Automatically install and configure systems

Mass Production

Infrastructure automation is ubiquitous now, but long before Puppet, Chef, and Ansible came on the scene, FAI (fully automatic installation) was deploying Linux across servers and installing and configuring software without the need for interaction. Although FAI has been around since 1999, it is still an active project and an excellent option for infrastructure automation.

Auto-Advantages

Automation is the basis for economies of scale as a result of the synergistic effects it generates. The initial work that flows into the automation of a platform then pays dividends with each new node that is added and does not require hours of configuration.

Automation occurs at many levels, starting with the infrastructure and extending to include, for example, switch configuration or the deployment of services and their configuration to turn a basic system into a functioning node that hosts virtual machines in a cloud. Automation also includes the operating system. Rolling out a Linux distribution manually – as every admin knows – is no longer a complicated task, but still a tedious one. However, it's also easy to automate: as Red Hat's Kickstart or preseeding with the Debian installer bear witness.

FAI is a separate software tool that enters the scene with its claim to install Linux operating systems in the shortest possible time. FAI is not limited to a specific distribution; it supports Debian, Ubuntu, CentOS, and other lesser known candidates. (See the "Reinventing the Wheel?" box.)

How FAI Works

In this article, I introduce FAI in a very practical way and explain how the program works and which tweaks you can use. For a better understanding of the big picture, I take a bird's eye view. What strategies does FAI follow? How does it fundamentally complete its task?

More interesting is that FAI offered a similar functionality 20 years ago – with the tools that were available at that time. To be honest, the protocols that are used have not changed so radically since then. Many of them date back to the early days of the Internet.

Old Acquaintances

When a server is powered up or rebooted, you have several options for achieving a running operating system. The first and most common option is to boot from a local storage device – usually the system disk, which contains the regular operating system. Once the server has booted from this disk, the rest of the boot process happens automatically.

However, a server that comes straight out of the box does not typically have an operating system. Although you could install a temporary local boot medium (e.g., a USB stick) manually, that's precisely what you would want to avoid. An alternative approach to installing the system would be booting via a network – not a new invention. Three protocols, all primeval rocks of the Internet, collaborate: DHCP provides a server with an IP address so that it can speak TCP/IP and UDP.

With TFTP, the system downloads a bootloader and boots. From now on, everything that would be possible after booting from a local medium is theoretically feasible. For example, having your own root filesystem on a server in the network and operating the system without a local boot medium – in diskless mode – is no problem.

The combination of DHCP and TFTP, as described in this article, are known as the Preboot Execution Environment (PXE). If a system wants to boot via PXE, at least one built-in network card must support PXE. In the server environment, where servers without PXE-enabled network cards are virtually non-existent, this is not a problem.

With end-user systems, PXE will only be missing if you go for the cheapest available components. Today, you even have comprehensive support for UEFI via PXE, so systems can be booted on a UEFI basis in line with the BIOS successor's requirements.

FAI: Network as Standard

FAI also leverages the ability to boot from the network. The PXE-based boot process is a fixed part of this program, even if it can be bypassed (more on that later). To use FAI, your responsibility is first to appoint a host as the FAI master and run DHCP and TFTP servers on that host. If you already have one or both services on your network, you can reuse them, but make sure the FAI configuration and any existing infrastructure do not trip you up.

For reasons of simplicity, I assume that FAI is used on a single server, where it is responsible for PXE, including DHCP and TFTP itself. The basic system comprises Debian GNU/Linux and the installed fai-quickstart package from the fai directory. I point out explicitly where, if FAI does not exclusively manage the DHCP server, you have to take special precautions.

Ideally, you would want to define at least one deployment network without a VLAN tag, of which all affected network ports are automatically members. Most network cards do not support booting from VLAN-tagged interfaces. Even Intel's chips require special firmware for this, which the manufacturer only releases on request.

After the install, the operating system has to be configured anyway, so any VLAN tags can be configured at the same time. The system installs its operating system in an untagged network and already has the appropriate configuration of the network interfaces at hand when first booting the final operating system.

FAI Configuration

PXE provides DHCP and TFTP for large tasks. The focus is solely on giving the system a bootloader. All other required files need to be sourced elsewhere. If you bear this in mind, the basic design behind FAI becomes apparent very quickly.

The FAI master needs a couple more active services on top of DHCP and TFTP, such as an NFS server with a standard configuration. The NFS server provides various configuration files required by FAI, such as the FAI class configurations, which I will look at later in detail.

NFS is probably not the most popular protocol among admins, and today you might want to use other protocols, but because most of the clients' work is read access, this is ultimately not particularly worrying. Parallel read access to NFS is far less problematic than write access, because locking can be completely ignored.

Once the NFS master has been installed and rolled out, it plays an important role: hosting the FAI configuration files (i.e., the files from which FAI obtains its work instructions). For example, the base files that FAI needs to install an operating system can be found here.

What Happens When?

To visualize the FAI functions, it is useful to visualize the individual work steps. As soon as a server boots into a network boot environment with PXE, it is assigned an IP address by the DHCP server and then, via the next entry, details of the server on which it can use TFTP to search for files.

It is important, depending on the bootloader type used (BIOS or UEFI), that the client search for certain MAC-specific files on the TFTP server. The name of the file contains the MAC address of the network card that makes the request. The PXE standard explicitly provides for this situation, although this statement is not entirely accurate, because the MAC address of the requesting network card plays a second and far more important role in FAI: It ultimately decides whether a server receives an answer to its DHCP question at all.

Admins might also be interested in deploying a server in a PXE environment without immediately rolling out a new operating system with FAI. By default, FAI therefore only takes care of servers that you have expressly added to the DHCP server's database from the command-line interface. In other words, the default DHCP server in FAI lacks the catch-all rule that is usually found in other DHCP configurations. The command

dhcp-edit demohost 01:02:03:AB:CD:EF

demonstrates how a host can be enabled for use in FAI DHCP.

Once the DHCP configuration is done, another important step follows: You need to store a MAC-specific bootloader on the TFTP server so that the client request finds it, instead of falling into a black hole. The command for this is not complicated:

fai-chboot -IFv -u nfs://faiserver/srv/fai/config demohost

The command assumes that it is called on the host with the DHCP configuration, because fai-chboot takes the MAC address from demohost.

Booting a Minimal System

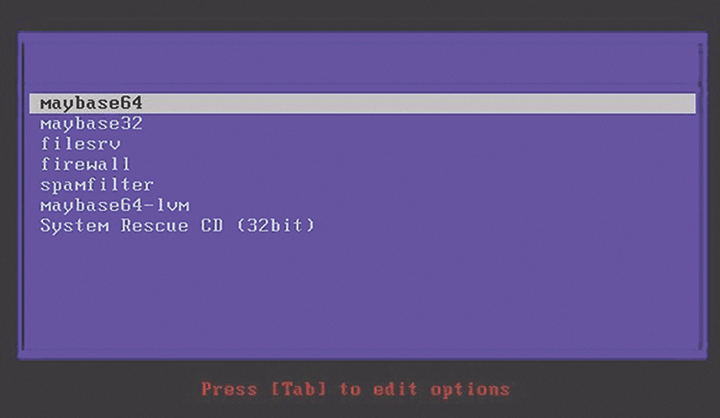

As soon as the appropriate PXE configuration is stored, the client receives the well-known Pxelinux bootloader during the network boot, which in turn loads a classic Debian GNU/Linux-based system, including a RAM drive, with just one task: to support the installation of a local Linux – unless you specify the rescue parameter at boot time. Then, FAI boots into the same minimal Linux but does not automatically start the routine for installing a new system (Figure 2).

Configuration Space

Once the installation routine described above is running, it is very important that you understand the structure of the configuration space on the previously created NFS server. You will discover several folders (classes, disk_config, basefiles, scripts, etc.). All of these directories play a special role within the framework of the FAI process. One of the most important is the classes folder: FAI groups servers by classes and provides a predefined selection of software according to the class.

Remember that at the time a server boots into the Pxelinux bootloader, FAI has no information other than the MAC address with which it sent the DHCP request. This alone is usually too little to allow FAI to decide which operating system the future host should have, which packages should be installed other than the standard installation, and whether – and, if so, which – scripts should run after installation.

FAI helps itself by dividing servers into classes and defining parameters such as the operating system or package selection for the individual classes. The decision as to which class a server belongs is based on several parameters. The hostname can be a parameter, although this is not very flexible. By default, servers already belong to several standard classes (e.g., DEFAULT and LAST). Class assignment becomes genuinely flexible when scripts enter the scene.

During the installation process, external shell scripts can be called via hooks at specific times. You need to store them in the NFS scripts folder so they can be called. The FAI installer then interprets their output as classes to which the respective hosts belong. If a suitable class definition is found in the classes folder, the FAI installer applies the parameters specified in the class definition to the respective system.

Although this sounds quite complicated in theory, it is simple in practice, as a basic example shows: Suppose FAI is being used on a company's workstations and servers. In this case, FAI is executed on a desktop system, but the FAI installer doesn't know this yet, because it only knows the system's MAC.

In the first step of the process, the FAI installer therefore calls a script that reads and inventories the host hardware. It turns out that a powerful graphics card with a 3D chipset is installed in the respective system. Naturally, this is rarely found in servers, so it's probably a desktop.

The inventory script therefore outputs KDEHOST, and FAI knows that the system belongs to the KDEHOST class. The KDEHOST class definition also states that – besides the basic installation – a full-fledge KDE5 and proprietary drivers for the Nvidia graphics card need to be installed. On servers with less powerful graphics cards, the host would automatically end up in the XFCE class, which is also a graphical desktop, but with a less resource-intensive GUI than KDE.

Similar tricks are conceivable even in combination with the latest technology. For example, if FAI notices that a system has dozens of large hard drives, it could output the CEPH class definition. The corresponding CEPH class would then presumably contain details that allow the packages required for Ceph to find their way onto the system automatically, including a basic configuration.

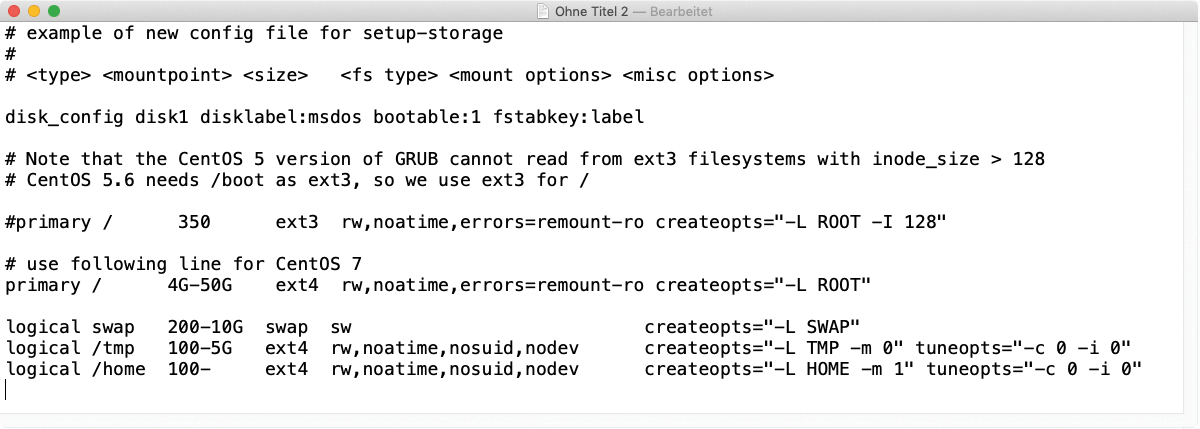

One thing is clear: The class system in FAI is powerful and contributes a great deal to the solution, being so flexible and dynamic. For example, it also ensures that a host is given a suitable hard drive configuration. With the use of files whose syntax is very similar to that of /etc/fstab, you define the layout that the drives should have on the target system (Figure 3).

Even More Scripts

By the way, an extremely helpful interaction arises between classes and scripts. If the output of a class script determines that a host belongs to a certain class, further scripts can be defined that are called for certain operations during the setup. For administrators, this means nothing less than the option of arbitrarily intervening in the setup and its central processes at virtually any time.

The FAI documentation [1] lists the possible hooks and the points in time at which they occur. If you stumble over the term "plan" while reading the documentation, FAI understands this to mean the entirety of all the settings that end up in the installation plan.

Basefiles

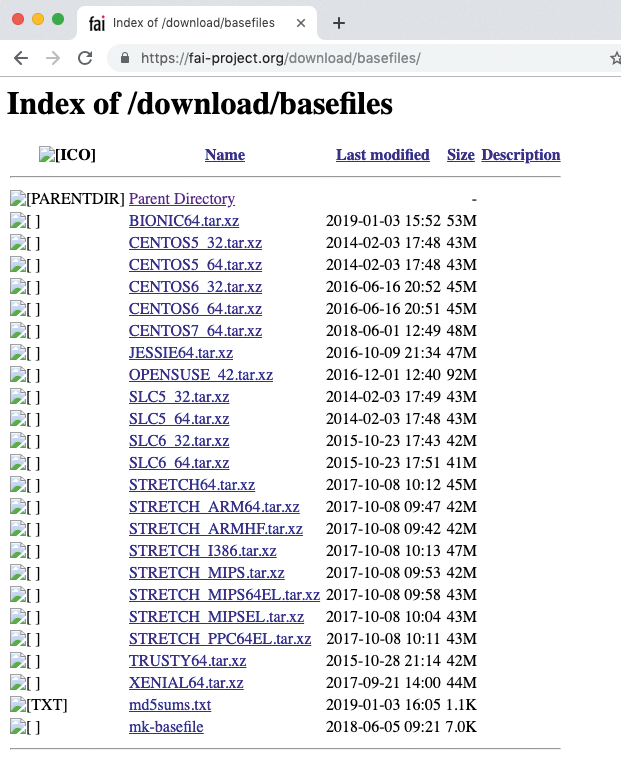

One of FAI's peculiarities is the use of basefiles to install different distributions. I already mentioned that FAI is available not only for Debian and Ubuntu, but for CentOS and potentially any other operating system – as long as it is based on Linux. Therefore, you cannot rely on the installation mechanisms provided by the distributions.

Although, in Debian, installation would be possible with debconf and cdebconf, other distributions simply do not have a separate tool to take care of the system and its base installation. FAI therefore delivers basefiles for various distributions that contain a reduced basic system, which the FAI installer simply copies onto the disk.

Although the FAI developers regularly maintain these basefiles, it can take some time, so if you feel called upon to support the developers in this mammoth task, your desires certainly won't fall on deaf ears (Figure 4).

By the way, the FAI project can't completely hide its preferences, because at least one strictly Debian-specific feature has found its way into FAI. Preseeding of debconf makes possible the automatic configuration of many settings via Debian's system-wide framework for specifying configuration parameters for packages. If you simply store a debconf configuration for a class, when FAI then installs packages on the respective system, it automatically inherits all the debconf entries.

Saving Logs

The FAI developers are well aware of the need to back up logfiles created during system installation. At the end of an installation process initiated by FAI, FAI copies the 10 central logfiles from the minimal Debian system to the FAI server so that they are available to peruse later.

The same function also exists if you use FAI to update your systems centrally. The logs then contain the output produced during this step. The power of FAI with centralized updates should not be underestimated; several tests have shown in the past that a basic update by FAI with its basefiles works just as well as an update by the package manager.

By the way, environments without PXE do not have to forgo the benefits of FAI, because fai-mirror lets you to create an ISO file based on a local setup that can then be saved on a CD or USB stick and used as a local boot medium on the servers. You can thus avoid the whole topic of DHCP, TCP/IP, and UDP, the price being that you can't quickly tweak the configuration on the NFS server.

Conclusions

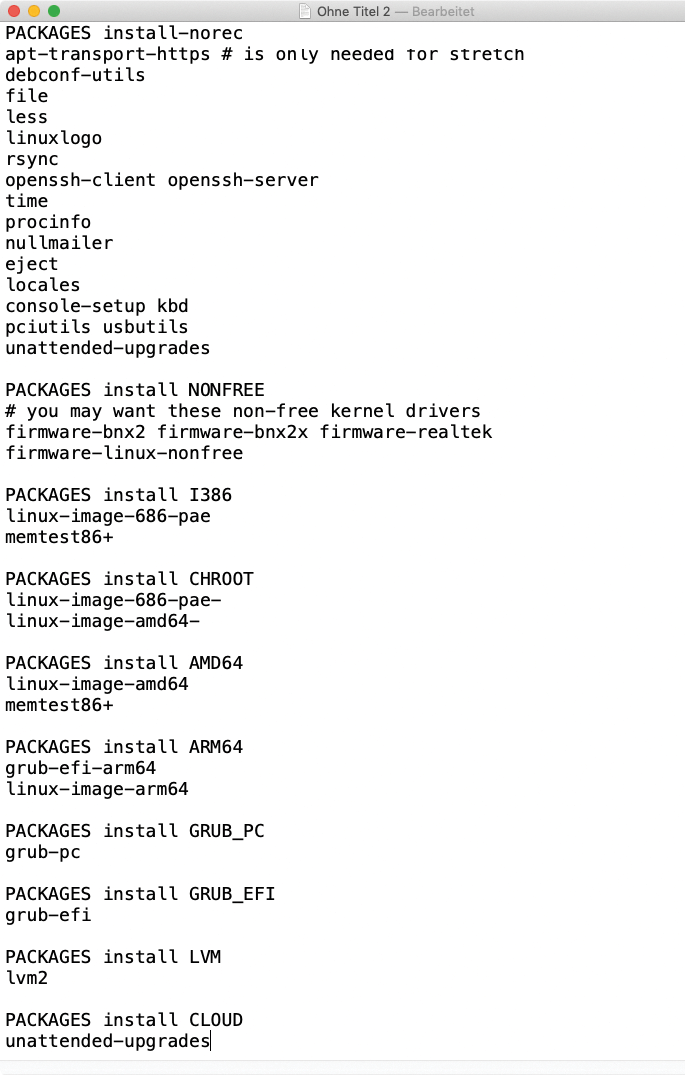

Although FAI is by no means the latest tool, it is at the height of its powers. If you want to roll out many servers quickly and easily, FAI is a reliable choice. Building a working preseed configuration for Debian and running a Kickstart environment for CentOS would be far more complex than the comparable overhead of FAI. The biggest difference between the systems would be the list of additional packages (Figure 5).

FAI may be an oldie, but it is definitely still a goodie.