Efficient password management in distributed teams

Secure Transfer

Consider the simple case of a web application database that requires authentication. The challenge is to share this secret information in an efficient but secure way and to transmit it automatically at a later date. What is the best way to do this?

Three Approaches

Traditionally, you have several ways to manage secrets associated with an application. The oldest method is probably the use of constants in source code, such as:

var PASSWORD = 'sn4k3oil'

This method tackles the challenge of keeping secret information synchronized between all team members in a simple, although not secure, way.

On the one hand, anyone who has access to the source code is automatically in possession of the secret information – regardless of whether it is necessary or desirable. On the other hand, exchanging keys with this procedure can turn out to be a tedious process, because the source code has to be changed, checked in to a version management system, and redistributed each time. It also makes it difficult to use the same code in multiple environments, such as a development environment and a production environment.

These disadvantages need to be avoided in a more mature alternative by storing secrets in configuration files that are not checked into version control. If you use this approach, you can remove the constants from the source code, but you accept other disadvantages. Without version control, synchronization between team members that was previously feasible is no longer possible. If a team member wants to change their password, they need to inform everyone else about it and find a secure way to do so. Additionally, this procedure results in unencrypted files on clients and servers that users can forget.

Subsequently, a third method has been established to keep secret information away from both the local filesystem and the source code. This method uses environment variables, which are then read out, as in this JavaScript example:

var PASSWORD = process.env.PASSWORD

This procedure ensures that neither the source code nor the filesystem contains confidential information in plain text. Moreover, the code can be configured easily to run in parallel in different environments. However, using the application becomes more complicated – to start it, you must make sure that the values configured by environment variables are available in the run-time environment.

All three approaches presented so far each involve a compromise between the ability to synchronize secrets and secure storage. However, it would be best to use a method that provides a synchronizable and sharable, but nevertheless encrypted, storage space.

Each team member needs to be able to decrypt information from storage. However, this should not require a password that is shared by all team members, because it will cause problems when distributing and changing this password. However, a password-free solution is also possible and can even be built with a few open source tools.

A Trip to GnuPG

One of the tools used is GNU Privacy Guard (GnuPG), the implementation of a public key infrastructure (PKI). GnuPG is best known for encrypting and signing email. When you create a GnuPG certificate, you generate a public and a private key. Different operations of asymmetric cryptography are possible with these keys, and such a certificate includes a unique identifier – the GnuPG ID – used to reference a certificate securely, which will later play an important role.

Information encrypted by one person with the public key of a GnuPG certificate can be decrypted by another person using only the corresponding private key. If a certificate holder shares the public key with others, it is possible for them to send him or her confidential information in encrypted form. As long as the recipient does not share the private key, only they can read their information.

Pass the Password Manager

The second tool used for the intended method of sharing secrets is the Pass [1] password manager. It is essentially a wrapper around GnuPG that lets you encrypt files in a directory with multiple public GnuPG keys at the same time, thus allowing several people to access and decrypt the encrypted files simultaneously in this directory.

Pass uses GnuPG's capabilities to encrypt individual files for any number of recipients simultaneously. For this purpose, GnuPG initially encrypts the file itself with a symmetric key generated on the fly. This is then encrypted for each recipient with their public key and added to the header of the file in this encrypted form. After encryption with GnuPG, the file header contains the information for decryption for each recipient.

The directory containing the encrypted files can be managed, versioned, and distributed easily through a version control system. With the help of Pass, an encrypted pool of information is created in the following sample application without using a shared secret such as a password. Installing Pass is very easy with the distribution's package manager.

The example in this article is a status page that interactively shows statistics for a specific GitHub user and requires a GitHub username and API token, which is the secret information that needs to be protected.

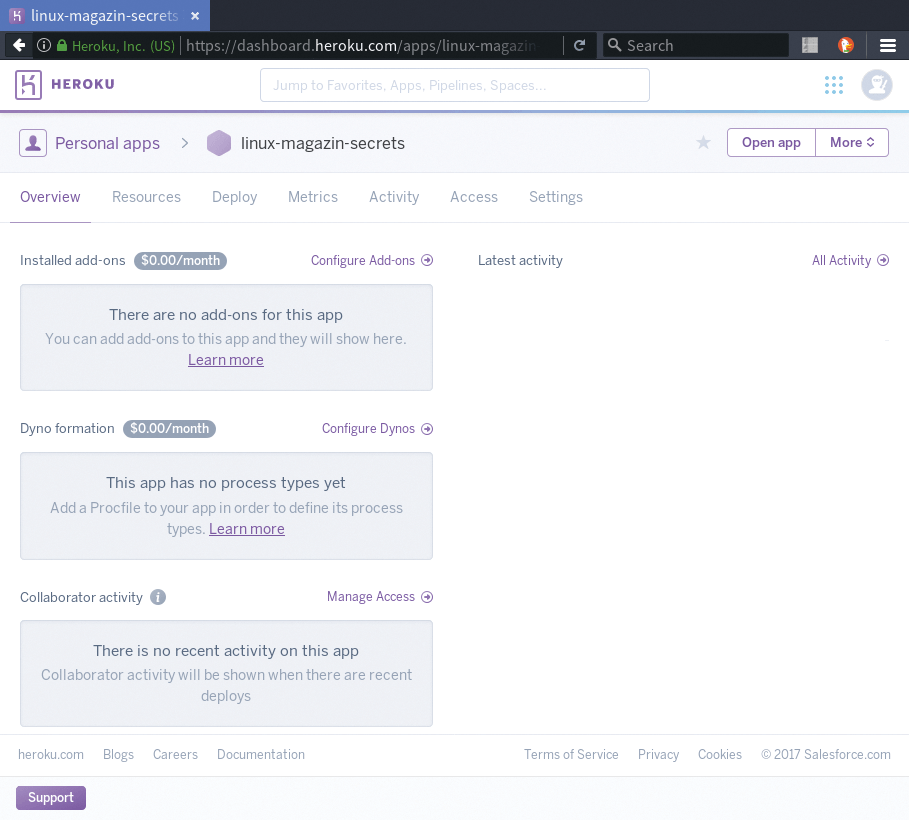

The application itself is written in JavaScript and hosted on the Heroku (Figure 1) Platform as a Service (PaaS) [2]. Because the example uses the existing infrastructure, it can focus on managing secrets.

Heroku as a PaaS Host

By relying on a PaaS solution, you avoid the need to manage either bare metal servers or virtual machines. Everything happens at the application level. Heroku is one of the veterans of the PaaS market and is particularly suitable for simple examples – as in this case.

To start an existing project on Heroku, all you have to do is create an account on the Heroku website, download the Heroku command-line tool, and log in (Listing 1).

Listing 1: Heroku Login

$ heroku login Enter your Heroku credentials: Email: reader@linuxmagazin.de Password: ************************* Logged in as reader@linuxmagazin.de

Before you can run an application in the Heroku cloud, you need a local Git repository that can then be used to register the application with Heroku (Listing 2). The new application is then available online (e.g., in this example under the linux-magazin-secrets name).

Listing 2: Creating an Application

$ cd ~/code/app/linux-magazin-secrets $ heroku create linux-magazin-secrets Creating linux-magazin-secrets... done https://linux-magazin-secrets.herokuapp.com/ | https://git.heroku.com/linux-magazin-secrets.git

The application does not yet have any functionality in this raw version. The next steps add the necessary files to make the application executable.

First, you must create a process definition that describes which processes Heroku needs to start and manage. For a JavaScript application, this step is very simple. The file name must be Procfile and has to be located in the repository's root directory.

The file instructs the platform to manage a service called web. The service consists of a Node.js process that executes the index.js file.

web: node index.js

For the JavaScript application to run on Heroku, it requires a package definition, and it is especially important to define JavaScript package dependencies that the platform automatically installs.

Because the application provides an HTTP endpoint, it requires a web framework. The express.js JavaScript library is suitable and is therefore defined as a dependency in the package definition. This file is also stored in the root directory, but under the name package.json (Listing 3).

Listing 3: package.json

01 {

02 "name": "linux-magazin-secrets",

03 "version": "1.0.0",

04 main() "index.js",

05 "license": "ISC",

06 "dependencies": {

07 "express": "^4.14.0"

08 }

09 }

The server endpoint is located in the index.js file. On the basis of the express.js web framework, it implements an HTTP API endpoint that delivers information about the GitHub user who needs the front end (Listing 4).

Listing 4: index.js

01 var express = require('express')

02 var app = express()

03

04 var user = process.env.GITHUB_USER

05 var apiToken = process.env.GITHUB_API_TOKEN

06

07 var port = process.env.PORT || 5000

08

09 app.get('/', function (req, res) {

10 // Implement GitHub API call

11 })

12

13 app.listen(port, function () {

14 console.log('App listening on port ' + port)

15 })

The application is configured with three environment variables. The PORT variable automatically provides the platform's run-time environment. The convention is that a service must listen on this port to be able to run on Heroku. The other two variables, GITHUB_USER and GITHUB_API_TOKEN, represent the secret information to be provided to the application.

A simple git push deploys the current status on Heroku. The corresponding Git remote repository, called heroku, has already been configured automatically by the previous heroku create call:

$ git push heroku master:master

In principle, this is all you need to get the application up and running. However, because the two GitHub environment variables are not initialized, the application will cancel with an error.

The Heroku command line allows you to set up configurations provided to the application in the form of environment variables. Changes to this configuration automatically restart all services. The two missing variables can be set up with the command:

$ heroku config:set GITHUB_USER="holderbaum" GITHUB_API_TOKEN="sn4k3oil"

This means the target has been achieved; that is, no secret information is stored in the source code or in other files. However, the API token and username must be known to execute the previous configuration command.

Because anything you type into the shell remains in the history for a long time, you should not simply type the secret information there; rather, you should find a secure way to store the secret information and distribute it to the people who are supposed to configure the application. This is where the password manager comes into play.

Directory as a Secret Pool

As already mentioned, Pass is applied to a single directory. To initialize storage of this type, you need to save the directory path in an environment variable, for example, with:

$ export PASSWORD_STORE_DIR=~/code/app/secrets $ export MY_ID=5244D411CD7CBA95 $ pass init $MY_ID

The argument for pass init is the author's GnuPG ID. However, you can also transfer any list of IDs. To keep the example simple, it uses a single ID.

To add values to memory, use pass add. It expects the name of the secret to be added to the memory as an argument and asks via standard input for the actual secret (e.g., the password or API token), which has to be stored encrypted:

$ export PASSWORD_STORE_DIR=~/code/app/secrets $ pass add production/user $ pass add production/api_token

To replay a secret again, use the pass show command. If the calling user is in possession of the private key from one of the certificates specified at init, calling the command decrypts the stored secret and outputs it on standard output:

$ export PASSWORD_STORE_DIR=~/code/app/secrets $ pass show production/api_token "sn4k3oil"

A previous step created a password store that resided in a single directory and was based on separate files. It can thus be easily distributed in a team with the help of a version control system.

The ~/code/myapp/secrets directory now looks like this:

$ find ~/code/app/secrets ~/code/app/secrets/.gpg_id ~/code/app/secrets/production/user.gpg ~/code/app/secrets/production/api_token.gpg

The *.gpg files contain the previously added encrypted secrets. The .gpg_id file contains the list of the GnuPG IDs used to encrypt the memory content.

It is also possible to store more .gpg_id files in subdirectories, so you can implement different access authorizations for different subdirectories. Of course, a tool like find is not needed to list the contents of such memory.

The pass ls command displays the memory tree structure on standard output:

$ export PASSWORD_STORE_DIR=~/code/app/secrets

$ pass ls

+-- production

|-- api_token

+-- user

By combining the passport-based memory with the Heroku command line, the application can be configured without having to enter explicit secrets (Listing 5). This code creates a store for secrets, which allows only one person to access the stored secrets. However, the goal of managing the secrets for an entire team remains.

Listing 5: Variable Configuration

export PASSWORD_STORE_DIR=~/code/app/secrets export USER=`pass show production/user` export TOKEN=`pass show production/api_token` heroku config:set GITHUB_USER=$USER GITHUB_API_TOKEN=$TOKEN

Teamwork

Two scenarios are particularly important for security: roll-on and roll-off. In a roll-on scenario, the trustworthy group of team members is extended by one person, which usually means that the new team member receives certain access rights, such as access to project secrets or infrastructure.

Pass can do this effortlessly: You only need the GnuPG ID of the new member and the corresponding public key. You then call pass init with all the IDs, including the new ones. Pass re-encrypts all information in the store with the public keys of the specified IDs (Listing 6), which is sufficient for accessing the secret store.

Listing 6: Re-Encryption

export PASSWORD_STORE_DIR=~/code/app/secrets export MY_ID=5244D411CD7CBA95 export ADAS_ID=44A7B1E354AF81E2 export ALANS_ID=BA29EE533AF39B21 pass init $MY_ID $ADAS_ID $ALANS_ID

This process can, of course, be repeated for each new team member in the same way. If you want to add confidential data to memory, you need to possess all the public keys that are to be specified during initialization, and it is the only way to encrypt the data correctly when added.

During the roll-off of a team member, the person in question leaves the team and is no longer allowed access to the secrets. This time, call pass init again, but omit the corresponding GnuPG ID.

Again, Pass encrypts all secrets in the store, but this time without the ID that was omitted. It should be noted that the new encryption only means that the former employee is no longer able to decrypt secrets from now on. However, if they keep a copy of the repository before re-encryption, they still have access to the secrets. Therefore, changing all confidential information must be an integral part of the roll-off.

Because Pass keeps the secrets in a central location – the store it has created – it is much easier to manage rotation after a roll-off than if they were randomly distributed across the project.

Conclusions

The example in this article used an encrypted store for secret information in an ordinary directory. This directory can be distributed like source code (e.g., by checking into version control).

Thanks to Pass, entries and exits by team members can largely be treated automatically without compromising security. Access is easy to automate, too, because you can use a simple command at the command line to output any secret directly to standard output.