Arm yourself against cloud attacks

Stormy Weather

If your clients lose confidence in your ability to operate a system well and securely, you can experience considerable financial losses, especially after a successful large-scale attack. In the worst case, you could find yourself on the wrong end of a lawsuit if the question of gross negligence is raised.

None of that changes in the cloud. Admittedly, unlike conventional setups, the challenge is no longer unique to the provider. All stakeholders share the responsibility for security: From the perspective of the platform, admins ensure that standards (e.g., meaningful network segmentation, software-defined networking (SDN), security policy enforcement, and other functions) are implemented and work as desired to provide security at the platform level. When rolling out their own applications in the cloud, customers and external service providers also ensure that they comply with security best practices.

However, what are these best practices in the context of the cloud? How do customers and external service providers protect their virtual environments from the vast array of attacks that can occur? How do they even find out that something is wrong? Many conventional solutions from the past no longer work in clouds, so the question arises: Which approaches and tools are available to let admins thumb their noses from the outset at potential crooks? In this article, I slip into the perspective of a cloud customer and investigate precisely these questions.

What Is the Threat Scenario?

If you are familiar with security in the IT context, you will be aware that the first relevant question always relates to the threat scenario you want to counter. The answers result in individual safety solutions which, in the worst case, do not share any common components. If you want comprehensive security, you can't avoid this groundwork. Cloud customers have more than enough threat scenarios with which to deal.

This process starts with the choice of platform. Where does the company to which one entrusts one's own data have its registered office, and to whom does it have to grant access to its customer data by law? Does the vendor follow current best practices at the hardware level, and can they prove it (e.g., with corresponding certificates)? Which cloud software does the provider use? Does the provider keep it up to date?

Once the customer has chosen a vendor, the next question is what features they are offered in their platform to enhance security. Do they have an option for installing firewall rules at the platform level? Do they have features like VPN as a Service or other solutions with security relevance? Can they encrypt volumes?

Next is the huge selection of software which the admin can install directly at the virtual machine (VM) level: Classic honeypots are just one example. Finally, another type of threat can also be a real problem: manipulated billing data. How can a customer measure what they are actually using to have a remedy against apparently false invoices?

Protecting Critical Data

One crucial question on the way to the cloud is the question of trust in the provider. It is particularly convenient to simply lease resources from one of the major providers – AWS, Azure, and Google's cloud platform. One of the largest slices of the global cloud cake is currently in the hands of Amazon AWS, and every single day, Amazon expands its portfolio, adding several more as-a-service features.

For years, AWS customers have not operated components such as databases or load balancers themselves; rather, they use as-a-service applications. AWS is comfortable, AWS is stable and reliable, and, moreover, AWS is comparatively inexpensive – so you might think everything is okay.

However, it's not that easy after all. Amazon, Microsoft, and Google are US companies that are primarily governed by US law. Assurances that data are not released on servers in other countries do not help. If the FBI or the CIA knock on the doors at company headquarters, US companies will usually (have to) cooperate. Microsoft actually went to court several times in the US and was forced to cooperate [1].

Moreover, as a cloud customer of AWS and like services, you effectively have no chance to defend yourself against data sniffing by third parties because it is difficult, or even impossible, to provide meaningful protection for a system to which a potential attacker has physical access in the event of an attack. Although encrypted volumes are a tool of choice, they hardly help. As long as they are active and mounted, anyone with access to the hardware can read them without the customer noticing.

If you put your data in the hands of cloud services, you are forced to play the game by their rules. At least for critical data, such as trade secrets, use is therefore forbidden – you simply have no way to protect yourself effectively.

What Is a Good Provider?

Fortunately, AWS, Azure, and Google are not the only active providers of public clouds. T-Systems, with its Open Telekom Cloud, operates its cloud exclusively in Germany and is therefore only subject to German data protection guidelines. Other providers also vie for the favor of users. The only question is: How does a customer know that their cloud is well maintained? The somewhat sobering answer is: They cannot. That said, indicators exist from which conclusions can be drawn.

If you are a customer of a cloud platform yourself, you need to pay meticulous attention to the certificates the provider presents. However, certificates usually don't say anything about whether a cloud is genuinely secure; they just state the extent to which the provider's processes are standardized and documented and reflect the best practices of the respective certifier.

ISO 27001, which provides the "requirements for establishing, implementing, maintaining, and continually improving an information security management system within the context of the organization" [2] may be familiar to many people from their own business experience. SOC2 C5 [3] from the German Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) also demonstrates fundamental processes. The Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) [4] is far more extensive, with certification correspondingly more difficult to achieve.

The usual provisos apply: If a vendor can provide any certificates at all, in each case, they have had their platform audited in line with the applicable rules and passed the audit. When in search of a cloud provider, such certificates are a useful indicator (Figure 1).

![Certifications – here from BSI – do not certify security, but standards that enable security. Source: Cloud Computing Compliance Controls Catalogue (C5) [5]. Certifications – here from BSI – do not certify security, but standards that enable security. Source: Cloud Computing Compliance Controls Catalogue (C5) [5].](images/cloud-security_1_ENG.png)

Basics in the Cloud

After choosing a provider, the next step is usually to set up the basic virtual environment in which you will be operating your services. A few basics should be considered that allow implicit security and are based on the assumption that caution is better than indulgence.

Unfortunately, you can still see public cloud setups today that admins have simply and stubbornly copied from conventional environments into the cloud. Although not totally reprehensible, it does kill most of the benefits that users want to leverage when switching to the cloud.

Virtual environments in the cloud ideally have as little persistent data as possible. On one hand, admins can achieve this through a high degree of automation – preferably through orchestration, which every modern cloud offers. On the other hand, consistent implementation of a functional continuous integration/continuous delivery environment can create VMs or containers in a completely automated process.

In concrete terms, this means that if a VM or a container in a cloud has to be updated, an automatic process ideally creates a new VM or builds a new container that then replaces the old instance, almost without downtime; the admin does not need to worry about manually tracking the versions of individual systems.

It is also useful if a setup can be rebuilt out of the box in a few minutes by orchestration and automation, so that only the data (e.g., in a database) needs to be reloaded on completion. Such a system demonstrates effective, living, state-of-the-art security that helps eliminate problems caused by outdated software.

Use Firewalls

Of course, such a setup does not release the admin from keeping an eye on security basics. As on physical systems, it is a good idea in clouds to protect your own setup against attackers (e.g., by deploying firewalls). However, you need to keep in mind that networks in clouds work in a somewhat different way than in conventional setups. In clouds, the VMs or containers are never directly connected to the Internet.

To achieve the goal of central manageability and save resources, clouds instead use network nodes to redirect network traffic. Depending on the SDN setup, every node in a cloud can also be a network node and does not initially change the way traffic is redirected.

Conceivably, you could now store your firewall rules directly on the VMs, thus more or less working around the cloud. However, this choice deprives the admin of the API-controlled management tools that most clouds offer and instead requires establishing the corresponding firewall rules at the platform level.

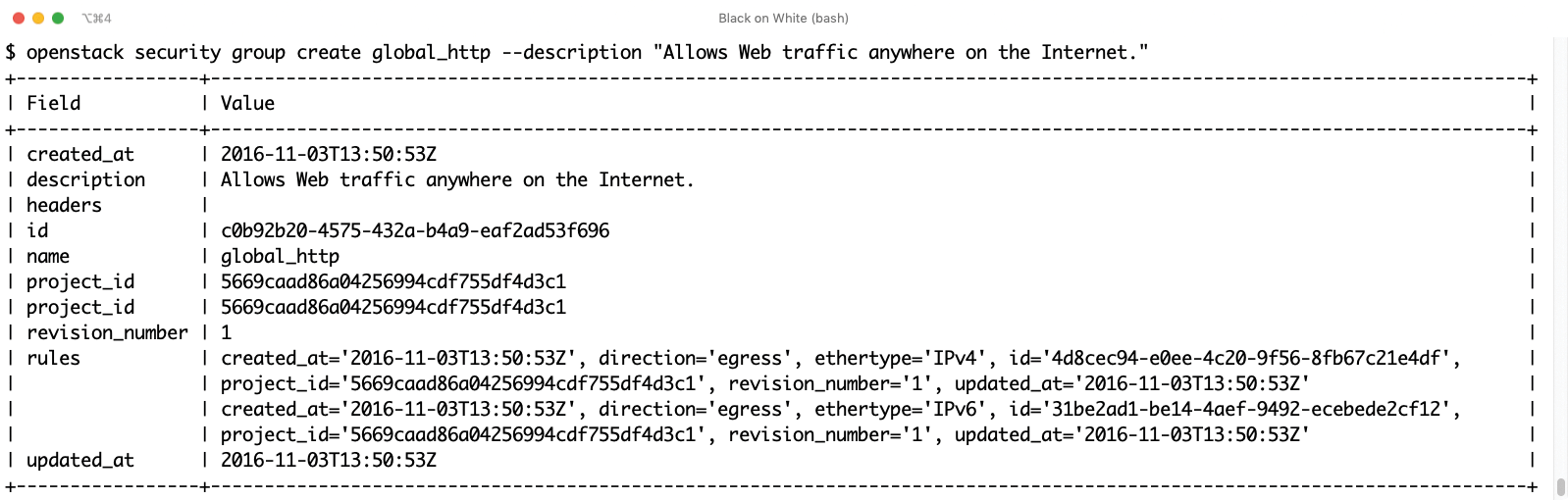

In tech speak, this is normally known as a security group: Each virtual network port is connected to at least one security group, and for each group, the admin determines which access rules apply. The cloud then converts these rules into Netfilter instructions and enables them at the right place in the (physical) underlay.

Admins are well advised to build a functional security group configuration for their virtual environments once only and then convert it to a template for the platform's orchestrator (Figures 2 and 3) to allow the rules to be recycled at any time and even modified from the outside.

Conveniently, if an attacker manages to break into the virtual environment, by whatever means, the firewall rules still apply. The attacker cannot open port 22 to the outside by deleting the corresponding Netfilter rule to gain access to the system by SSH.

How security groups can be used in AWS is explained in an Amazon document [6], and OpenStack provides a manual [7], as well.

The Trouble with IDSs

Some admins might be used to working with intrusion detection systems (IDSs) in their conventional setups. For the reasons mentioned above, however, these cannot usually be used ad hoc in a cloud. In a bare metal setup, admins usually configure IDSs so that one port on the switch mirrors and evaluates all the traffic from all the other ports. The traffic therefore does not pass through the IDS before it reaches the target systems.

Such a setup cannot be implemented in clouds because of the network nodes mentioned earlier: Users usually have no access to them. If users still want to operate an IDS in a cloud, they need to rely on the cooperation of their cloud providers. If you are using an SDN solution such as OpenContrail, you might be able to use virtual network functions (VNFs) in your own virtual environment. In practice, the user then stores an operating system image with the Suricata project administrator manager in the cloud's image store and then starts a VNF instance based on that Suricata image.

How VNFs are implemented differs greatly between the individual SDN implementations. What almost all environments have in common, however, is that direct access to the virtual packet router is not possible. A cloud provider that does not offer VNF functionality leaves the customer whistling in the wind.

Security Appliances

Caution is also advised before the customer buys a cloud appliance that includes features such as an IDS, supposedly out of the box. One prominent player in this market is Kaspersky, which wants to bring its hybrid cloud security product to the people. In principle, the product description looks good: Anyone pursuing a hybrid cloud concept should be able to use the product to protect their own cloud and their own data reliably against attacks in a large public cloud.

The Kaspersky product contains an IDS and an intrusion prevention system (IPS), as well as various other functions that enable network traffic control and blocking. What Kaspersky actually does is more likely bundle various components into a finished product that can be rolled out and used quickly in the style of an appliance.

Nevertheless, caution is advised with such offerings, because such providers often define the cloud differently from Amazon. Kaspersky, for example, does not have OpenStack, the most widely used open source solution for cloud environments. The assumption is that the customer's private cloud is based on products such as VMware and that AWS, Azure, and others are used as the public cloud.

McAffee offers a public cloud server security product, with the option of connecting to OpenStack with a connector module, along with features such as intrusion detection.

However: If the platform supports VNF features out of the box, they can be deployed manually without detouring through a proprietary solution. A customer must ultimately decide whether to pay a vendor money to reduce the workload for implementing the cloud, although there is no technical reason to do so.

Encrypted Volumes

The previously mentioned encrypted volumes make a small contribution toward data security. Volume snapshots can also be encrypted in most cloud environments so that data stored there is protected against third-party eyes or fingers.

With a volume in use, however, it is not so easy: During operation, the volume must be mounted in the filesystem and usually has to be writable, which translates to decrypted.

By the way, if you store backups of your environment in an object store, be it Amazon S3 or a private store (e.g., Ceph), you will want to use the encryption function in your backup software. Almost every modern backup program offers matching features, but thus far, too few admins are aware of this fact.

Caution with Pen Tests

As already mentioned, a cloud can have several levels of security under the microscope. On the one hand is the bare metal and the APIs that belong to the cloud – the provider is responsible for these. The VMs of the customers, for which they are responsible, run on this infrastructure. Usually the transfer point is the single VM and, more specifically, its Linux kernel.

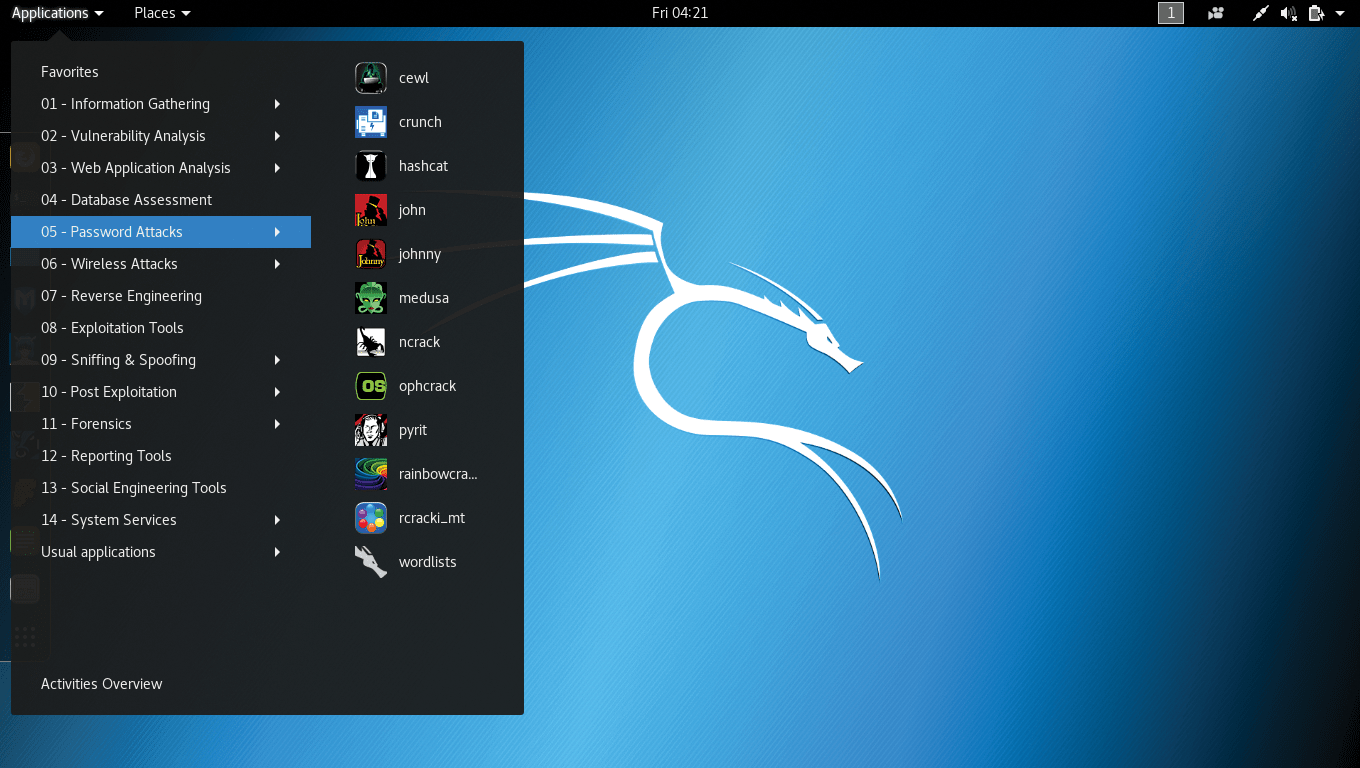

If you have built a setup and want to put it through its paces or see how a cloud is doing in terms of security, you can always use Kali Linux. In recent years, the distribution has made a name for itself as a system specializing in penetration tests (Figure 4).

If you want to run Kali Linux on hardware, you usually need a fairly powerful system. However, this contradicts the concept of the cloud, which is intended to free customers from any need to keep hardware in stock. Therefore, the distro has established itself in recent years as a method of conducting pen tests from a VM in the cloud.

At times, so many admins have done this that the big public clouds almost came across as botnets – Kali Linux, for example, runs various (heavy) attacks against the infrastructure. If a Kali Linux instance falls into the wrong hands, it can be combined with the power of virtual instances to cause trouble in the cloud.

For this reason, all major public cloud providers strictly specify whether and under what circumstances Kali Linux can be run in a VM on a platform. For example, AWS requires the password-based login to be disabled for Kali Linux VMs, so only SSH key login to a VM is possible.

Furthermore, and it should go without saying, it is illegal to use Kali Linux for purposes other than performing a penetration test on your own environment. Users are well advised to follow the basic rules of the cloud providers, because in the worst-case scenario, it can mean the end of your cloud account. One thing is still true: If you follow the rules set by the provider, you will find Kali Linux a powerful tool.

The Tiresome Subject of Billing

A final threat scenario in the cloud is less a concrete technical threat and more a commercial one: How does a cloud customer avoid being overcharged? After all, all providers promise "by-the-minute billing" and billing exclusively for resources used.

At least in the standard situation, you are dependent on trusting the figures shown in the invoice because the systems in the cloud, which collect all user data, are usually inaccessible to the customer. How can you protect yourself effectively and efficiently against abuse of accounting sovereignty?

The answer is as simple as it is frustrating: you can only protect yourself effectively if you take your own measurements and regularly compare them with the provider's figures. Slight differences are unavoidable, but major differences will quickly be noticed and allow you to ask the provider for further information.

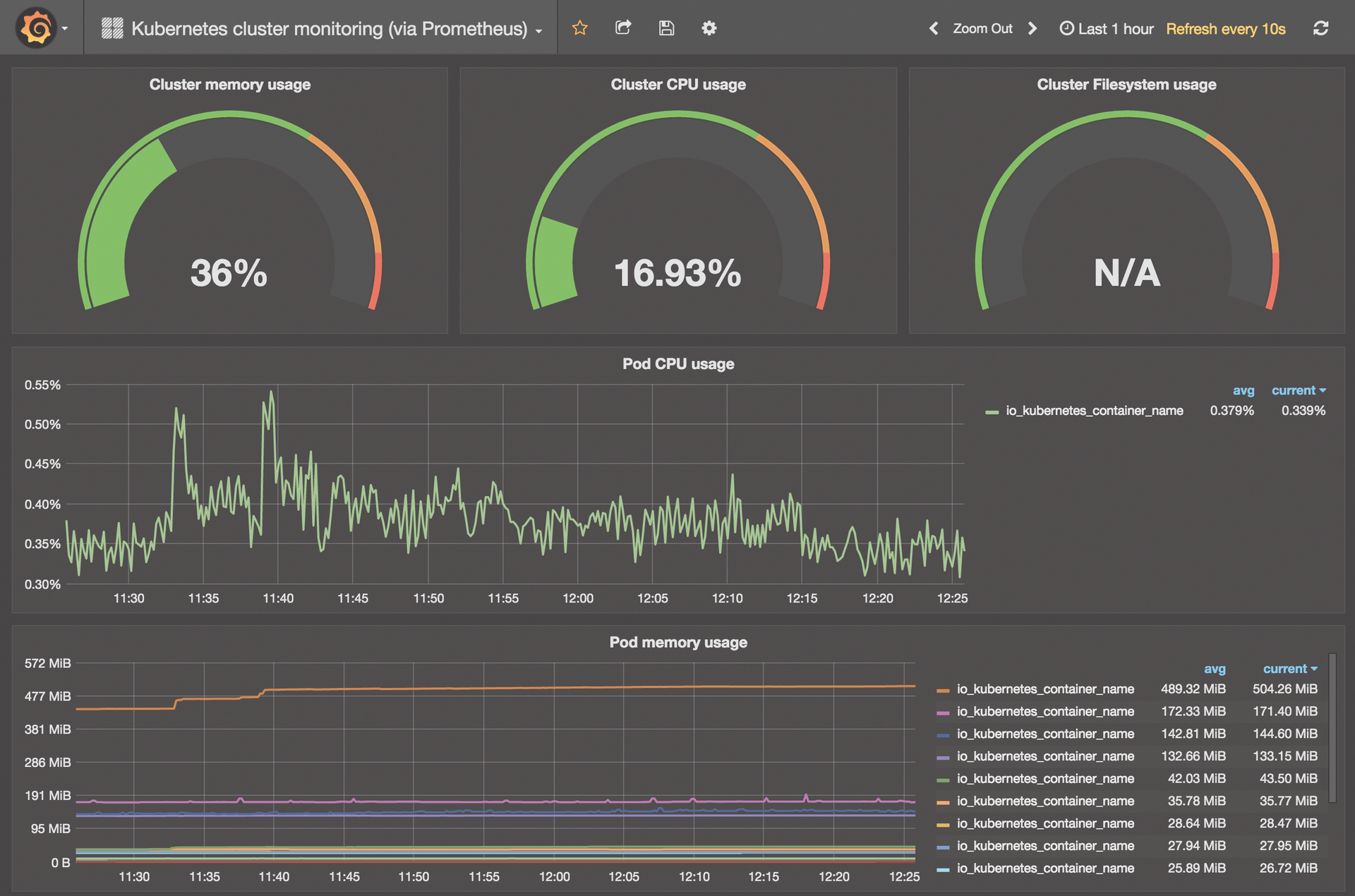

Unfortunately, only those who use software like Prometheus or InfluxDB, which can process the time series data and store it for a long time, can perform these measurements. Additionally, software is needed to collect metric data on the target systems – and both together can cause some administrative overhead.

At the end of the day, images and containers with Prometheus and like monitoring tools exist and can be put into operation quickly in all environments. Rolling out the Prometheus Node Exporter or TICK Stack Telegraf is also easy. The reward for all this effort is a reliable database that allows you to detect inconsistencies quickly (Figure 5).