How open source helped CERN find the Higgs boson

Boson Buddies

CERN is on its voyage to uncover the secrets of our universe. One of the biggest discoveries at CERN, besides the creation of the web, was the Higgs boson [1]. However, that discovery was not an easy feat. The Higgs boson lasts only for 1 zeptosecond (zs), the smallest division of time measured by humankind [2]: that's a trillionth of a billionth of a second (i.e., 10^-21sec). The discovery required super-advanced sensors to collect data from particle collisions; then, a massive infrastructure was needed to store and process the continuous stream of data generated by these sensors.

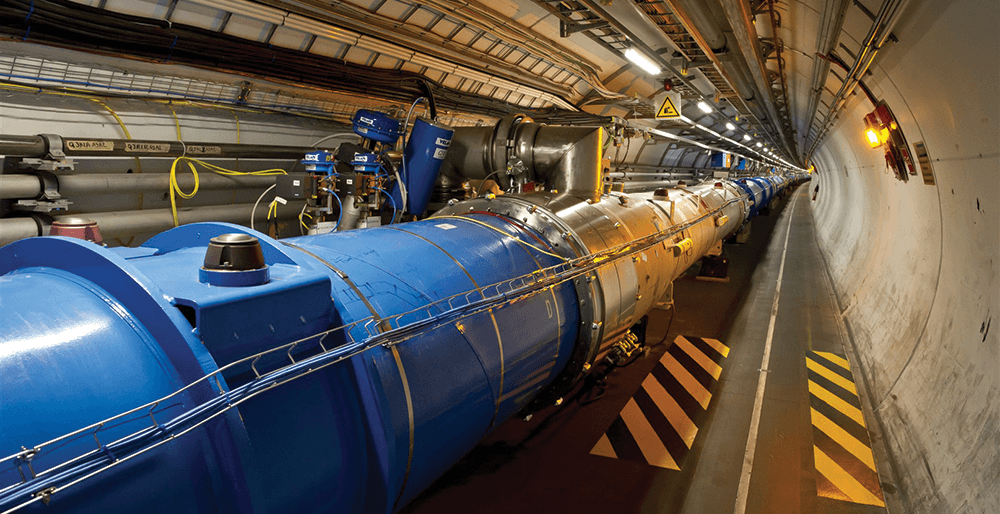

CERN has built massive machines like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) that weighs more than 7,000 tons and spreads across 27 kilometers in Europe. More than 9,500 magnets in the collider accelerate the particle beams at almost the speed of light. The LHC is capable of creating up to 1 billion collisions per second – and it's going to get bigger. CERN is planning a massive upgrade with the High-Luminosity Large Hadron Collider (HL-LHC) project that will produce a 10 times increase in the amount of data between 2026 and 2036.

How much data is it in numbers? The sensors of a cathedral-sized collider generate more than 1PB of data per second, and it's only going to increase. Collecting, storing, and processing this amount of data creates unique challenges for CERN not seen anywhere else on earth.

To better understand these challenges, I sat down with Tim Bell, the group leader of the Computer and Monitoring group within the IT department of CERN. Bell is leading a team that manages the computer and monitoring infrastructure at the data center. He is also an elected member of the OpenStack Foundation board, which allows CERN to keep up with what's going on in the industry.

"One of the aims of the CERN collaboration with industry is to make sure that the things that we're doing are relevant to industry and have applications in that environment. It's a way of us giving back," said Bell.

Challenges of Galactic Scale

The kind of work CERN is doing poses some serious computing challenges. In terms of the cloud, which is needed to manage data, the challenges are in three areas: compute, networking, and storage.

"I think at the moment, when we look at where we need to be going forward, storage is probably a more complex system than the compute," he said. "The compute models have been worked out over the past decades, and although virtualization has changed our efficiency in delivering that because we're now able to be software defined, storage areas remain a problem as we start to see the spinning disk capacities flattening out. How do we address the potential of 60 times increase in storage within the next five years is one of the worries. We have to find the right balance between tape storage, which is cheap, but it takes a while to get at, and disk storage, where we have a fast capacity, but it's a more expensive medium these days."

Large Container Collider

To collect, store, and process the data created by LHC sensors, CERN is currently running a massive cloud with about 320,000 cores and around 9,200 hypervisors; it's called CERN Cloud. "We will gradually continue to expand that, adding more of the bare metal side of things," Bell said. Open source technologies like OpenStack power CERN Cloud.

Looking at the scale of its operations, CERN can't rely on its own cloud; they have a very clear-cut multicloud strategy. CERN is already working with 170 universities and labs across the world and using their resources, but when needed, CERN also exploits public cloud resources. It uses its on-premises CERN Cloud, T-Systems Cloud (a subsidiary of Deutsche Telekom), and Google Compute Engine. "At this point, we have started to investigate container technologies – in particular, the ability to run physics applications in containers," said Bell.

CERN uses OpenStack Magnum, which primarily provides a Kubernetes cluster with a single command line to orchestrate containers running on these clouds. CERN has already built the capability to run physics analyses on top of the CERN Cloud using federated Kubernetes across multiple clouds.

Bell is particularly excited about the whole movement around Kubernetes as a federation vehicle. "It's really transforming the way that we're thinking about how we deploy services for the future," he said. "The idea that we can use Kubernetes to hide from the end users where we're provisioning resources. It allows us to utilize public cloud during burst activities better and then quickly scale back to using the on-premises resources."

Collaboration

Another massive science project that operates at the scale of CERN is Square Kilometer Array (SKA) [3], an international project to create the world's largest radio telescope. SKA is also using open source technologies like OpenStack. In contrast to CERN, SKA is looking at generating more than 5,000PB of raw data per day. Unlike CERN, SKA telescopes are located in the deserts of Australia and South Africa that pose unique challenges in terms of storing and moving this data around. They are facing unique compute, storage, and networking challenges and betting big on open source technologies.

CERN and SKA are working together investigating four different areas of compute research. "In particular, we are working around preemptible instances, where our aim is to be able to start up virtual machines but then stop them abruptly when there is a higher priority activity that comes along. This allows research clouds to fill up to a large degree of utilization and, equally, commercial clouds, potentially to use their spare elastic capacity and monetize that in a similar way that the Amazon spot market does," he said.

The other area is bare metal container orchestration. "We are looking at how can we be using containers on bare metal rather than the current mode, where we run containers on top of virtual machines, which gives us very nice isolation," he said. "It's interesting to have a mode where you're provisioning through Magnum on top of Ironic, rather than taking them out to the virtual machine pool."

Exploring New Technologies

CERN takes a break of two years to upgrade its systems. The next major upgrade is scheduled for 2019 and 2020. The IT team at CERN is already researching, exploring, and preparing for the upgrade of the computing environment that will start in 2020.

CERN runs a very flat network structure, without any significant amount of tenant isolation. They don't need such isolation, because the data is available to the general public. With the emergence of IoT, though, CERN is now looking at isolation.

"We are starting to now explore some of the more sophisticated uses of Neutron to deploy those for our cloud. We run a basic flat Linux bridge structure, but we are exploring solutions like Tungsten Fabric to be able to produce tenant isolation for the Pension fund, the medical systems, or the surveillance cameras," he said.

CERN is also exploring the possibilities of GPUs, TensorFlow, and other software-defined technologies that can be usable in high-energy physics. They are also looking into machine learning. I thought it would be much easier for CERN to use machine learning to find particles like the Higgs boson. I was wrong.

"A difficulty of using machine learning, in particular, as we start to look at doing research, is that you can't train anything because you don't know what you're going to discover. When you don't know what the Higgs boson looks like, how do you train something to look for the Higgs boson?" he said.

However, CERN is investigating the use of machine learning in many areas. "It's still quite a new technology, and it takes a while to apply this to the research use cases. Since the accelerator is running, the priority is on ensuring that data is recorded and processed correctly. Shutdown periods allow people to have a look at new technologies at that point," said Bell.

But the CERN teams don't wait for these shutdown periods: "We are constantly exploring new technologies, but if we want to do significant change, then at that point, that's when we start to bring it in over that upgrade period, since we aren't faced with the deluge of data coming from the accelerator," said Bell. "During the previous upgrade cycle (2011-2012), we deployed OpenStack; it was a very natural point at which you bring in tools like Puppet and Grafana, which bring significant changes to the infrastructure. But there's constant incremental change. We continue to update our software stack."

The People

You don't have to be a rocket scientist to work in CERN's IT team. It's all about looking at the future. Bell has a team of around 55 people. "When we go out to recruit people, we look for people who are able to adapt and rapidly adopt new technologies. It's not so much about what they have done, it's more about have they shown and demonstrated the ability to learn new technologies," Bell said.

CERN also invites visitors from other universities around the globe and has collaborated with industry players. At the moment, CERN is working on OpenStack with Huawei, which funds some people to work on solving scalability challenges in the LHC. In return, these challenges also help solve problems for the industry; in terms of scalability, LHC is today where the industry will be in the future. "Everything that we do at CERN is contributed back to the project," Bell said.

Inspiring Future Generations

CERN uses its infrastructure to motivate kids in getting excited about science. With the CERN Open Data Portal, children can come and run simulations like physicists. CERN also works with universities and schools so students can learn about the discoveries made at CERN. "We have a very open data policy," said Bell. "We're very keen on open access publishing. People ought to be able to read the results of the papers that CERN have done."

More than 80,000 school kids visit CERN every year. Teachers from different countries are nominated and win prizes to come to CERN. "During summer we welcomed over 200 summer students who came to work at CERN for nine weeks to get a chance to be exposed to the physics and the computing and the engineering," he said. "Next year, CERN will have an open day during the autumn where people can come along and go underground to actually see the detectors up close. There is nothing more impressive than seeing a cathedral-size 7,000-ton piece of scientific equipment."