Forensic main memory analysis with Volatility

Fingerprints

When you think of IT forensics, you usually have the analysis of non-volatile data carriers, such as hard disks or SSDs, in mind. But volatile RAM is also worth a look. It usually contains important traces (e.g., of processes or network connections) and thus provides indications of a successful attack.

The detective work is preceded by the task of creating a RAM image. This memory dump must then be analyzed. With Linux onboard tools, users already can find out and learn a lot, but it's also quite a time-consuming process. Luckily, you can find support in Volatility [1], a framework written in Python that identifies the most important memory structures of an operating system and presents the content in a human-readable form. Its big advantage is the many plugins that support a wide variety of analysis activities (Table 1).

Tabelle 1: Volatility Enhancements

|

Plugin |

Function |

|---|---|

|

Processes |

|

|

|

Checks for userland API hooks |

|

|

Extracts the Bash history from the process memory |

|

|

Checks whether processes share credential structures |

|

|

Writes selected memory mappings to a disk |

|

|

Fetches dynamic environment variables of a process |

|

|

Shows the current directory for each process |

|

|

Files opened by kernel |

|

|

Libraries loaded by a process |

|

|

Copies the shared libraries of a process to disk |

|

|

Lists processes with suspicious sockets |

|

|

Looks for suspicious process mappings |

|

|

Shows the memory map of Linux tasks |

|

|

Scans Procedure Linkage Table (PLT) of ELF binaries for unnecessary hooks |

|

|

Prints memory maps of a process |

|

|

Writes the executable of a process to disk |

|

|

Checks for signs of process hollowing |

|

|

Shows processes with start time and command-line arguments |

|

|

Shows processes with their static environment variables |

|

|

Scans the RAM of processes |

|

Plugin |

Function |

|

Kernel and Scheduling |

|

|

|

Checks whether IDT has changed |

|

|

Searches for inline kernelhooks |

|

|

Compares the module list with the sysfs specifications |

|

|

Checks whether the system call table has changed |

|

|

Searches for hooks on TTY devices |

|

|

Browses RAM for hidden kernel modules |

|

|

As with GDB |

|

|

Prints loaded kernel modules |

|

|

Extracts loaded kernel modules |

|

|

Prints active tasks from the |

|

|

Shows processes from |

|

|

Shows parent-child relationships between processes |

|

|

Finds hidden processes |

|

|

Shows the threads of a process |

|

|

Copies a physical address area into an image |

|

Files and Filesystems |

|

|

|

Finds |

|

|

Collects files from the dentry cache |

|

|

Lists file references from the filesystem cache |

|

|

Finds ELF binaries in process mappings |

|

|

Lists files and restores them from RAM |

|

|

Lists file descriptors |

|

|

Prints info on mounted filesystems or devices |

|

|

Lists info on mounted filesystems from |

|

|

Recovers RAM-cached filesystem |

|

|

Restores |

|

|

Recovers cached TrueCrypt passphrases |

|

|

Scans for master boot records |

|

Network |

|

|

|

Shows the Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) table |

|

|

Checks operation function pointers of network protocols |

|

|

Prints active interface info |

|

|

Lists Netfilter hooks |

|

|

Examines network structures |

|

|

Lists open sockets |

|

|

Recovers routing cache |

|

|

Recovers packets from the |

Imaged

The first step is to create a memory image. If the potentially compromised system is running on a virtual machine, the Virtual Machine Manager can create a snapshot, which appropriate tools then take apart [2] [3]. A bare metal Linux presents forensic experts with greater challenges: Every change to the system also changes the memory content, which could destroy valuable clues.

The approach of cooling the memory and reading it out in a special device [4] is not practicable outside a laboratory environment. If the computer has a FireWire connection, a security hole could be exploited, and the memory could be copied over the bus [5]. This has also been described for Thunderbolt and PCIe, but doesn't really work under Linux as of yet [6]-[8].

The only path that remains, then, is to accept that a part of the memory changes while copying. With older Linux versions, this was quite simple, because dd could copy /dev/mem locally to USB sticks, as could netcat over the network. Newer distributions, however, limit read permissions considerably, which is a good idea from a security point of view. Linux Memory Grabber [9] can help you in these cases.

Tapped

The lmg script assumes that a Linux machine is available that can compile a kernel module suitable for the target system; this requires detailed knowledge of the target and a root account. In many cases, forensic experts have to give up here, unless their own system is affected. The instructions on GitHub [9] will help you create a memory image. Although the installation of the kernel module changes the memory content of the target system, and lmg also uses binaries on the target system, which is not entirely without risk on a cracked system, it is probably the only viable solution in most cases.

If you want to be particularly careful about modified binaries, you could bring them along on a USB stick, accept another memory change before installation, and change the path so that the programs from the stick are used. First indications as to whether such a measure is necessary are provided by a host-based intrusion detection system [10]. Linux currently has no particularly secure solutions, such as those proposed in a paper presented at The Digital Forensic Research Workshop in 2013 [11]. Although annoying in forensic investigations, because attackers could also exploit such backdoors, it is definitely a security gain in everyday life.

Forensics

The admin, who now owns a memory image of the possibly compromised computer, can now turn to the analysis. If you want to install Volatility from source, you need numerous Python modules. Alternatively, you can find binaries for popular operating systems on the project page [1]. Simply unzip the ZIP file, and the tool is ready to use. If you find the long name unwieldy, you can create a symlink:

ln -s volatility_2.6_lin64_standalone vol

Also, you should create a profiles subdirectory to give you space for the profiles of the systems to be analyzed. To evaluate a memory image, Volatility requires information about the memory layout. A profile must therefore always precisely match the kernel version. The Volatility wiki [12] links to ready-made Linux profiles and shows how you can use dwarfdump to generate the necessary information about kernel data structures and debug symbols to create your own profiles.

All Set Up

A prebuilt memory image from a book by the Volatility authors [13] was used for all the examples in this article. After downloading and unpacking the ZIP file, you will find a subdirectory named linux with the book.zip archive that needs to be moved to the previously created profiles folder. Whether you use mv, cp, or a hard link is a matter of taste; a symlink did not work on my lab computer. The command

./vol --plugin=profiles/ --info | grep -i book

should return the output:

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6 Linuxbookx64 - A Profile for Linux book x64

If Volatility does not find the profile, the plugin directory may be incorrect. To search several folders, separate their names with colons.

Lazy users can also create a Volatility configuration file, which saves having to type long parameters and lets you reconstruct the settings later. The tool expects its setup either in ~/.volatilityrc or in the current directory in the volatilityrc file. Listing 1 shows an example that defines the plugin directory, a profile, and an image. Alternatively, you can specify the image with the -f switch:

Listing 1: volatilityrc

[DEFAULT] PLUGIN=profiles/ LOCATION=file://AMF_MemorySamples/linux/linux-sample-1.bin PROFILE=Linuxbookx64

./vol --plugin=profiles/ --profile=Linuxbookx64 -f AMF_MemorySamples/linux/linux-sample-1.bin

The order of the parameters is important: If --profile precedes --plugin, the tool will not find the profile. If you specify a path to the profiles in the configuration file, you also need to assign a name for the profile, because command-line options take priority over the setup file.

A Question of Trust

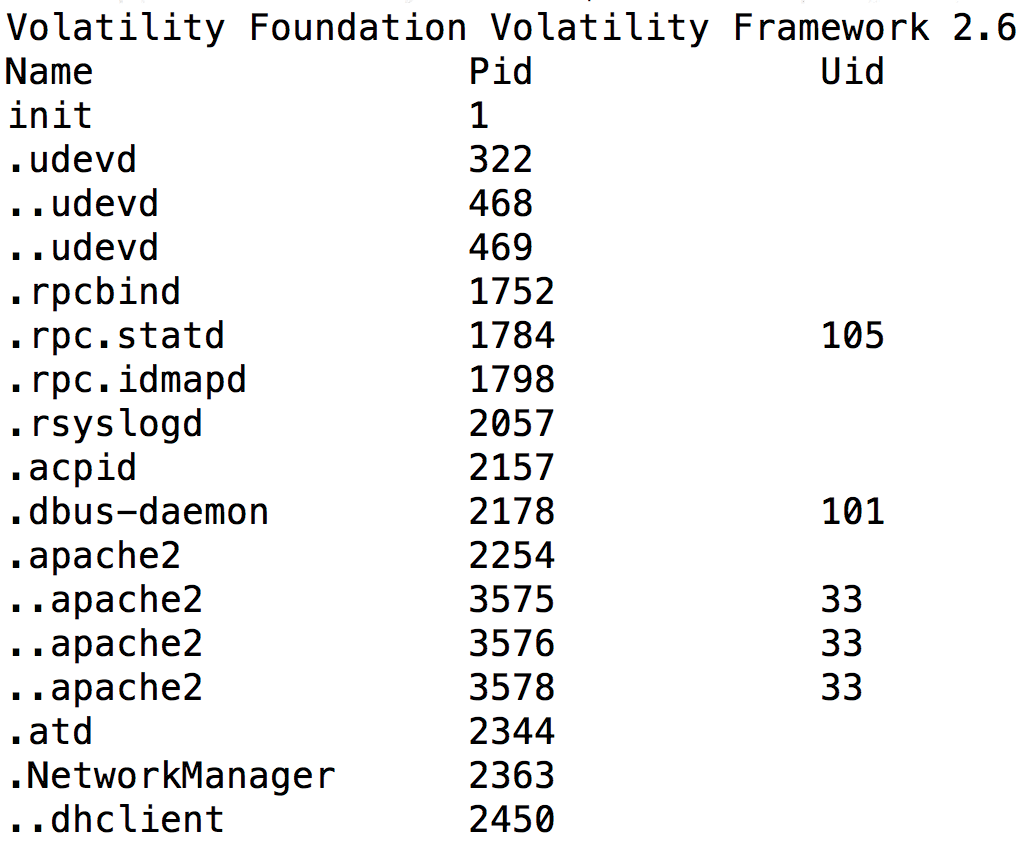

A first look into the memory image with the ./vol linux_pslist command returns a ps-style list. The tool also supports linux_psaux, linux_psenv, and linux_pstree (Figure 1). The lists come from a data structure (defined in sched.h) in which the kernel manages processes.

linux_pstree command is similar to the output generated by the Linux pstree command.Kernel processes are easily recognized because they have no address translation entry in the Directory Table Base (DTB); however, is this output trustworthy? Can an attacker manipulate it? One simple approach to spoofing can be found in the base.c file in the sources of older kernel versions:

res = access_process_vm(task, mm->arg_start, buffer, len, 0);

For each entry in the process list, the kernel reads the shell environment variables. A process that manipulates its environment could therefore appear under a different name.

Because forensic experts must always assume that attackers know the targets at least as well as they do, it is essential to verify the retrieved process list. Volatility offers the linux_psscan command, which does not search the kernel data structures for processes, but the whole memory, where an attacker cannot conceal their actions as easily. Manual adjustment of linux_pslist and linux_psscan is not necessary, because linux_psxview provides a plain text table showing where processes exist.

If you run the commands against the sample image, you will notice that linux_psscan displays numerous processes that linux_pslist does not find. These could be threads that the volatility plugin linux_threads can identify, but an immediately plausible explanation is not always obvious. The swapper process, for example, is missing in both lists, which is certainly allowed as part of the scheduler – it manages idle.

Tracking Rootkits

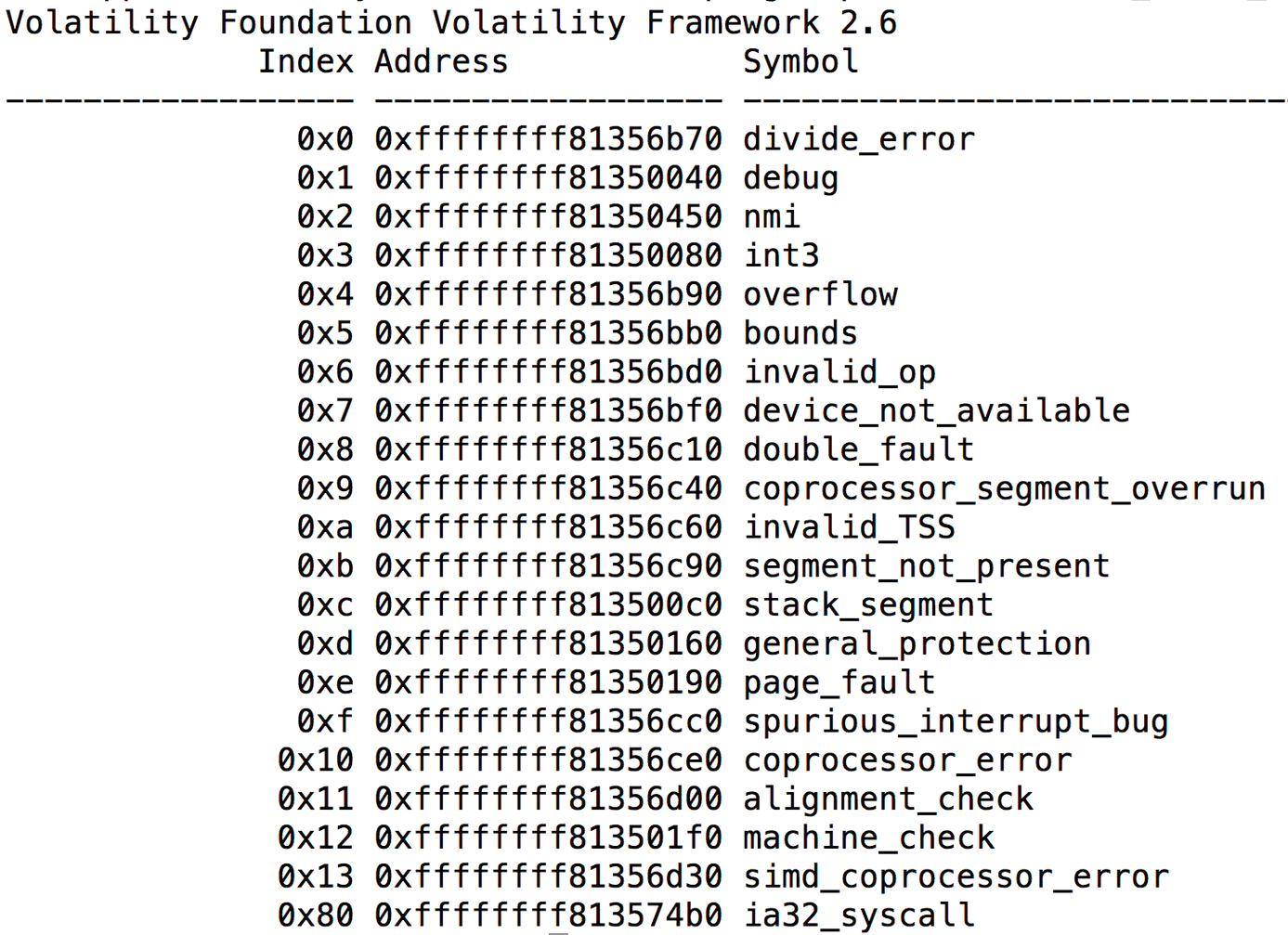

Sometimes it makes sense to create an overview first. Admins who are wondering if a machine is infected by a rootkit [14] can also turn to Volatility. The tool has several plugins that can provide information, including the command

./vol --plugin=profiles/ linux_check_idt

which returns the interrupt descriptor table (Figure 2). If a redirected (hooked) entry is present, the evidence of a manipulated system is strong. The same applies to the exception handlers and the system calls. Just like lsof, linux_lsof looks for the open files of a process; linux_chk_tty and linux_keyboard_notifier check whether an attacker has installed a typical keymapper. Volatility also determines the ARP table, open network connections, mounted filesystems, or kernel modules in use – you can find plugins for almost everything (a complete overview is available in the wiki on GitHub [12]).

Why should an admin resort to Volatility when looking for rootkits and not a special malware scanner that analyzes the disk? A rootkit in memory will not be affected by the check, which increases the chances of discovering the attacker. If a suspicious process is identified, linux_proc_maps returns the memory content for better analysis.

Interpretation Needed

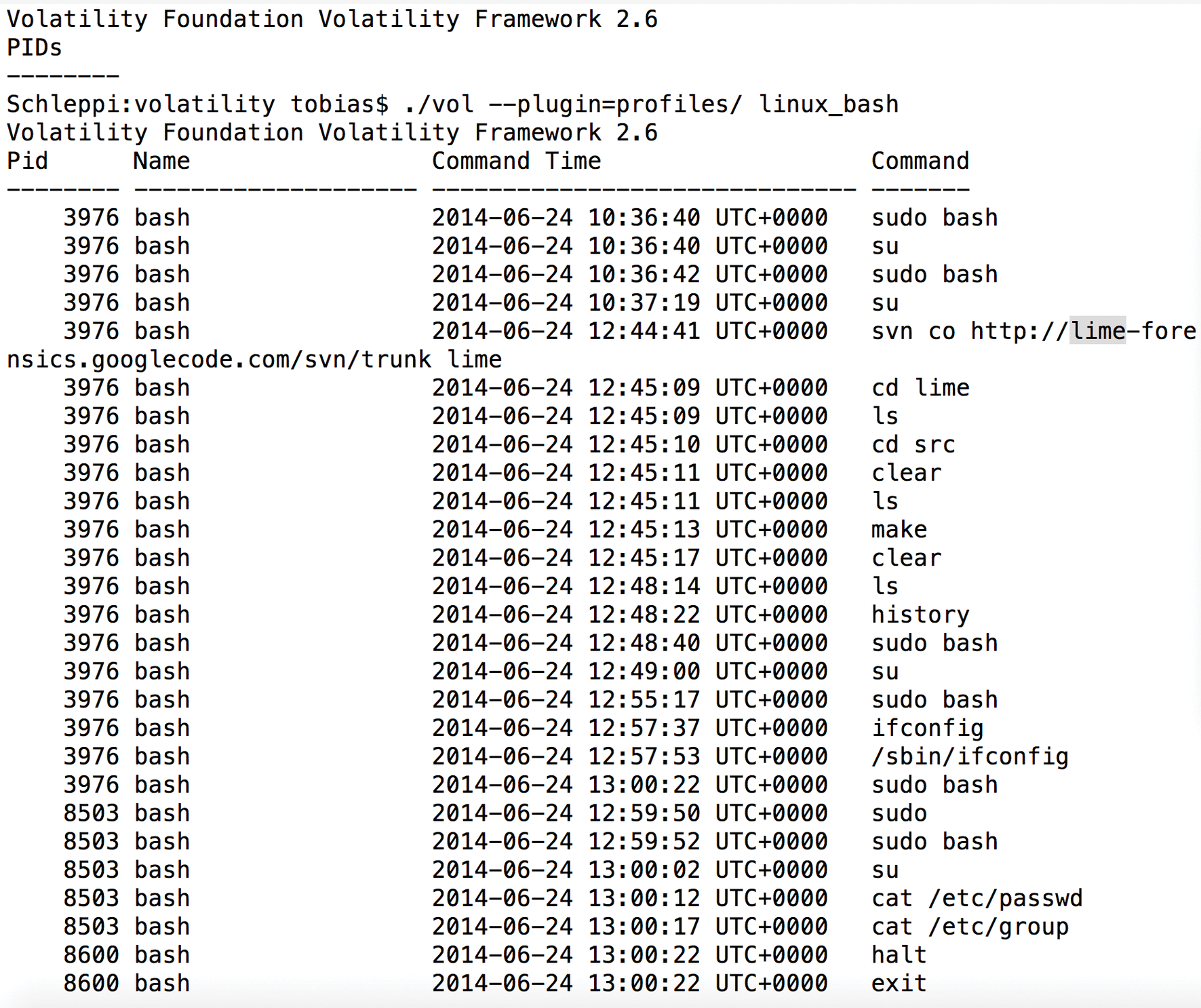

Analyzing the Bash history (Figure 3) is useful for detecting user misbehavior. Volatility also detects commands if the length of the history has been changed to zero and its location to /dev/null to hide the last entries.

lime.The real challenge in using Volatility, as with all analysis tools, is not so much using the correct parameters, but interpreting the program's output correctly. Only practice and a good knowledge of the system with all its data structures will be useful.