Keep an eye on your network

Nosy Parker

A Linux installation has many tools to query different aspects of the system. Some tools, like top and ps, give a nice overview, whereas others, like ip, interface directly with the kernel. The number of tools at your disposal quickly multiplies if you manage a network with various operating systems, and, while having access to several utilities sounds like a good thing, juggling them and their respective syntax is quite bothersome.

If you crave a unified interface for querying the different aspects of the operating system, you need osquery. Osquery [1] is a cross-platform open source tool originally created by Facebook that, as its name suggests, is designed to query various details about the state of your machines.

The osquery tool works across Linux, Windows, and macOS and exposes operating system configuration data in the form of relational database tables. In other words, osquery turns a Linux installation into one giant database, with tables that you can query using SQL-like statements. With these queries, you can check on running processes, loaded kernel modules, and active user accounts, and you can even monitor file integrity, check the status and configuration of the firewall, perform security audits of the target server, and lots more. The tool uses a high level of the SQLite dialect, which isn't too difficult to grasp, even for those unfamiliar with SQL.

Loaded Question

Although osquery won't be available in your distribution's official repositories, installing it isn't much of an issue. The tool is available as a source tarball along with pre-packed binaries for RPM- and DEB-based distributions. You can also install it by adding its repository for your respective distribution. In this tutorial, I'll install osquery on top of a CentOS 7 installation.

If this is a pristine CentOS 7 installation, you'll have to update curl and a number of other packages with:

$ sudo yum update curl nss nss-util nss-sysinit nss-tools

Now grab the GPG key for the tool's repository with:

$ curl -L https://pkg.osquery.io/rpm/GPG | sudo tee /etc/pki/rpm-gpg/RPM-GPG-KEY-osquery

Now add and enable the repository with:

$ sudo yum-config-manager --add-repo https://pkg.osquery.io/rpm/osquery-s3-rpm.repo $ sudo yum-config-manager --enable osquery-s3-rpm

Once the repository has been enabled, you can simply grab the tool with yum:

$ sudo yum install osquery

Installing osquery gives you access to three components: osqueryi, which is an interactive osquery shell and is useful as a test bed for performing ad hoc queries; osqueryd, which is a daemon that runs scheduled queries in the background; and osqueryctl, a helper script that will assist you by testing osquery's configuration. You can also use it to start, stop, and restart the daemon. It's important to note that osqueryi doesn't talk to osqueryd in any way, which is to say that osqueryi isn't a client to osqueryd. They are separate but related tools that come together in one package. Most of the flags and options needed to run both are the same, and you can launch osqueryi using the osqueryd configuration file, which is useful for customizing the interactive environment without using lots of command-line switches.

Get Curious

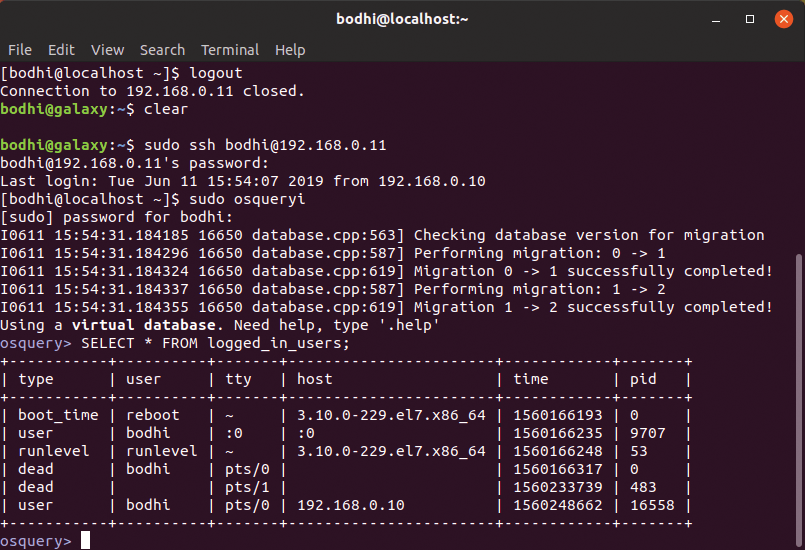

To get started, fire up a terminal and run

sudo osqueryi

to get into the osquery interactive console mode (Figure 1). Before pressing ahead, you should familiarize yourself with some basics. Osquery collects and aggregates a system's log and status information in a number of predefined tables. It is these tables that you query to get information about the state of your system. To get a list of all available tables in osquery, run the command:

osquery> .tables

SELECT statements. Others like UPDATE and DELETE will spit an error.The list of tables isn't really useful, but you can look inside at each table's schema to identify the available columns, column types, and descriptive details. The schema of a table can be viewed with the .schema command:

osquery> .schema users osquery> .schema processes osquery> .schema os_version

Each of these commands will get the schema of the respective table, which will be in the form of CREATE TABLE commands.

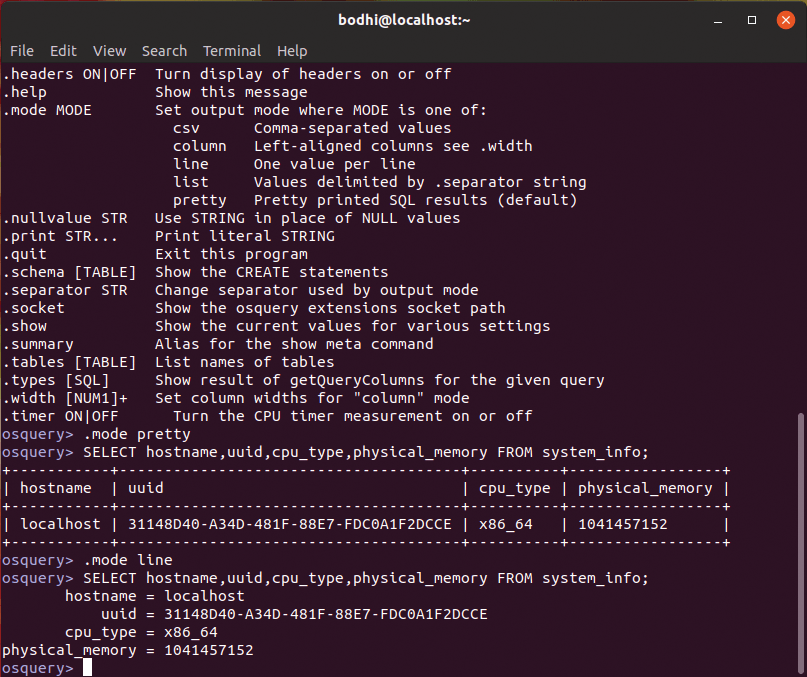

Besides .tables and .schema, various other commands are at your disposal. You can use the .help command to see them all and .show to view the tool's current configuration. One useful option is .mode, with which you can change the display mode for the results (Figure 2).

Riddle Me This

You're good to go now. Note that all the following commands are run in the osqueryi interactive shell. I am omitting the osquery> prompt from now on to save space. For starters, the command

SELECT * FROM processes;

is the equivalent of ps ax and produces a long bit of output that wouldn't make sense. If you replace the * with particular column names, the output becomes more manageable (Figure 3):

SELECT pid, name, path FROM processes;

JOIN and WHERE.For more meaningful output, use

SELECT pid, name, uid, resident_size FROM processes ORDER BY resident_size desc limit 10;

to display the 10 largest processes arranged by size. Similarly, using

SELECT count(pid) as total, name FROM processes group by name ORDER BY total desc limit 10;

will display the process count and name of the top 10 most active processes. Finally,

SELECT name, path, pid FROM processes WHERE on_disk = 0;

displays processes with no associated binary – usually a red flag that means you should immediately terminate the suspicious process.

To keep an eye on the logged in users, use:

SELECT * FROM logged_in_users; SELECT * FROM last;

This query lists previous logins so you can find logins from unknown IP addresses, especially if multiple users are logging in from an unfamiliar host.

Also, you can check the repositories available in your distribution. On CentOS, this information is retrieved from the yum_sources table with:

SELECT name, baseurl, enabled FROM yum_sources;

Use the WHERE operative to restrict the view to only the enabled repositories:

SELECT name, baseurl FROM yum_sources WHERE enabled=1;

You can bring up an alphabetized list of all installed packages with:

SELECT name, version FROM rpm_packages ORDER BY name;

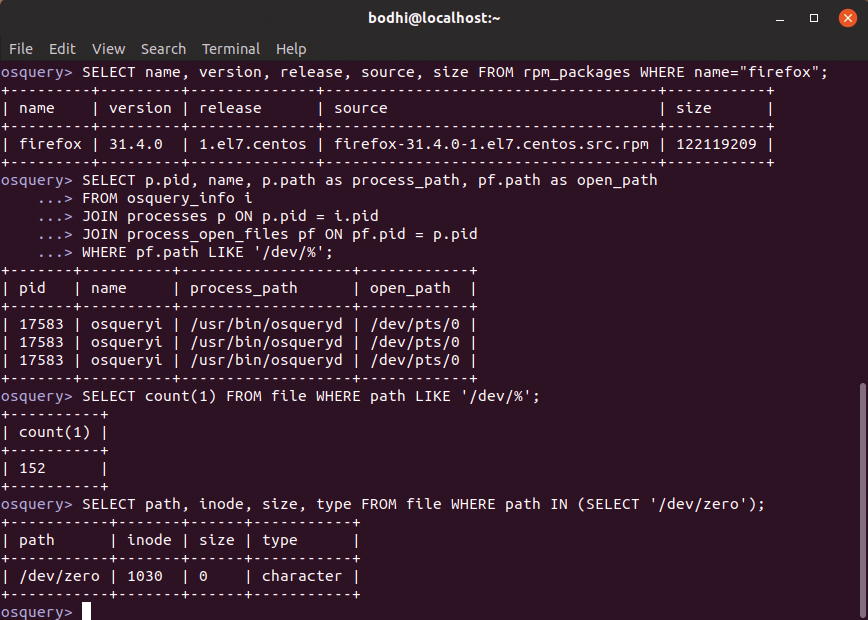

To look for a specific package, you can append the name filter:

SELECT name, version, release, source, size FROM rpm_packages WHERE name="firefox";

You can also use osquery to keep an eye on network traffic. The

SELECT * FROM listening_ports; SELECT * FROM suid_bin;

commands list all the listening ports and find the files that are setuid-enabled, to help you find backdoors on the server and detect backdoor binaries. Often attackers delete the malicious binary file after running it in the system. You can find such processes with:

SELECT name, path, pid FROM processes WHERE on_disk = 0;

The queries

SELECT * FROM kernel_info; SELECT name, size, used_by, status FROM kernel_modules where status="Live" order by size;

help identify outdated kernels and list all loaded kernel modules. You'll also want to run these queries periodically and compare their output against older results for any changes.

These are just a handful of enquiries you can make with osquery. Read through its documentation, especially the schema for the tables [2], to gain its true potential.

Speak of the Devil

The other important component of the utility is the osquery daemon, or osqueryd. It sits in the background and executes scheduled queries. Although osqueryd is installed along with osqueryi, it's not enabled by default. For that, it requires a configuration file.

Creating a configuration file also makes it easier to run osqueryi. Instead of having to pass a lot of command-line options, osqueryi can read those options from a configuration file. The tool looks for the configuration file at /etc/osquery/osquery.conf, but it does not ship with one. Instead, you can copy the sample configuration file that's available in /usr/share/osquery/osquery.example.conf.

The configuration file uses the JSON format. The sample file is commented out by default, and you can uncomment the options you want to enable. You can find the complete list of options and settings in the osquery wiki [3].

The configuration file is divided into three sections, as shown in Listing 1. At the top is the list of daemon options and settings read by both osqueryi and osqueryd, followed by a list of scheduled queries and when they should run. At the bottom is a list of query packs that contains more specific queries.

Listing 1: /etc/osquery/osquery.conf

01 {

02 "options": {

03 "host_identifier": "hostname",

04 "config_plugin": "filesystem",

05 "logger_plugin": "filesystem",

06 "logger_path": "/var/log/osquery",

07 "disable_logging": "false",

08 "schedule_splay_percent": 10

09 },

10 "schedule": {

11 "osquery_profile": {

12 "query": "SELECT * FROM osquery_info;",

13 "interval": 60

14 }

15 },

16 "packs": {

17 "ossec-rootkit": "/usr/share/osquery/packs/ossec-rootkit.conf",

18 "it_compliance": "/usr/share/osquery/packs/it-compliance.conf",

19 "incident_response": "/usr/share/osquery/packs/incident-response.conf"

20 }

21 }

I've used several options in the configuration file. The host_identifier field is used to identify the host running osquery in the logs. Using hostname simply inserts the hostname of the computer on which the daemon is running. The config_plugin=filesystem option asks the daemon to retrieve the configuration file from the disk.

Similarly, logger_plugin=filesystem asks it to write the logs to the filesystem. Related to it is the disable_logging=false option, which asks the daemon to log its activity, and the logger_path option, which specifies the location of the log. Lastly, the schedule_splay_percent option ensures that queries inadvertently scheduled to run after the same intervals don't clash with each other by adjusting their schedules by 10 percent.

Booster Packs

Besides the options, I've also added a query to the configuration. Although I've added just one query to my configuration file (line 12), I have also included three query packs (lines 17-19). Query packs [4] are JSON files that contain additional queries. Think of them as software libraries that you've just imported into the configuration file.

If you want to view or change the queries that will be running from the packs, you'll find them under the /var/osquery/packs directory. It's a good idea to scan the queries inside packs that you want to use because you might want to change the interval at which a query runs or perhaps even disable some that aren't applicable to your machines.

When you're done, save and close the file and validate it with the command

sudo osqueryctl config-check

Make sure there aren't any errors and double-check to make sure all open fences are closed at the right spot. If you close them early, osqueryctl will not give any errors, but the config file won't function properly.

If you want to see all of the queries that are scheduled to run from the config, use:

SELECT name FROM osquery_schedule;

This command will display all scheduled queries, including those from the packs.

Now that you have a valid configuration, you can start osqueryd with either the systemctl or osqueryctl helper script, such as:

$ sudo osqueryctl start

As soon as the daemon comes to life, it will create the /var/log/osquery/osqueryd.results.log file to store the generated results. The results will start showing up as soon as the scheduled queries and packs are run. Unfortunately, osquery does not have an alerting facility, so you can't see the results of scheduled queries unless you view the results file. You can, however, use the tail command to stream the last 10 lines of the file continuously to your screen:

$ sudo tail -f /var/log/osquery/osqueryd.results.log

Now you can forward the results logs to any external application (e.g., Zentral [5] or Elasticsearch [6]) for log analysis and alert generation.

As you can see, osquery is a powerful tool that's useful for investigating a single or multiple systems using the simple SQL syntax. You can use it to make one-off queries or combine it with a log analysis app for a comprehensive threat-monitoring system.