passive model calculated by a measuring system to determine the speech quality of a VoIP stream. After the parameters have been transferred to the E-model, the measuring system outputs a transmission factor (R-factor). From these values, a prediction is made for speech quality ranging from 0 to 100, which can be mapped on the MOS scale (Table 3).

Tabelle 3: R-Factors and MOS Values

|

R-Factor |

Quality |

MOS |

|---|---|---|

|

100 |

Excellent: No effort is needed to understand speech. |

5 |

|

80 |

Good: Through attentive listening, speech can be perceived without effort. |

4.0 |

|

60 |

Proper: Speech can be grasped with a slight effort. |

3.1 |

|

50 |

Moderate: Requires great concentration and effort to understand the transmitted speech. |

2.6 |

|

0-49 |

Inadequate: Despite great effort, no communication is possible. |

<=1 |

The E-model has established itself as a quasi-standard for the objective assessment of speech quality (in contrast to the subjective MOS measurement method). Because the R-factor can be derived directly from the measured values generated in tests, this value reflects the real traffic parameters. Nevertheless, a correlation with MOS values is possible. The best theoretical R-factor that can be achieved is 100, but this value does not take into account the codecs used. If, for example, a typical G.711 codec is used in a reference environment, a maximum R-factor of approximately 93.2 can be achieved. The following causes contribute to the deterioration of an R-factor:

- Codec type: Codecs with higher compression rates usually have poorer R-factors.

- Available bandwidth: Limitations of the transmission bandwidth are determined by the entire transmission system along the transmission path.

- Delays and jitter: These occur on the network and at the terminal devices and are particularly high in mobile wireless telephones because of the lack of bandwidth on the wireless network.

- Packet losses: These are attributable to physical network failures, overloaded networks, and coupling components.

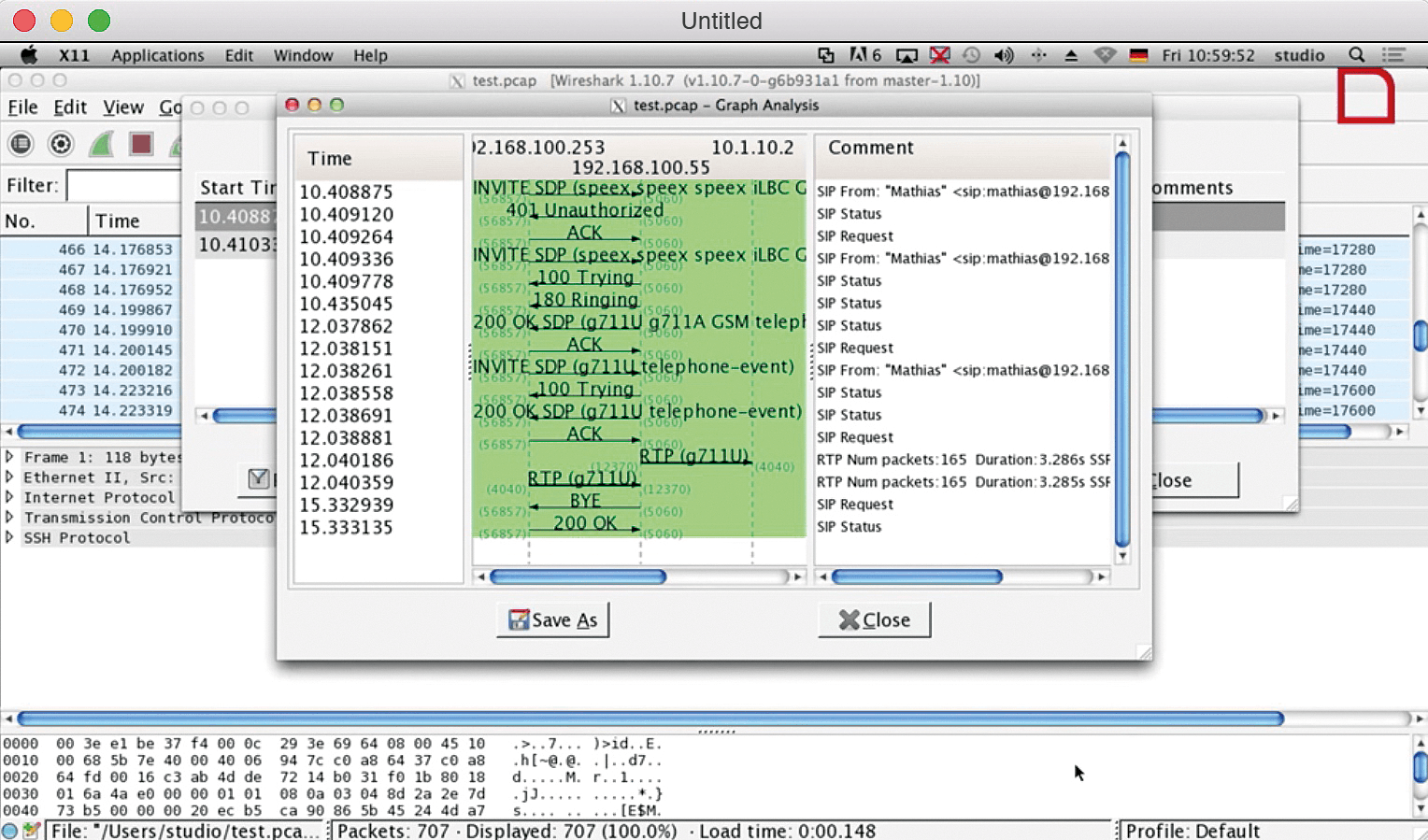

An analysis tool must therefore be able to evaluate currently recorded conversations in line with both measurement methods (Figure 2). Because the E-model is related to the packet parameters of the respective RTP session, the measurement reflects the quality of the local network segment.

Recording VoIP Connections

When monitoring the network and subsequently evaluating the signaling and voice packets, it is necessary to record the data selectively. In the analyzer, you need to pay attention to the following parameters for all recorded VoIP connections:

- Type (SIP, H.323, MGCP, or Skinny)

- Source and destination

- Start time and duration

- Status of the connection (connection setup, connection active, connection terminated)

- Initiator and counterpart

For any connection you select, the signaling of the connection can be displayed as a directional chart, and the RTP sessions belonging to the connection in question can also be listed. A packet view provides you with a detailed representation (including timestamps), the source and destination addresses, and the packet type of the recorded VoIP packets.

You can use filters to define the individual criteria that a packet must meet to be displayed. It is particularly important to ensure that the VoIP analyzer supports a wide range of different filter options:

- Connection filter: Displays the information associated with a connection (signaling and RTP data).

- String filter: Selects only packages that contain the entered string.

- IP/MAC filter: Displays only packets with the IP/MAC address specified by the VoIP administrator.

- Protocol filter: Select the different packet types for display in the protocol overview after filtering: All TCP/IP packets, TCP packets only, UDP packets only, and VoIP packets only.

Combining the filters enables even more precise selection of the desired packets.

Flexible filter settings mean that only packets or packet contents that meet the specific requirements of the user are displayed. For example, you can filter out only those packets from a data stream that contain a particular telephone number or display only the corresponding incorrect connection data by telephone number.

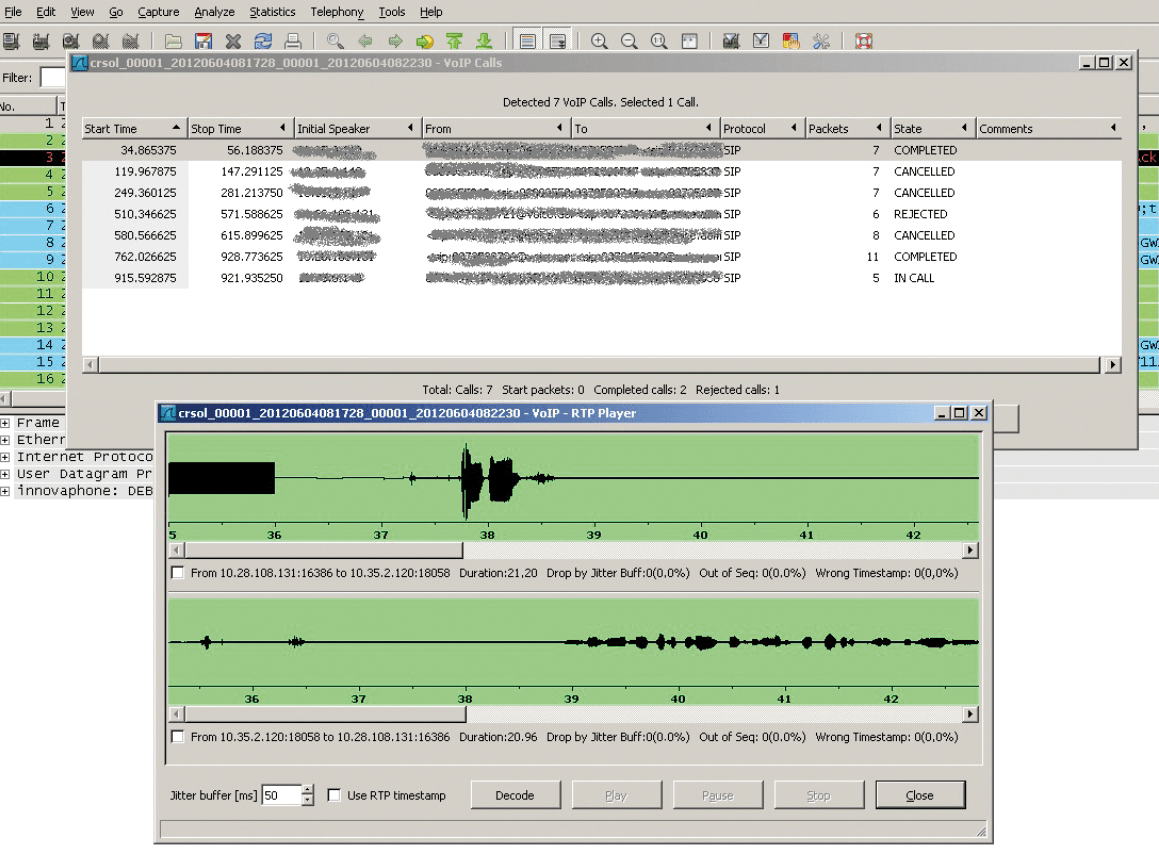

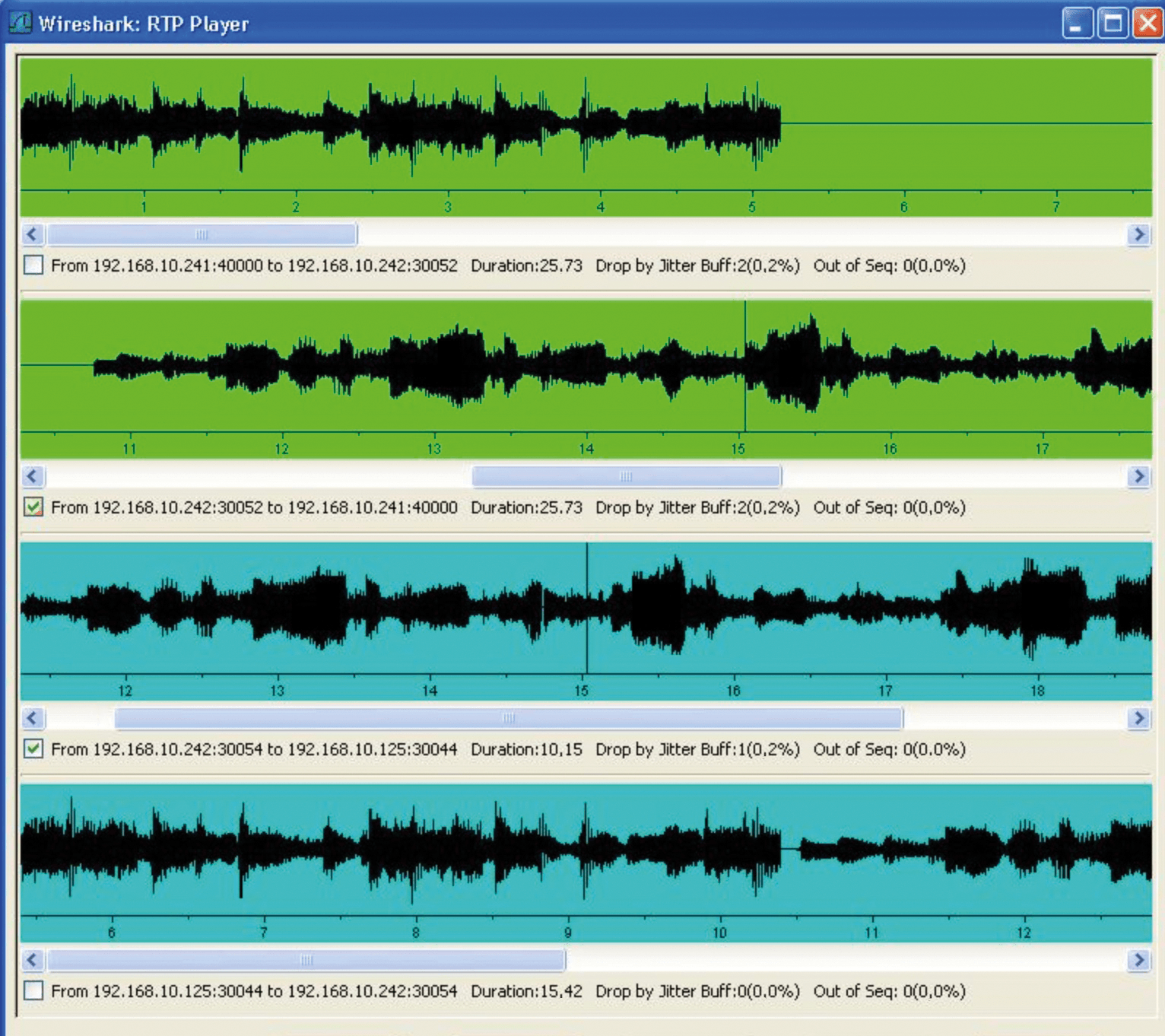

Speech Recording

The MOS value and the R-factor can be used to determine the technical quality criteria of a VoIP stream. However, to judge the transmitted language according to subjective user criteria, it might be necessary to reproduce the telephone call in question. For this purpose, a VoIP analyzer is capable of recording and playing back the transmitted speech. Letting users simply listen to the transmitted speech signals opens up the possibility of assessing genuine speech quality.

Additionally, you could decode the recorded RTP session (individually for both directions), and the error pattern lets you evaluate the session quality over the entire session duration.

The ability to display the RTP control protocol (RTCP) information for an RTCP session is also useful for analyzing transmitted data streams. The packet numbers, timestamps, absolute time, intermediate arrival time, RTCP type (i.e., sender report, SR; receiver report, RR), RTCP timestamps, packet and octet count, fraction loss, packet loss, extended high sequence received, interarrival (IA) jitter, last SR, and delay SR are displayed.

Best Practices

A few cornerstones contribute to quick problem analysis when troubleshooting VoIP networks. Targeted data acquisition is a must-have. To correctly assess a network and the applications used on it, the corresponding basic data must be available. You will want to collect the VoIP-specific data before the installation, including, for example, the number of simultaneous VoIP connections, the current LAN and wireless bandwidths, and the current and planned network loads. With this basic information, the specific boundary parameters for the VoIP network can be calculated quickly.

Furthermore, the quality and performance of the networks and applications are determined by the link components (routers, switches) on the data paths. For this reason, it is important for you to know the performance characteristics and limits of individual components. RFC 2544 defines the general test and throughput criteria that allow a subjective comparison of the products. The prioritization mechanisms used must be available throughout the components.

Because the best type of troubleshooting is prevention, you should always measure networks up front. The expected telephone volume is simulated in a realistic way, letting you discover the points on the network where improvements are still required. You will need to pay special attention to delay times, jitter, and available bandwidths. Peak loads on many corporate networks ensure that the situation can get tight repeatedly, and depending on the workload and overload, data loss can be considerable. Incorrect prioritization of real-time traffic results in delays, packet loss, and poor service quality.

In the long term, IT departments simply have to provide resources to monitor VoIP parameters actively, which means that after each extension or improvement of the network, you have to repeat the tests until the overall system meets the expectations for the required quality. Monitoring of the entire network is also indispensable. Even if a VoIP component fails, the damage can be kept to a minimum, because you can react quickly. All the parameters described in this article should be monitored on a long-term and permanent basis (Figure 3).

Conclusions

Research and troubleshooting of VoIP problems on networks are highly complex issues; casual attempts without qualified measuring tools are pointless. Today, a VoIP analysis device is an indispensable tool for troubleshooting convergent voice and data networks. However, even purchasing the best device does not mean you can sit back and relax. If you do not have an understanding of the special issues of voice transmission over the Internet, as discussed here, even technically impeccable troubleshooting will be in vain.