Turning machine state into a database

Inquiring Mind

In the best tradition of BYTE magazine's Chaos Manor [1], I decided to write a column entirely different from what I had planned just three days before its due date. This change was occasioned by the Linux Foundation's recent announcement [2] of yet another open source foundation, this one tasked with steering the development of a really under-appreciated tool named osquery [3].

The announcement reaffirms support for the project from Facebook, Google, and Boston-based osquery vendor Uptycs, among others, and seeks to establish vendor-neutral Linux Foundation governance. It should be noted that osquery itself was already open sourced by Facebook way back in 2014 [4]. Governance aims aside, the announcement highlights a clear desire to drive more attention to a unique tool that has so far successfully evaded its well-deserved spot in the limelight.

A Successful SQL

SQL [5][6] is perhaps the oldest standard in our industry that remains still relevant, but it is not usually associated with monitoring system state. Osquery encapsulates the state of the system as a relational database and then allows users to use SQL queries to explore this data from any angle. The results can be tailored to extremely specific aims. For example, the following query lists running processes whose executable image has been deleted, the likely marker of a malware infection:

shellsession osquery> SELECT name, path, pid FROM processes WHERE on_disk = 0;

Osquery version 3.3.2 running on an Ubuntu 18.04 "Bionic" test setup describes the full system state in 131 database tables, ranging from processes and their details, to installed packages and subscribed repositories, to anything in between (Table 1).

Tabelle 1: Tables Available in osquery 3.3.2 on Ubuntu 18.04.02

|

acpi_tables |

|

apt_sources |

|

arp_cache |

|

augeas |

|

authorized_keys |

|

block_devices |

|

carbon_black_info |

|

carves |

|

chrome_extensions |

|

cpu_time |

|

cpuid |

|

crontab |

|

curl |

|

curl_certificate |

|

deb_packages |

|

device_file |

|

device_hash |

|

device_partitions |

|

disk_encryption |

|

dns_resolvers |

|

docker_container_labels |

|

docker_container_mounts |

|

docker_container_networks |

|

docker_container_ports |

|

docker_container_processes |

|

docker_container_stats |

|

docker_containers |

|

docker_image_labels |

|

docker_images |

|

docker_info |

|

docker_network_labels |

|

docker_networks |

|

docker_version |

|

docker_volume_labels |

|

docker_volumes |

|

ec2_instance_metadata |

|

ec2_instance_tags |

|

elf_dynamic |

|

elf_info |

|

elf_sections |

|

elf_segments |

|

elf_symbols |

|

etc_hosts |

|

etc_protocols |

|

etc_services |

|

file |

|

file_events |

|

firefox_addons |

|

groups |

|

hardware_events |

|

hash |

|

intel_me_info |

|

interface_addresses |

|

interface_details |

|

interface_ipv6 |

|

iptables |

|

kernel_info |

|

kernel_integrity |

|

kernel_modules |

|

known_hosts |

|

last |

|

listening_ports |

|

lldp_neighbors |

|

load_average |

|

logged_in_users |

|

magic |

|

md_devices |

|

md_drives |

|

md_personalities |

|

memory_array_mapped_addresses |

|

memory_arrays |

|

memory_device_mapped_addresses |

|

memory_devices |

|

memory_error_info |

|

memory_info |

|

memory_map |

|

mounts |

|

msr |

|

npm_packages |

|

oem_strings |

|

opera_extensions |

|

os_version |

|

osquery_events |

|

osquery_extensions |

|

osquery_flags |

|

osquery_info |

|

osquery_packs |

|

osquery_registry |

|

osquery_schedule |

|

pci_devices |

|

platform_info |

|

portage_keywords |

|

portage_packages |

|

portage_use |

|

process_envs |

|

process_events |

|

process_file_events |

|

process_memory_map |

|

process_namespaces |

|

process_open_files |

|

process_open_sockets |

|

processes |

|

prometheus_metrics |

|

python_packages |

|

routes |

|

rpm_package_files |

|

rpm_packages |

|

selinux_events |

|

shadow |

|

shared_memory |

|

shell_history |

|

smart_drive_info |

|

smbios_tables |

|

socket_events |

|

ssh_configs |

|

sudoers |

|

suid_bin |

|

syslog_events |

|

system_controls |

|

system_info |

|

time |

|

ulimit_info |

|

uptime |

|

usb_devices |

|

user_events |

|

user_groups |

|

user_ssh_keys |

|

users |

|

yara |

|

yara_events |

|

yum_sources |

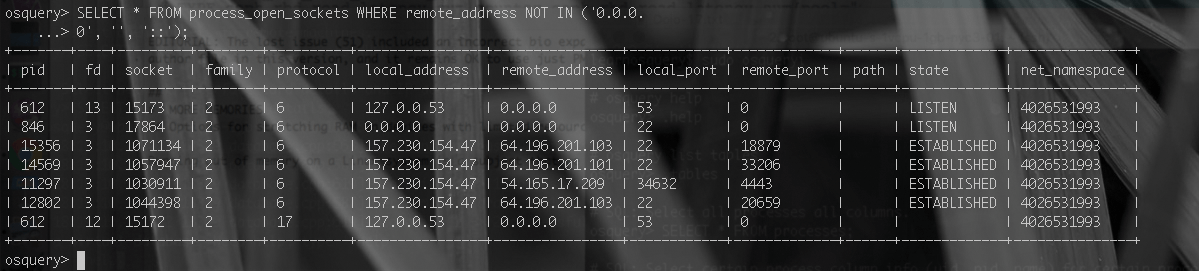

The actual table schema spans a total 229 tables, as detailed by helpful icons in the official documentation [7]. The reason for the difference is that some tables are populated only on a specific operating system (osquery supports Linux, Windows, and Mac OS X). Figure 1 showcases the raw power of osquery with an example of what could be a starting point in the search for a rogue process; a simple query allows us to identify all processes with connections to remote hosts.

Performance Check

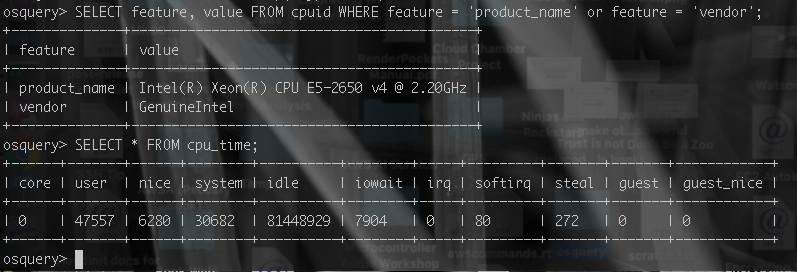

The security applications are self-evident, but what about exploring the performance of a running system? A glimpse of the potential of this tool is offered by Figure 2, where we rapidly identify the exact CPU running the system and proceed to retrieve the processor time slices as defined in the Unix model. Note the inclusion of "stolen" time, indicating a virtualized instance as expanded in a previous article [8].

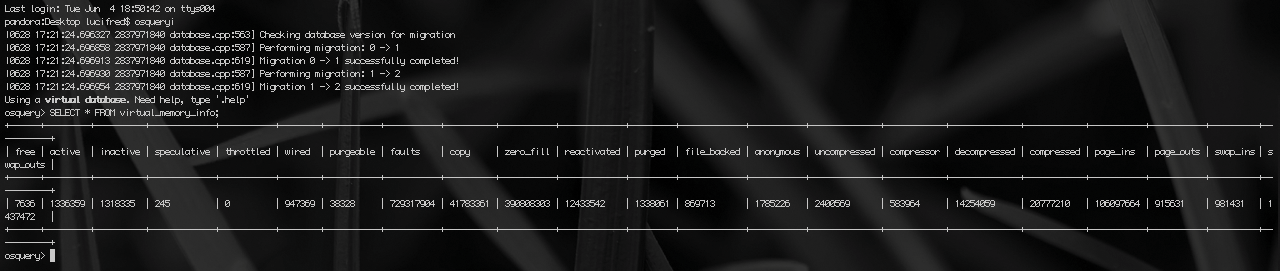

The virtual_memory_info table (Figure 3) exposes up-to-date data on the state of the entire memory subsystem on Mac OS X. Figure 3 also illustrates one of the tool's most irksome minor annoyances: the wraparound of output when tables have too large a number of columns to fit your terminal – this can be easily mitigated by selecting only attributes of interest in a SELECT statement, but it is a recurrent theme nonetheless as one starts exploring new tables.

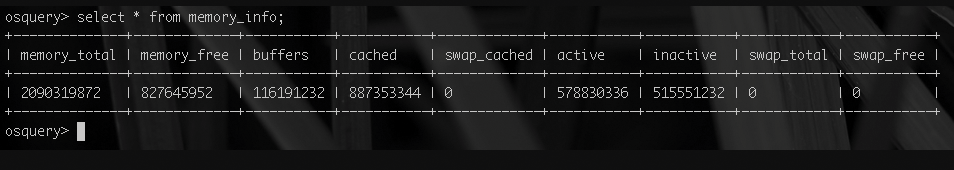

Figure 4 shows the contents of memory_info, which is the equivalent Linux table depicting the current state of RAM. Osquery makes no attempt to create lower-common-denominator abstractions, where information differs significantly across operating systems, and instead dedicates a different table to each design's data when needed in what is a refreshing design choice.

Old Tricks, New Syntax

Classic Unix commands like uptime are immediately available. For example:

shellsession SELECT * FROM uptime;

will produce the traditional day, hour, minutes, and seconds format alongside a total_seconds counter, which may well be more useful to programs. Perhaps the oldest of all performance metrics, the Load Average [9], receives a similar treatment in the load_average table:

shellsession SELECT * FROM load_average;

Note that the capitalization of SQL keywords is stylistically good form for consistency, but it is not required – and your typing speed will benefit from not having to shift case.

The query-based approach to inspecting system state is all the more remarkable when applied to fleets of machines or public cloud instances. Analytics platform vendors like Uptycs [10] provide a way to aggregate and manipulate fleet data from a unified webpage view that complements this tool's powerful database interface visual navigation.

Osquery really shines in its ability to track processes alongside filesystem and user events, leading to its natural effectiveness as a security inspection tool. In time, and with additional performance data exposed in table form, it has the promise not only to become a dependable security-monitoring tool but also to expand into a performance-monitoring instrument for device fleets.