Red Hat Enterprise Linux 8 pre-series test

Stable Future

For more than 15 years I have been a Debian developer, so I am used to a good deal of teasing about "Debian Stale," a corruption of the name of the Debian Stable branch. However, if you look at common intervals between enterprise distributions, you will notice that Debian is one of the more agile distributions. Only Canonical sticks slavishly to a plan to release a version with long-term support every two years; elsewhere, five years is the norm.

Now, after more than four years, Red Hat is launching a new version of its flagship – Red Hat Enterprise Linux 8 (RHEL 8) – which is intended to ditch a large amount of ballast. "Every Enterprise, Every Cloud, and Every Workload" is the motto – reason enough to become acquainted with the new product in the pre-series test.

Pre-series testing means that, at the time of writing this article, only the public beta version of RHEL 8 [1] was available, which naturally still has some bugs. This text is primarily about the new features that RHEL 8 offers – paying customers can assume that the final version will meet the usual Red Hat stability standards.

Target Groups

When Red Hat promises "profound" change, it is worth taking a closer look at that promise. In the past four years much has happened in terms of technology, and many new solutions have developed (e.g., Kubernetes). In RHEL 7, Docker and its support for Red Hat's container platform was not yet available because Docker itself was just a technology preview. Nevertheless, it's safe to say that many companies have run Docker on RHEL 7, presumably with Docker's own packages. Now, however, the solution has the official Red Hat blessing, with the new RHEL version taking a giant leap forward.

From the start, RHEL 8 was unlikely to change everything. Red Hat is faced with the thankless task of reconciling two completely different worlds. The first group comprises the traditional clientele, who see RHEL primarily as a tool for reliably equipping a server with an operating system. The new functions hardly play a role in this case, because stability is the highest goal. Admins of such systems respond very nervously if updates impair existing functions. This group prefers the old Debian update mantra: New packages are only needed to mend security holes or put critical functional problems to rights.

The other group of customers is fully committed to automation, the cloud, and containers and virtualization. Because of the "immutable underlay" principle, keeping every host of the platform in perfect condition at all times is not absolutely necessary. If one system fails, another takes over the tasks; later, the admin restores the system with an automated process. New features in management software (OpenShift, OpenStack, or Kubernetes) are given preference over unconditional stability.

Red Hat wants to address both target groups with RHEL 8 in some way (but not always directly) by pursuing an alternative strategy for Kubernetes, OpenStack, OpenShift, Ceph, and other products. RHEL has the task of providing a basic system that is then supplemented by packages from additional directories. Conversely, this also means that if RHEL 8 does not turn out to be the stable system everyone expects, sooner or later the add-ons based on the new version will also have problems.

Red Hat has much at stake. In fact, the first release of RHEL 8 has to be perfect for both scenarios described above.

Fedora Basis

Critics claim that Red Hat has offloaded the work on the main distribution into the community through the introduction of Fedora, subsequently cherry picking features for its own enterprise distribution, but that's not true. Although Red Hat Enterprise Linux 8 is based on Fedora, it is by no means the case that Red Hat does not contribute anything to Fedora.

Quite the opposite: Most of the work that takes place on Fedora is still done by Red Hat people. Although they are happy about occasional community deliveries, the majority of the work is definitely not done by the community. Meanwhile, Fedora fans are pleased that the byproduct of the work on Red Hat's enterprise system is a desktop distribution that gets updates on a far more regular basis than does the enterprise version.

RHEL 8 inherits all the relevant system parameters from Fedora 28. The basis of the system is a reasonably up-to-date 4.18 kernel, which already officially has long-term support from Linux developers. At the time of the RHEL 8 release, however, it will already be a couple of months old; Linux 5.0 will have been available for a long time by then.

The problem is that RHEL 8 will not see a major update of a new kernel throughout its lifetime. Whereas Ubuntu offers the LTS kernel and provides its current LTS version with newer kernels, Red Hat takes a different approach and ports many bugfixes and drivers to the old kernel.

After some time, this means you have a genuine old-timer spiced up by a colorful mixture of ports. Admins are unlikely to care. If you buy the Red Hat Enterprise version, you will get support and can simply open a ticket if the kernel doesn't do what it should.

The 4.18 kernel in RHEL 8 can be run on four architectures: AMD64 (i.e., x86-64), 64-bit ARM, and the little-endian versions for IBM Power and IBM Z. For the majority of users, however, only AMD64 and perhaps ARM 64 are likely to play a role. The two ports for IBM architectures see Red Hat serving a fairly small and highly specialized customer segment.

Desktop

What many people tend to forget about enterprise distributions is that the systems are intended for both desktops and servers. However, Linux on the desktop is an issue in its own right; most users prefer the typical desktop distributions like Fedora or openSUSE to the enterprise versions.

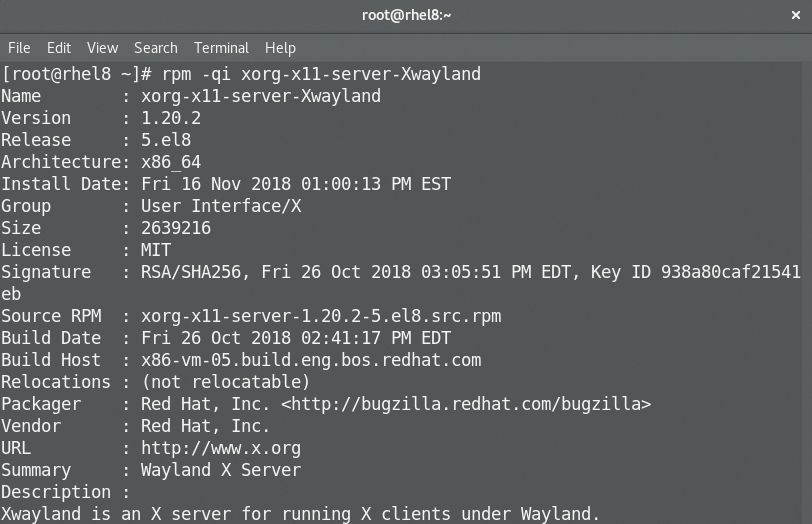

Nevertheless, RHEL 8 also delivers graphics: Part of the package is the Wayland replacement for Xorg with Gnome 3.28, which is also the default desktop. The bond between Red Hat and Gnome is traditionally close, so this decision is not surprising. The classic Xorg X server is also available for those users who prefer this variant to the new Wayland option (Figure 1).

Packages

Version maintenance is on the agenda right now, so RHEL 8 inherits most of the packages of the Fedora 28 desktop version, including Python 3.6, MariaDB 10.3, PostgreSQL 9.6 and 10, up-to-date Apache and Nginx, and current versions of various tools. If you are not looking for a feature that was only introduced into a tool after Fedora 28, you won't have any problems.

In RHEL 7, the manufacturer has treated the programs in its system like its kernel: Updates are only available in homeopathic doses and certainly not for new program versions or new features. In RHEL 8, the intent is to change this relationship fundamentally. The manufacturer has even rebuilt its package manager, which in itself is a rare event. The current version of the Red Hat Package Manager (RPM) is capable of handling AppStream [2] metadata (see the "AppStream" box).

Repositories

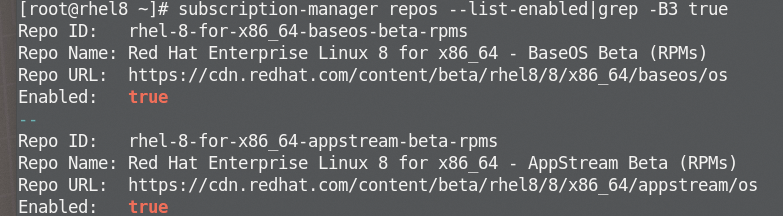

In RHEL 8, the introduction of AppStream ensures that only two repositories need to be enabled on the system for the various package tools: The BaseOS repository, which, as before, contains all core components of the operating system and is subject to the same strict rules that RHEL has been subject to thus far, and the AppStream repository, which contains the majority of applications that mostly run in userspace (Figure 2). Because the appstream directory can also contain different versions of a package, the admin can choose which tool to use during installation.

The lifecycle of an AppStream application is completely decoupled from that of BaseOS. The basic system thus functions as before and nothing stands in the way of importing new applications via the AppStream mechanism. Because AppStream only makes a statement about the metadata of the software and not about the form in which the data has to be available, containers are very much conceivable in this setup.

The AppStream format is getting ready to become a kind of cross-distribution package manager for containerized applications, which could lead to less diversity but would have the technical advantage that Docker containers can be deployed in a reasonably universal way.

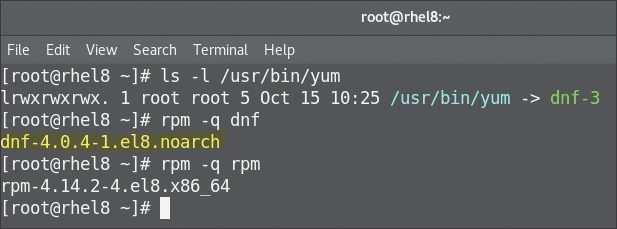

New Yum

Much has also happened with Yum, which is now based on DNF in RHEL 8, a completely new framework that Red Hat built specifically around RPM (Figure 3). Although this change did not really affect the test, according to the manufacturer, Yum is now more robust and, above all, faster than in the previous version. The performance of a tool like Yum also depends on the hardware available on site.

yum command can still be called, but it is only a link to DNF.One advantage of DNF over Yum is that it offers a defined and standardized API interface other components can use to access its functionality. Yum had only one approach: on the command line with the yum command, which of course implies all the disadvantages that shell calls to scripts and programs entail.

Network News

If you are running a RHEL-based firewall, you have to be prepared for several changes, the biggest of which relates to the packet filter. Officially, RHEL 8 nftables is the successor to iptables, which Red Hat is retiring. If you want to take it back out of retirement, you will still find the tools and kernel modules on the system, but you are well advised to reconsider this step: Red Hat is not replacing the outdated iptables without a good reason.

Nftables solves the problem that iptables, after 20 years in the kernel, has reached the end of its life. In 1998, iptables replaced the unpopular ipchains, which had replaced ipfirewall, or ipfw, not so long before.

Iptables was fine for the requirements of the time, but the iptables architecture in the kernel is unsuitable for today's requirements given network cards capable of 200Gbps and more. The kernel developers have long since used all sorts of hacks to squeeze the last bit of performance out of iptables. In cloud setups, iptables is often the component that limits throughput.

Nftables is the kernel developers' way to solve the problem. One of the solution's biggest advantages is that admins no longer have to deal with different userspace programs (iptables, ip6tables, ebtables, and many more). Nftables offers all functionality under a uniform interface.

Integration in firewalld is also provided; in other words, if you have been configuring your firewalls with firewalld, you will not need to learn new tricks. All that remains is the exciting question of whether nftables – whose incompatibility with iptables has long been considered the biggest vulnerability – will remain the state of the art for a while or whether it will be replaced in the near future by the Berkeley Packet Filter (BPF), which I discussed in detail in the previous issue [3].

The infamous network scripts found in /etc/sysconfig/networking in RHEL 7 are no longer there in RHEL 8. Now, only the network manager takes care of the interface configurations.

In RHEL 8, the Cockpit software is part of the standard scope. Cockpit, an alternative to Webmin, is an administration GUI developed in large part by Red Hat that enables access to the most important parts of the system configuration from your browser. The component can be disabled if desired; you have no obligation to use it (Figures 4 and 5).

Supercharged KVM and Docker

The Qemu KVM version 2.12 included with RHEL 8 provides support for various extensions that are often used in high-performance computing. The Q35 PC machine type, which effectively uses the PCIe features of Intel I/O Controller Hub 9 (ICH9) chipsets and newer, is included, as is better support for Nvidia GPUs.

Ceph can now be used as storage for KVM virtual machines (VMs) on all CPU architectures supported by RHEL 8. Virtual CPUs (vCPUs) can now be activated and removed without stopping the VM, and if you want to use UEFI within a VM, Qemu KVM now has a corresponding UEFI BIOS that makes this possible.

Red Hat does not want to deal with the topic of containers only in the context of OpenShift and the like but leaves no doubt that containers should be an integral part of RHEL 8. The way it is technically implemented, however, is likely to cause some frowns, especially among Docker aficionados.

Clearly, Docker's merits for containers under Linux are undisputed – to some extent, the company has taken the issue from the realm of the dead back to this world. However, it has also led to "containers under Linux" and "Docker" sometimes being used synonymously – and that's a thorn in Red Hat's side. On the one hand, all container implementations for Linux use the same kernel features (e.g., namespaces and groups), and, of course, Red Hat is involved in their development.

On the other hand, Red Hat cannot be interested in Docker dominating the Linux container market; therefore, Red Hat quickly developed its own container format and placed it under an open license, the Open Container Initiative (OCI).

In RHEL 8, Red Hat is now strongly pushing this format into the market and delivering the tools to do so, which – in the style of Docker – let you manage containers, build container registries, and even build containers yourself with three tools: Buildah, Skopeo, and Podman.

Container Tools

Buildah creates, as its name suggests, the functionality of Dockerfiles, which comprise the steps needed to build a container. Buildah imitates this functionality, but for containers in OCI format.

Skopeo is something like a container reload point: The tool helps to find container images and can tap into a variety of sources. In addition to Docker registries, other OCI registries and even local directories with images are supported.

Finally, Podman is a command-line tool that lets you control containers on your local system without the need for a control daemon, as is the case with Docker. This arrangement removes a vulnerable component from the equation and reduces administrative overhead.

If you look at the architecture of the container implementation in RHEL 8, you'll quickly realize that you have no need to concern yourself with Docker anymore. Docker itself said in a blog entry [4] as early as 2017 that it took a relaxed view of OCI – being one of its biggest contributors – and pointed out that OCI is only a container format, whereas Docker provides a complete collection of tools for creating and managing containers.

Exactly this objection has now been convincingly refuted by Red Hat in RHEL 8, and this move can be interpreted as an all-out attack on Docker. Additionally, RHEL 8 is likely to be the successor to most customers currently using RHEL 7, so the components described here will be found sooner or later to be integral parts on a huge number of systems. Docker's reaction to this critical circumstance might therefore be quite interesting to observe in the future.

Stratis Storage Manager

One important innovation in RHEL 8 must not go unmentioned: The system now has on board out of the box Stratis, a storage manager for volumes and encrypted volumes. Stratis can manage existing filesystems but can also create new filesystems; it can also combine various components of the block device layer in the Linux kernel (e.g., LVM) to achieve effects such as encryption or improved caching. Pooling of devices is also possible via LVM.

Stratis uses XFS as the default filesystem, which is remarkable: Btrfs should have reached a state in which it could be the default filesystem for RHEL 8, as should ZFS, although its license conditions make its use in RHEL 8 impossible. Red Hat works around these problems by combining the extremely robust XFS with various other technologies, and it worked quite well in the test.

Installation

The RHEL 8 installer hardly differs from the previous version. If you want to set up a single RHEL system, you can achieve your objective quickly and easily. However, because RHEL 8 also seeks to be the perfect platform for cloud computing, Kickstart and Anaconda are available, as well, which together enable automatic RHEL installation.

If you use Red Hat's OpenStack platform, for example, you can roll out RHEL 8 directly to the target systems from the tools there, without even seeing the installer. Basically, only the version number changes; the highly functional features all remain the same.

Conclusions

Red Hat RHEL 8 has mastered the balancing act between a rock-solid system on the one hand and a flexible distribution that picks up on current trends on the other hand. The AppStream repository, where Red Hat offers a variety of programs (including current versions in the future), and AppStream support are very useful. The genuine innovation in this new version is that the RHEL installation no longer forces you to run a software museum.

Container support is also fun: The consistent use of open standards (OCI) and the management framework that Red Hat provides for containers are a sensible alternative to Docker and, thus, take a bit of the wind out of the Linux container king's sails.

Additionally, the distribution is down-to-earth: Updates such as the switch to nftables have positive effects in everyday life, even if they seem fairly unspectacular. All told, RHEL 8 can be considered a success and a stable foundation for Red Hat products in the years to come.