Application security testing with ZAP in a Docker container

Dynamic Duo

The Internet has seemingly endless security concerns. The treasures that lie behind some organizations' websites are not only valuable commercially but can genuinely influence the economic development of whole countries if trade or military secrets are stolen. As a result, the number of both automated and expertly targeted online attacks has risen significantly over the last decade or so.

Security professionals have upped their efforts, striving to help create new tools, processes, and procedures to mitigate ever-evolving attacks. As for many items that hold value, seemingly as soon as an innovative defense is created, it is invariably defeated, and its treasures are plundered.

As each new defense formerly thought to be robust is exposed to be otherwise, new attack vectors appear, and offensive security testing professionals adapt their attacks and test their own systems and websites against these vulnerabilities.

The OWASP Top 10 project [1], an "… open community dedicated to enabling organizations to conceive, develop, acquire, operate, and maintain applications that can be trusted," has "injection" as the number one issue in their latest Top 10 report.

In this article, I walk through automating Structured Query Language (SQL) injection attacks in a test laboratory. As with all self-respecting DevOps environments, it's much better to containerize applications for portability and predictability, so I use Docker containers, which also means you can be up and running in a matter of minutes.

SQL injection attacks, or SQLi, are a very popular way to break into websites through badly written applications. OWASP describes such attacks as resulting "… in data loss, corruption, or disclosure to unauthorized parties, loss of accountability, or denial of access. Injection can sometimes lead to complete host takeover." In cybersecurity parlance, the type of offensive testing I'll undertake in this article is called application security (AppSec) testing. (Please see the "Caution!" box.)

To get started, you need an application that's full of security holes, ready to be compromised.

Feeling Vulnerable

As mentioned, modern admins typically don't muck about with virtual machines or build boxes but instead use Docker. After a quick look on Docker Hub for vulnerable applications that run on a Linux/Apache/MySQL/PHP (LAMP) stack, I found a build from OWASP themselves called "Mutillidae," named after a family of wasps [2]. Although I'm a fan of Mutillidae, other applications like WebGoat [3], also from OWASP, offer a highly sophisticated and multilayered insecure web application, as well.

The most suitable Docker image, nowasp [4], appears to be courtesy of user citizenstig on Docker Hub. As a small precaution, I've had a look at obvious issues listed in the image's Dockerfile (Listing 1), but that's hardly something I'd bet the ranch on from a security perspective. Build your own image if you're concerned with its provenance and integrity. The owner of the image tells you how to change the MySQL password, if necessary, on the Docker Hub Overview page [5].

Listing 1: The nowasp Dockerfile

01 FROM tutum/lamp:latest 02 MAINTAINER Nikolay Golub <nikolay.v.golub@gmail.com> 03 04 ENV DEBIAN_FRONTEND noninteractive 05 06 # Preparation 07 RUN rm -fr /app/* && apt-get update && apt-get install -yqq wget unzip php5-curl dnsutils && apt-get upgrade -yqq ca-certificates && update-ca-certificates && rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/* 08 09 # Deploy Mutillidae 10 RUN wget -O /mutillidae.zip https://sourceforge.net/projects/mutillidae/files/latest/download && unzip /mutillidae.zip && rm -rf /app/* && cp -r /mutillidae/* /app && rm -rf /mutillidae && sed -i 's/DirectoryIndex index.html.*/DirectoryIndex index.php index.html index.cgi index.pl index.xhtml index.htm/g' /etc/apache2/mods-enabled/dir.conf&& sed -i 's/static public \$mMySQLDatabaseUsername =.*/static public \$mMySQLDatabaseUsername = "admin";/g' /app/classes/MySQLHandler.php && echo "sed -i 's/static public \$mMySQLDatabasePassword =.*/static public \$mMySQLDatabasePassword = \\\"'\$PASS'\\\";/g' /app/classes/MySQLHandler.php" >> /create_mysql_admin_user.sh && echo 'session.save_path = "/tmp"' >> /etc/php5/apache2/php.ini 11 12 EXPOSE 80 3306 13 CMD ["/run.sh"]

To fire up MySQL with a random password as part of the LAMP stack, use the Docker command:

$ docker run -d -p 80:80 citizenstig/nowasp

If you haven't run a docker pull command for that image before now, the run command will, of course, pull it down from Docker Hub first.

For predictability, you can set the MySQL password as an environment variable within the container:

$ docker run -d -p 80:80 -p 3306:3306 -e MYSQL_PASS="Chang3ME!" citizenstig/nowasp

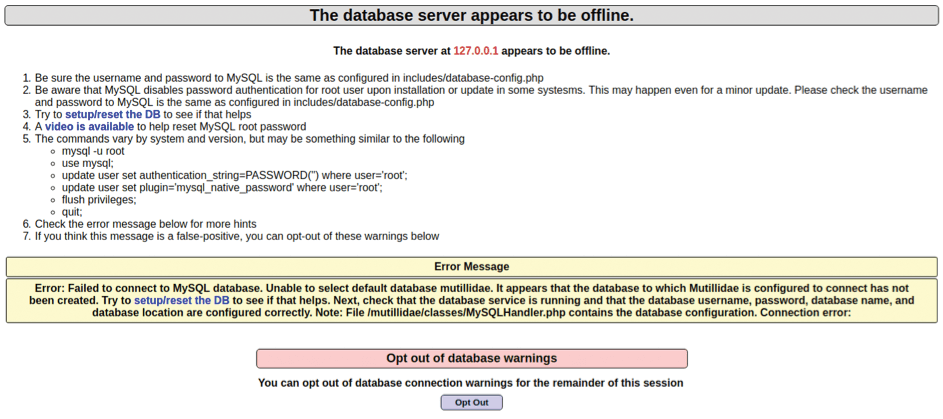

As you will note, you're opening up at least one low-level, privileged network port. Don't be surprised if you have to sudo or become root to run the command. Figure 1 shows that the container is up and running and which ports it's using. When you navigate to http://localhost, however (on TCP port 80 as per Figure 1), you are presented with the unwelcoming error web page shown in Figure 2.

I have to admit when I saw this error, I immediately wanted to dive into the container to fix the issue. First, I grabbed the container hash from the docker ps command and inserted it into the command:

$ docker exec -it 8290c2f0147c /bin/bash

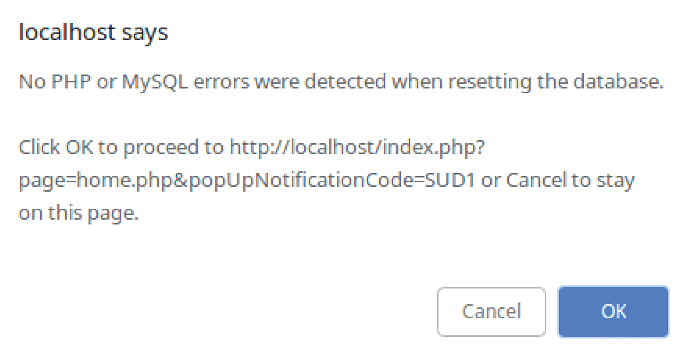

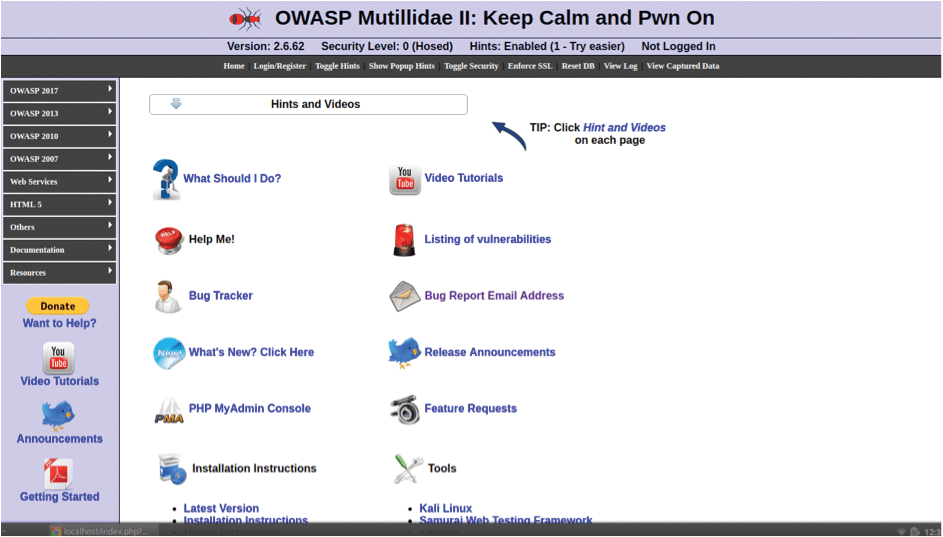

However, instead of looking for the location of the database config file and entering the password for DB_PASSWORD, I just clicked the setup/reset the DB link on the error web page, and two seconds later, after a pop-up dialog box that needed an OK button clicked (Figure 3), the vulnerable application was visible. Figure 4 shows the good news. If you do like rummaging inside containers, then Listing 2 shows you how to reset your MySQL password directly from the command line.

Listing 2: Resetting the Password

$ mysql -u root

$ use mysql;

$ update user set authentication_string=PASSWORD('') where user='root';

$ update user set plugin='mysql_native_password' where user='root';

$ flush privileges;

$ quit;

A Dog with Two Tails

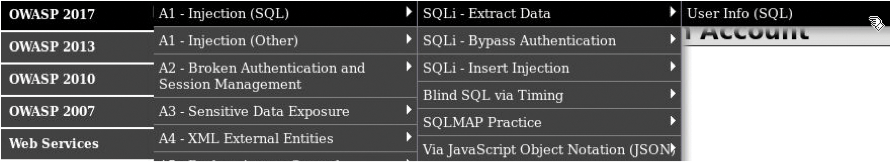

Now that you're up and running, as Mutillidae suggests: "Keep Calm and Pwn On"! To start, click the Login/Register link in the menubar. The very clever Mutillidae is designed around training users about AppSec and offers hints and videos throughout. Note that you will not test against the startup page; instead, from the left sidebar, go to OWASP 2017 | A1 Injection (SQL) | SQLi Extract Data | User Info (SQL). Later, I'll simply provide a URL to reach that page.

Nothing is unusual about the login page shown in Figure 5. These two HTML input boxes are visible on millions of websites all over the web.

Next, you'll need a tool to attack the vulnerable application. As you might have guessed, OWASP has a super-clever tool in its arsenal for just that task, which I wrote about in an earlier ADMIN article [6]. The venerable tool in question is called OWASP Zed Attack Proxy (ZAP) [7], and it acts, as the name clearly suggests, as a go-between proxy that allows you to speak to a remote or other machine and try different attacks.

Should I remind you again about the damage such attack tools can do? I'd even go so far as to say that because you're running a vulnerable machine locally or in a virtual test laboratory, you should disconnect from the Internet, so it's not attacked by someone else (which is easy because it's so vulnerable) and infects your other machines without your knowledge.

Retread

Having pointed you at my previous ZAP article, I'm going to shamelessly reuse some of the commands introduced there. First, you need to fire up a ZAP Docker container and then use an old-school tool called xtightvncviewer to create a GUI through which to access ZAP.

To install the TightVNC viewer package on a Debian derivative, enter:

$ apt install xtightvncviewer

To create a non-persistent Docker container that provides ZAP functionality and a few other useful bits and bobs, as you'll see in a moment, enter:

$ docker run -u zap -p 5900:5900 -p 81:8080 -i owasp/zap2docker-stable x11vnc --forever --usepw --create

The container will stop running if you hit Ctrl+C or close your terminal window.

Incidentally, if your local CPU or I/O is struggling with any Docker images in this article, you might cause less load on your system by running the

$ docker pull <imagename>

command first to download the image, without running it straight away. (It seems to help my machine a little.)

Once your container has fired up, you will be prompted to enter a simple password, so you can access the GUI via TightVNC. Just ignore the odd-looking stty: 'standard input': Inappropriate ioctl for device error. Again, if it's the first time you've run ZAP, you'll be waiting a little while for the image to appear locally after being downloaded from Docker Hub.

The default port is TCP 5900 for TightVNC, so you won't need to adjust the port, just connect to ZAP's internal IP address with the command:

$ xtightvncviewer 172.17.0.3

You can easily get the IP address on which ZAP is listening with the command that follows. Use a second terminal window to run ZAP with the command above and then another window to get the IP address below, if needed:

$ docker inspect -f '{{range .NetworkSettings.Networks}}{{.IPAddress}}{{end}}' <container-hash>

Simply replace the ZAP container hash (found with the command: docker ps) to see your running containers.

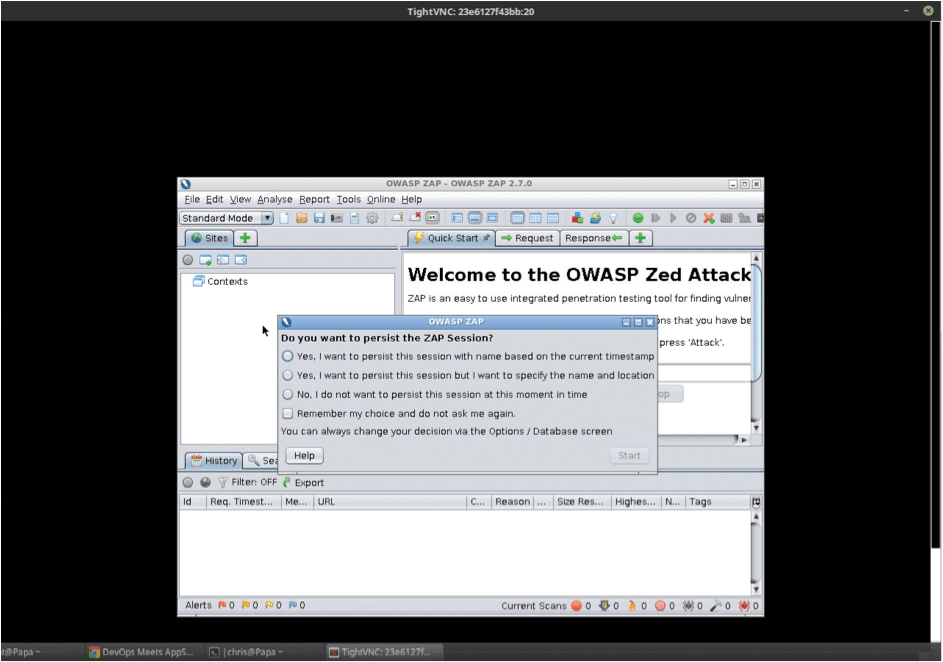

Connect now using the TightVNC command to ZAP's GUI. After some output flying up your ZAP terminal window, once you've put your password in, you should see the result (Figure 6).

What Is This?

Now that you can run ZAP against your victim (sorry, "target") machine, maximize the application inside the TightVNC window to full screen so you can see it more clearly; then, make a choice about whether you want to save data from your session (a reminder that your ZAP container as it is will shut down unless you make it persistent) and then click Start.

For the target, use your Mutillidae container's IP address or localhost. You can get the IP address of Mutillidae in the same way you learned ZAP's IP address by running the docker ps command and then the docker inspect command, altering the hash to that for the Mutillidae container.

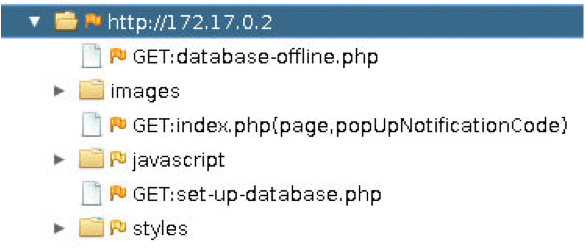

In my case, that means I'll be pointing ZAP at http://172.17.0.2 for Mutillidae (that address is usually the same internally for the first container that's launched, so it's not unusual to see a .2 suffix as the last octet if you started Mutillidae first).

If you're new to proxying through tools like ZAP, you'll probably be pleasantly surprised to discover that inside your container you can even launch a fully fledged version of Firefox to make setting up the proxy easier. Outside of a Docker container, you can also find Firefox plugins that are worth trying in desktop environments if you're keen.

To get the browser working, go to the upper right-hand side of the main Welcome pane, adjust the browser to Firefox (Figure 7), and click Launch Browser. Choosing Chrome doesn't work for me, and the JxBrowser choice sometimes gave me errors, so I went with Firefox.

You should see more output in your ZAP terminal window: Low and behold, Firefox appears. Now pop the preferred SQLi login page URL I promised earlier (http://172.17.0.2/index.php?page=user-info.php) into Firefox, and ZAP will record all the things it sees as it loads the page.

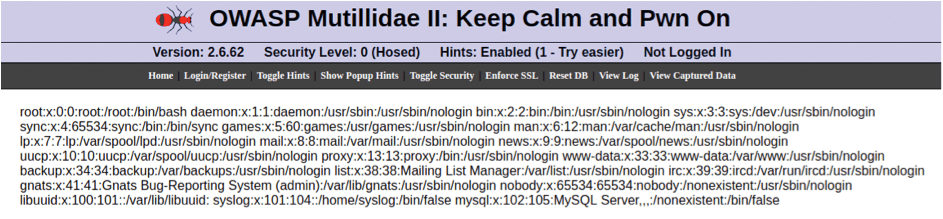

Now you're ready to look at how an attacker thinks in more detail when trying to undermine your application, and therefore its database server. In the following simple example of an attacker sending a crafted URL, the intention is for the server to open a file on the hard drive and display it through the application.

The nasty URL, http://172.17.0.2/index.php?page=%2Fetc%2Fpasswd, should indicate which file is being requested from the server. The result of running such a URL against Mutillidae is shown in Figure 8.

/etc/passwd file for scrutiny.Check It Out

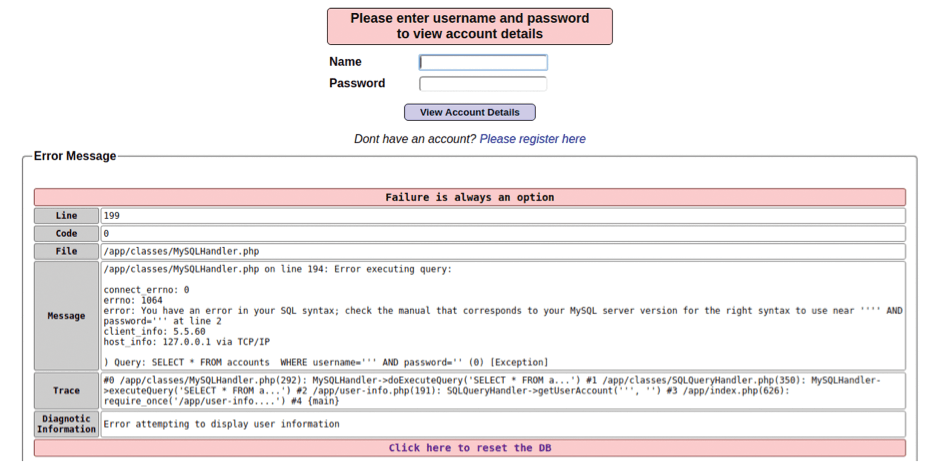

A forward slash in the crafted URL is encoded by %2F, which should get you thinking about how a computer interprets user input. One simple way to test whether a web application is vulnerable to SQLi is to populate an input field (e.g., the login page in Figure 5) with a single quote (apostrophe). If you look below the input boxes, you can see a large amount of SQL being returned (Figure 9). Note the SELECT * FROM accounts … line in particular.

Essentially, the single quote has confused the application enough to display detailed errors; ultimately, that means that it is not validating its input correctly. A single quote was interpreted as valid input, for example, and revealed the existence of a database table called accounts, among other things. That simple, single quote, then, broke the SQL command, confusing the database server as to what was text and what was SQL.

Ready Player One

After having registered a user and password in the database by clicking Please register here, the single quote is added to the end of an SQL command. I know this because after I registered chris and chris as the username/password combination and then added a single quote to the end of the password, I received the error:

SELECT * FROM accounts WHERE username='chris 'AND password='chris'' That's two single quotes at the end of the line and not a double quote or inverted comma.

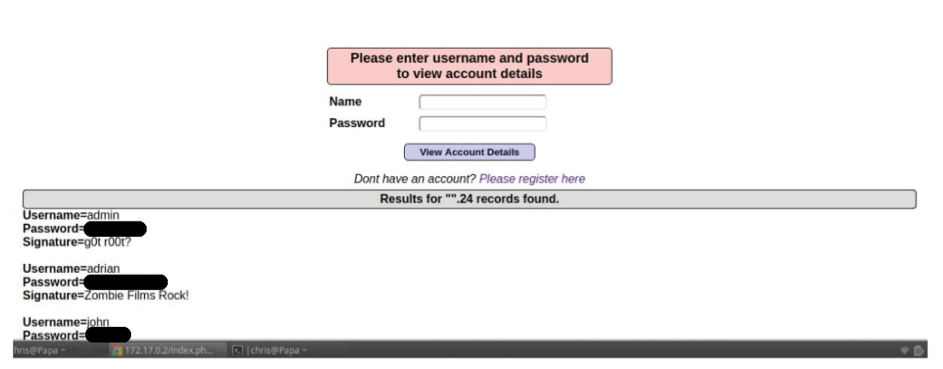

If I craft some more data to put into the password input box that changes the way the database server interprets my password, it might SELECT * – that is, display everything in the database table that's called accounts.

To test this, go back to an empty login screen and enter the password

' OR 1='1

with no username. Expect an extra quote to be added at the end of the line by the database server. The result entering that input is: If everything is empty (in the username and password fields) but number 1 equals number 1, then SELECT *.

The good news for the attacker, but the bad news for the company who owns the application, is shown in Figure 10. The output is abbreviated because multiple users were found. Have a closer look in Listing 3 at what the frighteningly simple, appended string of characters changed.

Listing 3: SQLi

-- the URL that results when user chris logs in --

http://172.17.0.2/index.php?page=user-info.php&username=chris&password=chris&user-info-php-submit-button=View+Account+Details

-- the URL that results from the string of characters that includes the single quote (' OR 1='1) --

http://172.17.0.2/index.php?page=user-info.php&username=&password=%27+OR+1%3D%271&user-info-php-submit-button=View+Account+Details

Note that most sites hide the data in the URL using an HTTP POST rather than an HTTP GET, which will reveal submitted information on the URL, but Mutillidae shows the inner workings on the address bar of the browser.

It's worth saying again that this isn't a database problem per se; rather, the application isn't parsing user input correctly (or maybe more accurately, strictly enough), which means a dump of all the data available from the database matching SELECT * is extracted.

I Spy

Now that you know a bit more about what SQLi might look like, I'm going to make use of ZAP's automated tests to look for them. To begin, open Firefox inside ZAP's container and browse directly to the Mutillidae IP address and its HTTP port (http://172.17.0.2).

To offer ZAP as many of the Mutillidae pages as possible, you need to browse some of the pages beforehand by navigating to any login pages you can find and then registering a new user and logging in. Because the focus is on SQLi, choose the display options from the left sidebar (Figure 11), then register, and log in, moving between other sections of the site once in.

Having explored for a couple of minutes and proxied the site's pages through ZAP's Firefox, you then select the Mutillidae IP address from the left sidebar under the Sites pane in ZAP (Figure 12). Now that you've filled up ZAP with some SQLi pages and highlighted http://172.17.0.2 in ZAP's Sites pane, you can right-click and choose Attack | Active Scan | Start Scan.

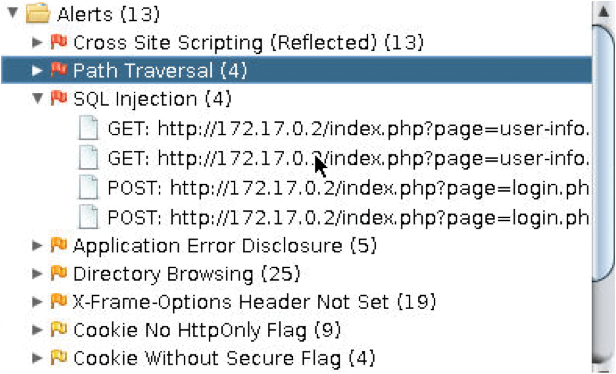

The scan takes a little while to complete (perhaps a few minutes), because ZAP is busy checking all sorts of attack types. While the scan is running, you can keep an eye on the bottom left of the ZAP window for red, orange, and yellow alerts, which let you know what findings of significance have been captured and are worthy of further inspection.

Once it's completed, you can take a peek at the Alerts tab in the bottom pane (Figure 13). If you had run an Active Scan without first visiting login pages, registering users, and logging in, you would have had fewer than the four SQL injection alerts shown here.

login.php and not user-info.php.A Little Fuzzy

An interesting methodology called fuzzing generally involves throwing a bunch of intentionally obscure data at an application to see if it panics or lets you break it in some unceremonious way.

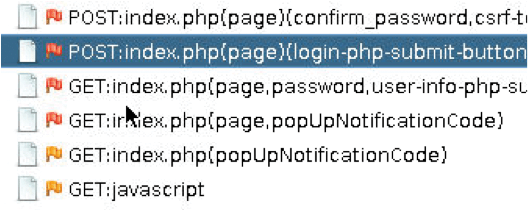

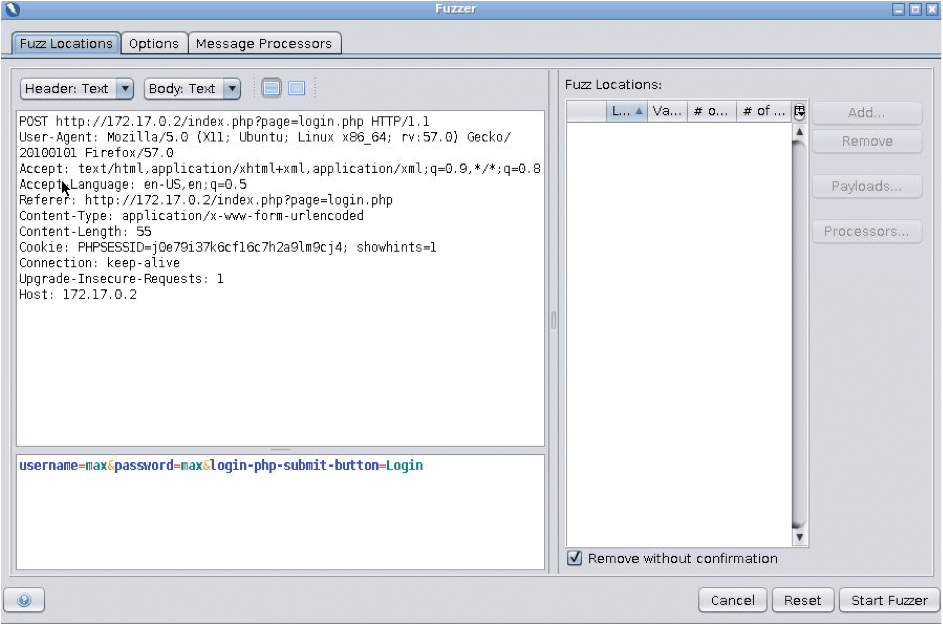

From the four SQLi alerts, choose one of the login.php pages displayed in Figure 13 by looking at the Sites pane and choosing the page shown in Figure 14, mentioning the login submit-button. Having highlighted that entry, right-click and select Attack | Fuzz. You can see in Figure 15 that I tried to log in with the username and password max when proxying login pages through ZAP.

login.php entry with submit-button.

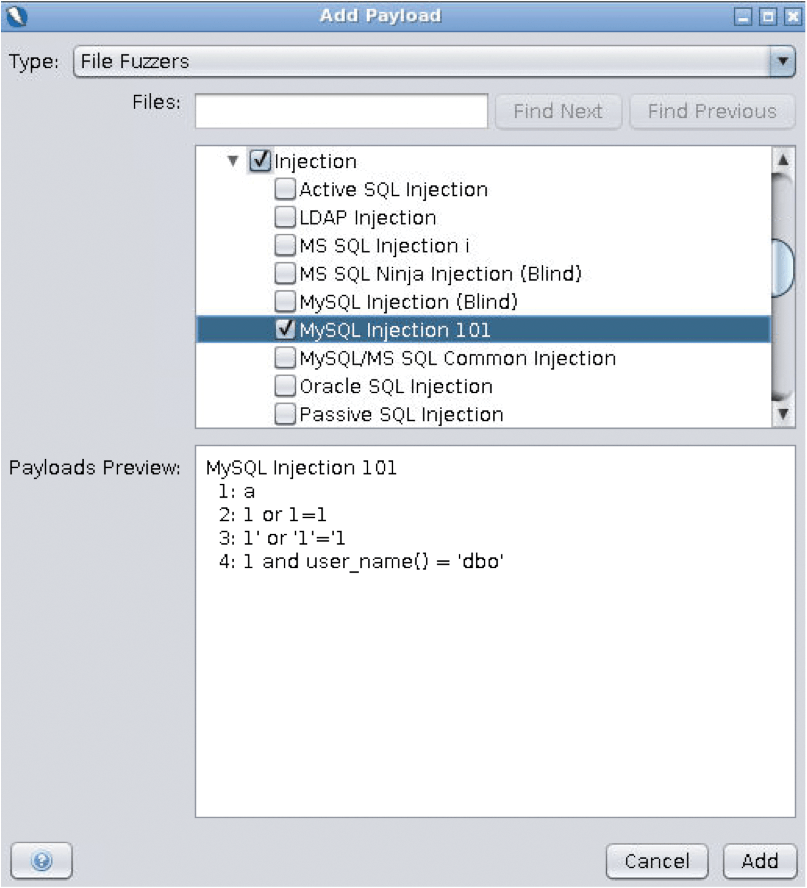

The next task is to highlight the username in the lower pane. Once max is selected, you can add some fuzzing tools by clicking Add and then Add again in the Payloads window. On the Type drop-down menu, select File Fuzzers and expand the jbrofuzz list, and then select the Injection and SQL Injection parent checkboxes (Figure 16) from the visible entries (so that all the children are selected automatically underneath; you can check that they are selected, as well, by expanding these lists). You can see in the pane below some of the detail offered by ZAP about individual scans.

After clicking Add in the Add Payload window and OK in the Payloads window, you're ready to hit Start Fuzzer in the Fuzzer window.

While it's running, you can see that some results in the Fuzzer tab have the Reflected status in the State column, which means that the application has returned your original payload back to you in its response – sometimes this can be of interest.

Great, Smashing, Super

A closer look at the bottom pane in ZAP shows how powerful it is. If you move the fields around a little and pull the columns to the left, so you can view the Payloads column with greater clarity. Inspecting the Size Resp. Body column shows scans that returned a notable response, which was maybe a number of bytes obviously larger or smaller than other HTML page sizes being sent back. I will leave you to explore the results yourself and pick a simple example or two to prove that ZAP has done its job properly.

In my hunting, I spotted an HTTP 302 error that reports Found in the Reason column. This caught my eye because the Size Resp. Body column said 0 bytes; additionally, the Round Trip Time column (RTT) is larger in milliseconds than most of the other responses. As a result, I'd guess that something happened when the code was injected into the application, and a bigger page or a new page entirely was served to the browser (ZAP in this case) as a result.

The SQLi Payload I'm looking at states this string was used to generate the response:

admin' or '

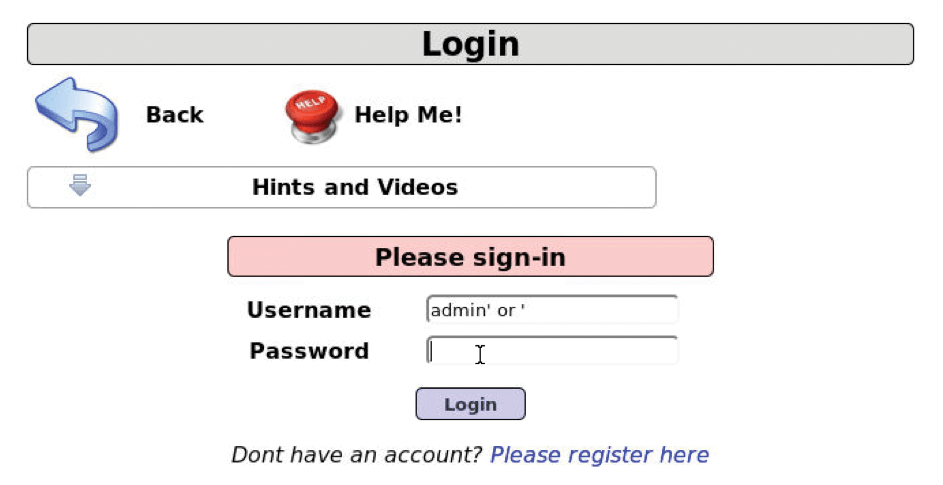

You can try this yourself, as in Figure 17, with the familiar trailing single quote or apostrophe to cause confusion between text and SQL. Populating the Username field while leaving the Password field empty, click the Login button.

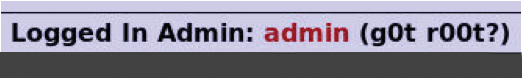

As surmised, a new web page loads and, low and behold, on the top right-hand side of the new page, Mutillidae cheerfully states (Figure 18) you have root user access! Game over.

Doomed!

I hope you've enjoyed taking a very quick look at SQLi with the use of Docker containers. More to the point, however, I hope you're now sufficiently frightened enough of the freely available tools that anyone can get their hands on to put your application through its paces.

Within the right laboratory environment (a reminder that ZAP can attack and potentially break an application) these portable containers are an excellent way of checking that you've ticked lots of security checkboxes while developing your software.

I've only looked at a tiny corner of ZAP's functionality, and I'd encourage everyone to get their hands dirtier and learn more about defending against these offensive security testing tools.