Plundering treasures with Gitrob

Get Secure

Hidden in the not-so-dark depths of many software repositories lurks a server estate's potential downfall. Before more refined processes are learned and adopted, newcomers to the art of using DevOps tools find themselves facing the easier route of storing secret keys and passwords in software repos for convenience.

Even for supposedly mature estates, with many sets of eyes working on security and feature development, it's not uncommon to find legacy access keys buried deep within code that are still valid and represent a security risk to an organization.

In this article, I look at a powerful tool built specifically to automate the search for precious credentials, Gitrob [1], which sifts through potentially hundreds of thousands of lines of code to find passwords, secret keys, tokens, and anything vaguely resembling authentication credentials.

The Gitrob README file talks about being able to "help find potentially sensitive files pushed to public repositories on GitHub." Of course, it's also bad practice to store credentials in private repos, because with an accidental flick of a switch, it's all too easy to make a repo public. I'll explore how to use Gitrob with minimal permissions on public repos to sort the wheat from the chaff within GitHub. Because Gitrob is open source software, you can fork it and tweak it further for your own needs.

Other Tools

A few other popular tools behave slightly differently from Gitrob. For example, git-secrets [2] is an Amazon Web Services (AWS)-specific tool you can find on GitHub. You can usually integrate these types of tools into your continuous integration/continuous development (CI/CD) pipeline tests with relative ease. The AWS tool describes its purpose neatly and succinctly as preventing "you from committing passwords and other sensitive information to a Git repository," and it runs with a variety of options for your own edification.

Macramé

Before looking at Gitrob in more detail, I'll take a moment to talk about what these tools are doing, which is really just scanning for predefined strings within shed-loads of text, or indeed files or file paths.

To begin, I'll try a manual experiment on GitHub. Be warned: It can take a pinch of patience and a smidgen of detective work to reap any useful results. First, you should log in to GitHub.

Although you have a lot of different strings for which you could search, having mentioned AWS, I'll make a few tries at hunting for AWS credentials. Sometimes you need to hunt inside a specific GitHub organization [3], so note that I'm including the name of the organization in some of these search URLs.

Make sure you're a member of the organization first, or GitHub might deny that a page is present that you know definitely exists. Alter the URLs that follow for both your private repos and organizations to suit your own needs. In this case, an organization's repos can be scanned by interpolating your organization name somewhere inside the URL.

The first example URL looks at keys. If you're using the AWS service that deals with Key Management Service (KMS), then a good string for finding files in your organization's repos with references to KMS is:

https://github.com/search?l=&q=org%3A<organization>+kmskey&type=Code

Next, I'll look at something a little more universally helpful: AWS access keys. If you've used AWS and its command-line interface (CLI) for a while, you'll be more than familiar with declaring your credentials (Listing 1) so that AWS Identity Access Management (IAM) will let you log in over the CLI.

Listing 1: An Obfuscated ~/.aws/credentials File

[default] aws_access_key_id = XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX aws_secret_access_key =XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX region = eu-west-1

As you can see, the two strings you'll clearly want to search for are "aws_access_key_id" and "aws_secret_access_key." Note that these two strings are used in upper- and lowercase, so keep that in mind. I'm not sure whether the GitHub search engine is case sensitive, but with some digging, you can determine whether it is or not.

The resulting URL for the "secret" key, for example, would be:

https://github.com/search?q=aws_secret_access_key&type=Code

Note that if I run this search over all of GitHub (and not just my repos), it uncovers a whopping 572,000 or so results. Many entries are innocuous, of course, but nonetheless, be warned that attackers get up pretty early to catch out victims.

The second-to-last manual example looks at public repos (without naming the organization) for SSH key pairs used by Elastic Cloud Compute (EC2) servers:

https://github.com/search?l=&q=key-pair&type=Code

In the same vein, finally consider what a standard private SSH key looks like with the header (Listing 2).

Listing 2: Abbreviated Private Key Header

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY----- MIIJKQIBAAKCAgEAwm7kMWjLOTXkXVmpBT+q2YxfXyoyqpzh4vPeGWbBa53VzR MNuIqPpV9HHmkDsCo0yGijVm0lH3qoHHcUtMH4cpYuBSjKnIT78VK/TGvZCgL37K iYm71yE5BaFQSt+A5Wrlr8TDeNjHOOKY/3pInx79zr37w9OyT84dUwBfmn9Au0H8 HjA+1veU0FJLmj/LxvfA+tWM2l93HODwVar6NWqu9OQMw+XgX86UDo30b0MJb4iL aENiukjDEW08bhjEJ3AbELoJgnT2jNmilDEwO8whW6jCaeHTqDkx5dElst/G0cSF

The URL to look for private keys might be:

https://github.com/search?q=BEGIN+RSA+PRIVATE+KEY&type=Code

Worryingly, the search using that URL found 2.5m entries with a private SSH key mentioned, any of which could potentially lead you to a functioning SSH key! Again, many code snippets are referencing dummy keys and the like, but that's lots of room to find mistakes coders have made.

Of course, you could also search for registry credentials to access container image registries, for example, but I'll leave you to hunt more yourself. I hope these examples have whet your appetite sufficiently for the type of stuff you need to bear in mind. Now, on to some welcome automation to reduce the workload.

Persona Non Grata

With the sophisticated Gitrob tool, you can automate in-depth scans of your repos to expunge unwanted entities. Gitrob is written by security professional Michael Henriksen [4]. Formerly written in Ruby, Henriksen, has given Gitrob a complete rewrite in Google's Go programming language and somewhat simplified the tool to help prevent code bloat and tiresome development. Gitrob focuses on a few facets of familiar signatures. If you want to create your own version and build a binary from source, you can find the code, which lists the signatures, on GitHub [5].

Before I go any further, and having given you food for thought on what to search for, have a look at the signatures code to familiarize yourself with Gitrob's approach. You'll note more of an emphasis on path, file name, and file extension than my manual searches did above – with a bunch of regular expression matching thrown in for good measure.

By using Go, rather than Ruby, the route to installation is vastly reduced because precompiled binaries are available, significantly lessening dependency pain. These ready-made binaries also include a slick GUI that pops up on your local machine after a scan, which means, if you're looking at lots of Findings, it's much easier to analyze their severity and repo location.

Env != Sane

Gitrob needs at least Go v1.8; my Linux Mint laptop (based on Ubuntu 18.04) carries version 1.6 in its package manager. To remedy this, I installed version 1.8 manually [6], which required the commands in Listing 3, executed as superuser. The tarball is about 85MB compressed.

Listing 3: Go v1.8 Install

$ curl -O https://storage.googleapis.com/golang/go1.8.linux-amd64.tar.gz # Or your platform's tarball $ tar -xvf go1.8.linux-amd64.tar.gz # Or your platform's tarball filename $ mv go /usr/local $ export PATH=$PATH:/usr/local/go/bin # Add a line to your .bash_profile or .bashrc to add Go permanently to your PATH $ go version # This should say "go1.8"

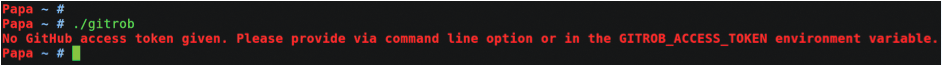

Now that Go is working, your next task is to install Gitrob. You can choose the relevant file for your platform from the GitHub releases page [7]. I went with gitrob_linux_amd64_2.0.0-beta.zip, which is a little more than 6MB in size and 21MB uncompressed. After downloading the file (e.g., with wget), I checked that the binary suited my system by running the ./gitrob binary without any options (Figure 1).

You can also build a binary from source with:

$ go get github.com/michenriksen/gitrob

According to the Gitrob README, this command will "download Gitrob, install its dependencies, compile it and move the Gitrob executable to $GOPATH/bin."

On Your Bike, Fella

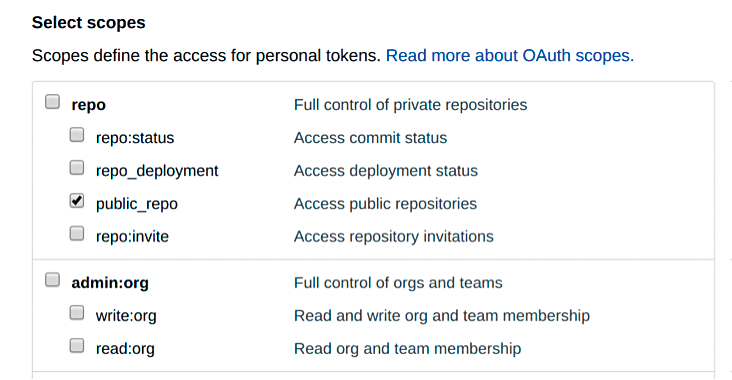

As you can see by the response in Figure 1, the last thing you need to do is give Gitrob the credentials to sift through your repos [8]. The note at the top of that page explains that you need tokens when you're using two-factor authentication and to access protected content in an organization that uses SAML single sign-on (SSO). In summary, creating a token requires logging in to GitHub and clicking Settings | Developer Settings | Personal Access Tokens | Generate new token. Figure 2 shows the minimum access I allowed in my case, which is to access only public repos.

Next, take a copy of the token and keep it somewhere safe. You'll only see it displayed once, like an AWS secret key, for example. However, pay close attention to the warning on the GitHub help page: "Warning: Treat your tokens like passwords and keep them secret. When working with the API, use tokens as environment variables instead of hardcoding them into your programs."

If you aren't using the token for Gitrob, you would simply use it like a password on the command line (noting the multifactor authentication comment above). The example on the GitHub instructions page is:

$ git clone https://github.com/username/repo.git Username: <your_username> Password: <your_token>

Finally, also note that only HTTPS software repos suit tokens. If SSH is in use, then follow the instructions from GitHub on how to change a remote URL from SSH to HTTPS [9].

Expelliarmus

Now it's time to get to the juicy stuff and target some accessible repositories. Use your token with Gitrob and, as GitHub advised, run the environment variable command (insert your own token, of course):

$ export GITROB_ACCESS_TOKEN=8XXXXe15a9decXXXXXXXXXX358bf3XXX

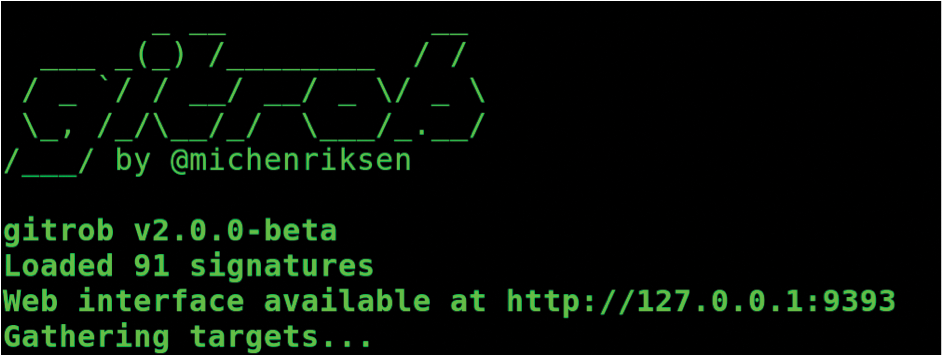

Now, if you run ./gitrob again on the command line without options, you should see a very welcome piece of ASCII art (Figure 3).

Besmirched

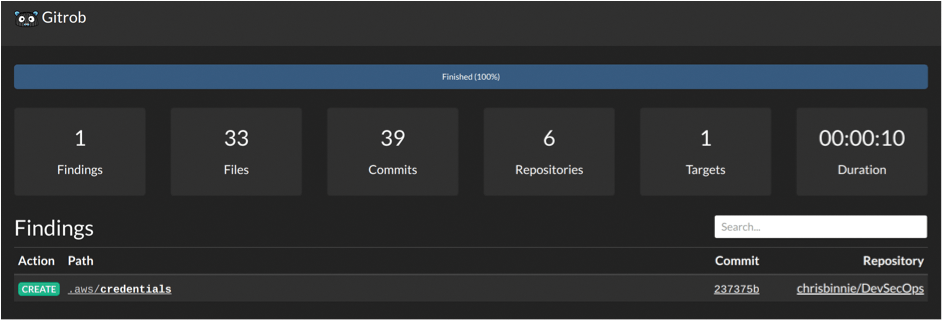

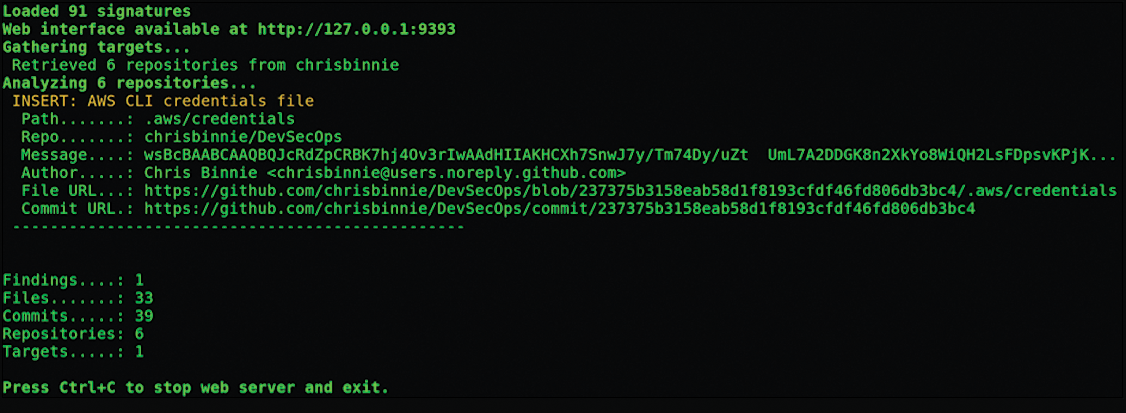

As you can see in Figure 3, Gitrob points you to a web interface (running on the local machine on TCP port 9393), which you'll use later. The next command asks Gitrob to traverse the public repos (there should be six). The results with clickable links (Figure 4), which you can see by directing your browser to http://localhost:9393, report any Findings that needs further investigation.

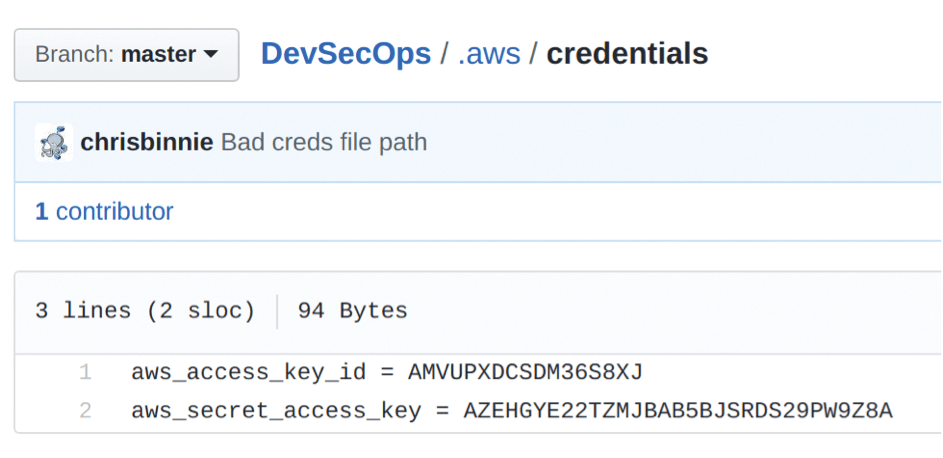

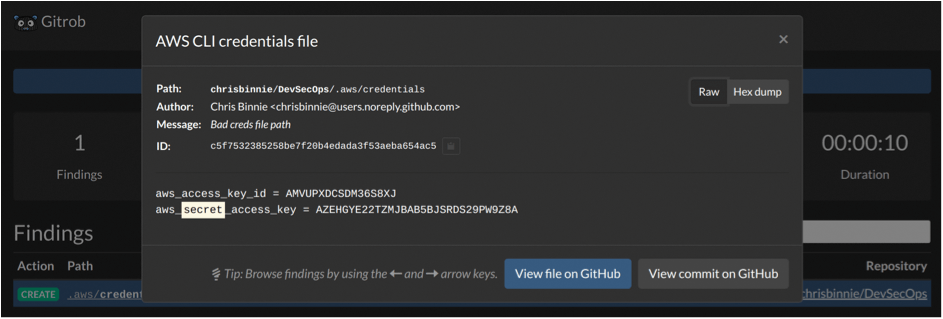

Clicking on the offending .aws/credentials link at the bottom of the GUI displays the AWS credentials file (Figure 5), which looks valid, but isn't. (In this case, it's a dummy test file designed to trigger a result from Gitrob.) The pattern that was flagged as suspicious must have been present in the aforementioned signatures file [5]. Following the Findings link in the Gitrob GUI shows more detail (Figure 6), and even a link to the file.

The Gitrob CLI also gives good feedback (for CI/CD pipeline integration, among other things). Figure 7 shows Gitrob displaying the nasty finding in detail.

The End Is Nigh

As I'm sure you will appreciate, Gitrob provides extremely valuable functionality. Human mistakes, such as typos and a lack of understanding, are common in all facets of computing, and an attacker is always ready to take advantage where value or one-upmanship exists.

Scheduling Gitrob to run periodically on a serverless technology like AWS Lambda [10] to check your repositories periodically would be a very wise move. As you develop and mature the signatures, strings, and filters you are validating with Gitrob, and potentially with other tools or your own scripts, you won't have any excuse to miss the accidental typos or faulty design decisions.