Preparing to move to the cloud

Jump!

If you believe the advertisements, it's easy to use the services of cloud providers like Amazon [1], Google [2], Microsoft [3], and others. At the same time, the marketing by these companies suggests that the way into the cloud is completely uncomplicated. In fact, moving to the cloud is often a multidimensional challenge. In this article, I highlight some of the hurdles and focus on the non-technical side.

Experts argue about what exactly the cloud is [4], but here, the cloud is understood to provide the capacity to store, transport, and process third-party data – or, in cloud jargon, storage, network, and compute.

Why Move?

Companies that want to move to the cloud should clarify a number of questions before making the switch. Among them: What problems relating to the local IT infrastructure do you expect the cloud to solve? What are the expectations? Which objectives should the change fulfill? Which criteria are important? Can these criteria be measured, and how is the measurement carried out? What happens if expectations are not fulfilled? What are the exit criteria? Moreover, few people think about an alternative in the event that cloud outsourcing does not work as desired.

A professional evaluation requires some research. Among other things, the myths of higher speed and greatly reduced costs in the cloud must be examined carefully – at least for your own use case. Expectations that broken business processes will magically repair themselves outside of your own IT infrastructure are bold at best, but probably misplaced.

I will take a look behind the scenes of a migration to the cloud from four perspectives to answer the question: Should I stay or should I go?

Software

One obvious question relates to software, which can be broken into two parts. The IT department has to consider the business application itself (i.e., the software used by the company to earn money), and it needs to look at the software that works behind the scenes: What technologies are used when it comes to updating, availability, or normal operation?

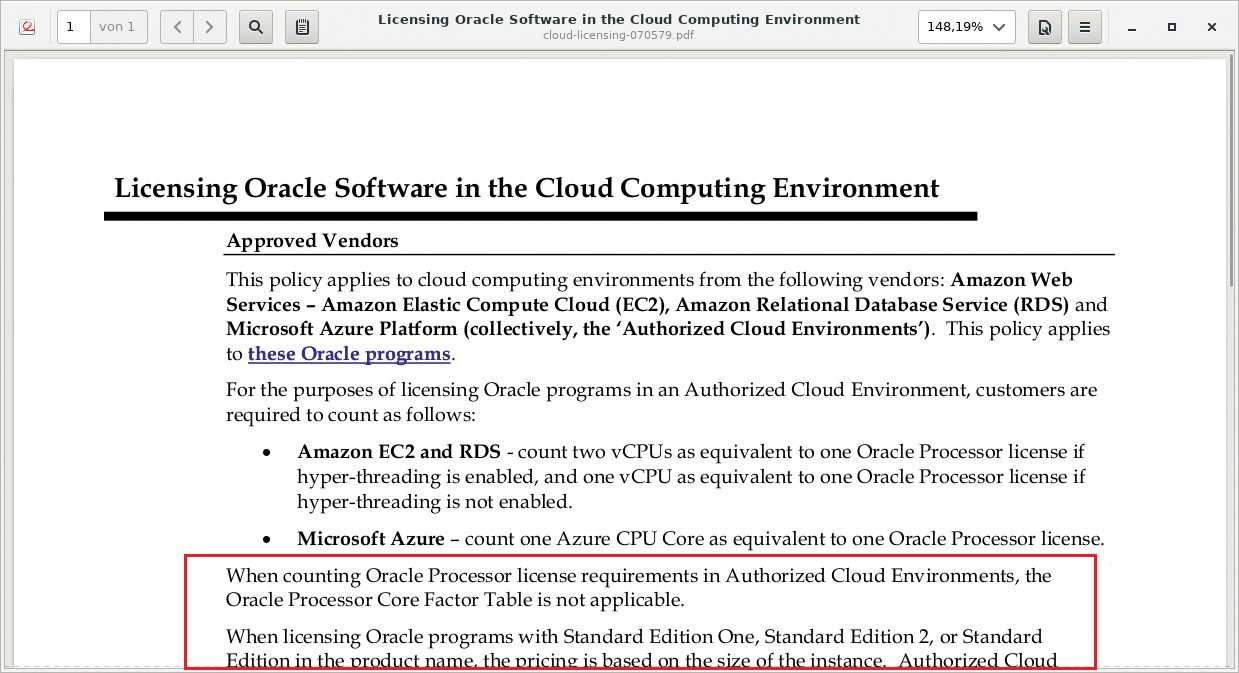

Business software is either a proprietary development or it comes from a third party. In the second case, you need to check whether the contracts allow operation outside the previous IT landscape and, if so, to what extent. Is the license or subscription limited to, say, a certain country, the EU, or other geographical regions or jurisdictions? Could the possibility of unlimited access to the infrastructure by employees of the cloud operator be a problem? Do prices change according to external use (Figure 1)? Does the manufacturer map operations on a mainly virtual infrastructure? These questions only touch the tip of the iceberg.

If your company's business applications are developed in-house, you might be smiling because you would not have to concern yourself with most of the restrictions mentioned above; however, the overall situation remains complex. The central questions are: Does the software also run in the cloud? What does the company do if this is not the case? Generally, you have no valid recourse in the second case.

Alternatively, a "lift-and-shift" application simply runs unchanged on the new infrastructure because the large cloud providers meet almost every requirement: the provision of a virtual or physical infrastructure, a variable number of CPUs, a discretionary amount of RAM, the choice of Windows or Linux, different GPUs, and so on.

Opponents of lift and shift argue that a company gives up many advantages of being in the cloud and would have to face challenges that might be overcome with new development. For example, an interactive approach – possibly via a GUI – often scales less well outside the corporate IT environment and even causes unnecessary costs. Another possible challenge is data handling, but more about that later.

The essential points of cloud operations are infrastructure expectations and contractually guaranteed performance. Only rarely does a cloud user fall back on physically separate hardware, although it might be possible to implement CPU, RAM, and storage outside the cloud.

Availability

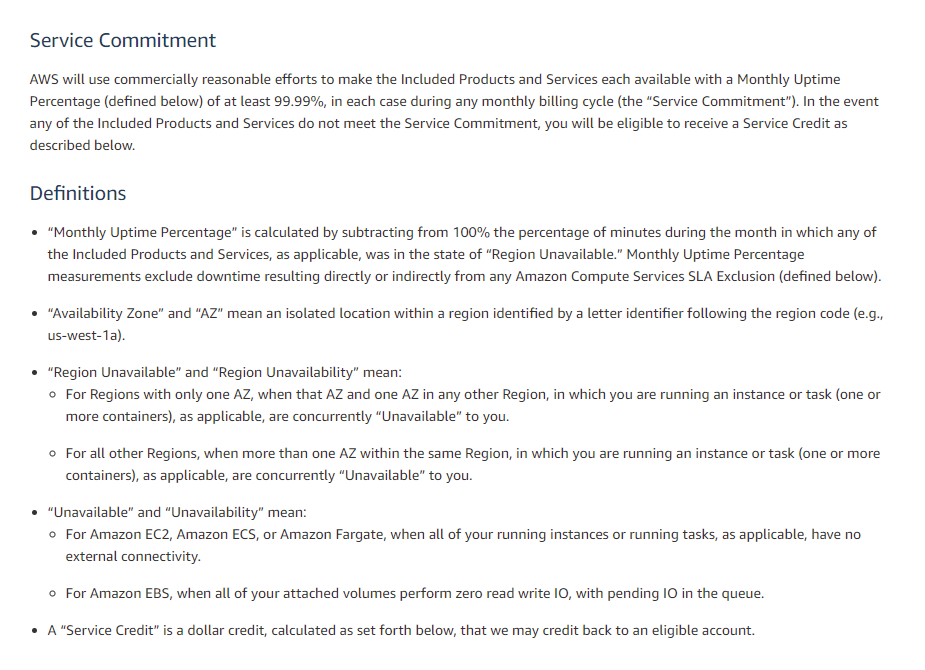

Another aspect is the reliability of the infrastructure, which also requires a thorough reading of the cloud provider's small print. Figure 2 shows an excerpt of the service description for Compute by Amazon Web Services (AWS) [5]. The section shown also includes the definition of regions and availability zones (AZs). If you take a close look, you will see that, from the AWS point of view, the failure of one AZ does not constitute a violation of the service agreement.

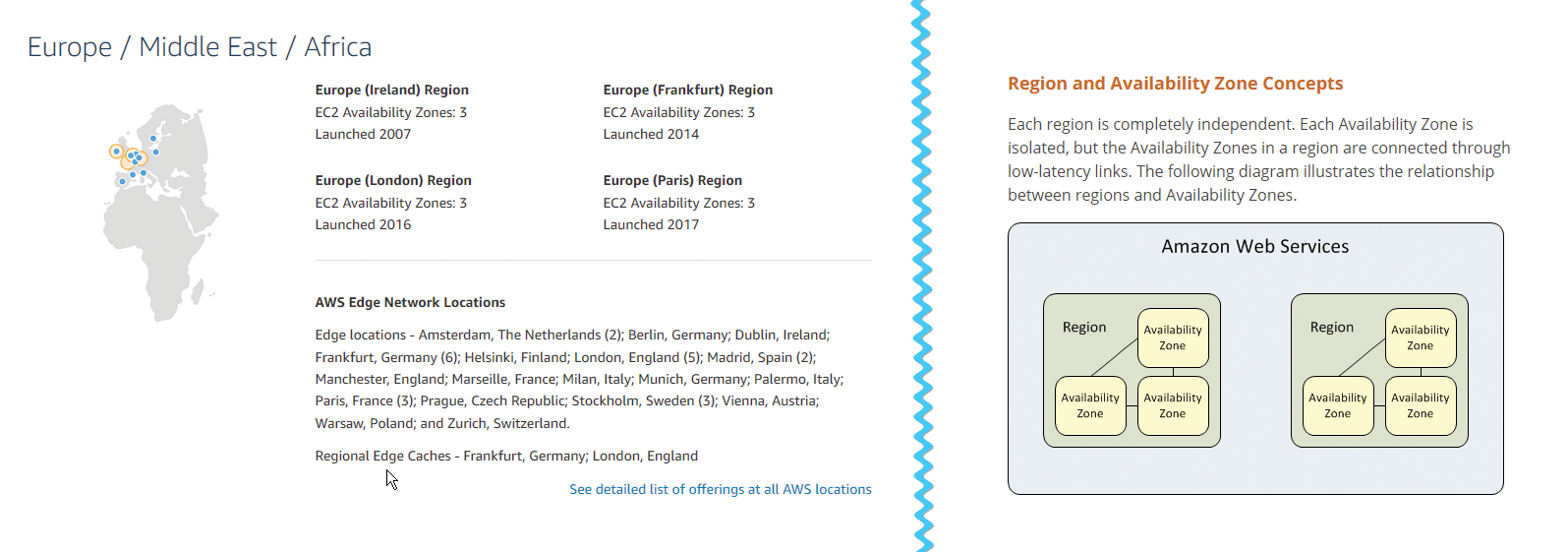

This situation is fatal if the region is small. London, for example, has only three AZs (Figure 3). AWS does not breach its service obligation here until the entire region is out of action, which can be a problem if the software is not allowed to leave the country: With AWS-only resources, the business application would be grounded.

The expectations of your own IT infrastructure will typically be significantly higher. Three small data centers (DCs) located close to each other more or less correspond to the AWS region for London. Normally, the failure of a data center is not a negligible event.

A formal check of whether software or a software provider is suitable for the cloud is useful. A catalog of requirements should include, among other things, the questions already posed to this point, along with a selection and evaluation of possible answers. In the simplest case, you can create a document or a spreadsheet template to evaluate both the existing software and what you intend to purchase.

Depending on the vendor, the requirements can focus on the application manufacturer, rather than the application itself. It is important not to make exceptions, and the criteria in the catalog should be as objective as possible – even if they are specific to a company. This procedure can be easily generalized and extended to suppliers, business partners, and cloud providers.

The challenges presented here are intended to encourage you to prepare the topic thoroughly, not discourage you from setting out.

Data

Another dimension to be considered when moving to the cloud is your data, which exists in different forms, including the intellectual property rights that apply to applications developed in-house, such as algorithms or procedures that have been implemented. As mentioned before, the employees of a cloud provider can theoretically access the infrastructure, so another concern is the extent to which a company can trust the multitenant capability of a cloud technology. With third-party software, it's a little easier; admins can assume that cloud-suitable licenses, support contracts, and subscriptions fully address this issue.

A second category of data includes the information that your application receives, processes, and shares, which could come from your own company or from customers and partners. This category also includes data on the structure, configuration, and topology of the infrastructure and the layers above it.

Possibly, some data is not worth protecting. This decision is rarely binary. Typically, access to data may be (a) intended for the entire public, (b) only for the company's own customers and business partners, or (c) only for the company or parts of its workforce. Further gradations are not unusual.

The nature of the data also plays a role. Does it contain personal information? If so, what compliance legislation needs to be considered? For example, a new European Union (EU) Regulation on General Data Protection (GDPR) [6], which comes into force in May 2018, states that if credit card information is involved, then Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) [7] immediately takes effect.

In the face of such industry standards and laws, a company must understand the breadth of responsibility of the cloud provider and where it ends, how it secures the cloud, and the extent of in-house IT obligations.

Amazon spells out the PCI DSS case when using AWS as a service provider (Table 1 [8]). In addition to these standards, you must consider any contractual agreements or country-specific laws governing the processing, transmission, or storage of certain information, which could require another type of data classification.

Tabelle 1: AWS Shared Responsibility Model

|

Entity |

Responsibility |

|---|---|

|

Customer |

Security in the cloud |

|

Customer data |

|

|

Platform, applications, identity, and access management |

|

|

Operating system, network, and firewall configuration |

|

|

Client-side: data encryption, integrity, and authentication |

|

|

Server-side: data and filesystem encryption |

|

|

Network traffic: encryption, integrity, and identity |

|

|

AWS |

Security of the cloud |

|

Hardware |

|

|

Global infrastructure: regions, availability zones, and edge locations |

|

|

Software: compute, storage, database, and networking |

The availability topic mentioned above can also play a role. For example, if problems occur in a cloud data center in Germany, will a recovery then take place in France, China, or the US? What do you do if the data is not allowed to leave the country, as in the case of the AWS London region described above?

The volume of data also needs to be taken into account. Domestic IT incurs almost no costs for data transfer, which makes savings considerations meaningless. However, data that flows into or out of the cloud requires a thorough analysis of the transit information, which can sometimes be very time-consuming, especially in mature environments. Moreover, data traffic cannot be reduced without changing processes or workflows.

The analysis sometimes also affects the software used. In the worst case, an IT department would have to turn their processes inside out to save, not increase, costs in the cloud. The question of data processing design is therefore also an important point in the catalog of requirements.

Compared with migrating software, preparing to migrate data (categorization, data entry, data flow analysis) is a mammoth task, yet absolutely necessary before you can attempt to join the cloud.

Connected to software is the integration of data analysis and mapping of in-house applications. An existing inventory of the software (a configuration management database, CMDB) [9] should contain this new information. Cloud providers and other service providers only provide limited help in such cases, because a great amount of in-house knowledge is required for this task.

OSI Layer 8

After software and data, perhaps the most frail aspect of the path into the cloud is the human being. Once the infrastructure is in the cloud, it is no longer your own employees who handle firmware upgrades for the hardware, lay cables, and bolt the bare metal into the rack. Who monitors the cooling or takes care of the zoning?

A few traditional jobs in an IT landscape are no longer necessary, and it doesn't look any better in the higher layers of the technology stack, either. The cloud service providers offer ready-made images for various Linux distributions and Windows versions, which are part of the cost of the overall package. Traditional procurement of operating systems becomes superfluous.

These changes explain the skepticism or perhaps even worry that lies along the path to the cloud. Software and decrees cannot solve this challenge. Instead, management must reorganize IT or even the entire company, because an infrastructure-centric approach will no longer work in the future when these tasks are outsourced.

Basically you have two approaches: outsource your own cloud activities to a new company – which makes it easier to set up new processes, approaches, and procedures, regardless of legacy issues – or change the organizational structure. The first case adds organizational overhead (e.g., in human resources) and, worse, risks building a two-tier society. You are only safe if you work for the Cloud Team. Traditional IT is then considered uncool and threatened with extinction.

In the second case, the interfaces to your own infrastructure ideally are similar to those of the cloud service providers so that the focus shifts toward the business application and the customer. Internal IT follows the same or at least similar principles as the cloud provider (i.e., established AZs, regions, etc.).

Reorganization is not just a matter of paperwork, however, even if the disadvantages of the first approach are less important. However, both options open up the possibility of installing new or adapted processes and workflows that let you turn sys admins into cloud engineers, database admins into data scientists, and application administrators into automation specialists. In this way, old roles and positions are dropped and new, future-oriented responsibilities are created.

Some approaches, practices, and methods have proven their value in the context of the reorganization dilemma, including bimodal IT [10], DevOps, two-speed IT, or lean and agile. This variety of solutions suggests that transformation is simple and only the right tools are needed. Quite the opposite is the case, in fact. The focus is on people, employees, colleagues, and bosses.

Conclusions

Now the article comes full circle: What problems with your existing IT infrastructure do you want the cloud to solve? What are the expectations? Which goals do you want to achieve? Far-reaching changes can be implemented more easily in companies if the necessity and the background are clear and sponsors can be found across the organization.

The way to the cloud is possible, but the challenges are not to be underestimated. The motivation should therefore be comprehensible, beginning with your own staff, but also including partners, service providers, and customers. Managing software and data in the cloud requires changes, customization, and a large amount of homework, as well as new processes, workflows, and approaches. The knowledge and experience gained in operating your own IT landscape is useful, but the central component is and remains the company workforce.