Manage logical volumes with GUI tools

Fair Serving

Conventional partitioning is reaching its limits with the increasing storage capacity of hard disks and solid-state drives (SSDs). If several physical mass storage devices are attached to clusters or larger standalone servers, you can manage them more conveniently with the Linux Logical Volume Manager (LVM). Even small servers or single-user systems benefit from LVM if you are planning to change a configuration or install additional hard drives in the future.

Well Grouped

LVM adds an abstraction layer between mass storage and its partitions and filesystems. You can thus combine several mass storage devices or physical volumes with LVM in a volume group and then address them as a unit. If only one mass storage device is available, you can set up one or more volume groups on it and then create logical volumes that also contain the respective filesystems. The smallest units of a logical volume system are the physical extents (4MB by default), which are comparable to sectors in classical partitioning schemes.

If you want to add additional mass storage, you retroactively grow the volume groups. The individual logical volumes can grow or shrink as needed, without the need to reconfigure the storage media or recreate the filesystem. It should be noted that the filesystem does not always permit growing and shrinking: Some modern candidates (e.g., XFS [1], JFS [2]) can only grow volumes in the mounted state, not shrink them.

Linux LVM also lets you rearrange data on the fly, which allows hot-swappable configurations, for example, in cluster environments. You can optimize the configuration of your mass storage for performance or safety through different distribution and mirror functions (see the "LVM and RAID" box). LVM Snapshots let you save certain defined conditions and protect yourself against failure.

Disadvantages of LVM

Depending on the configuration, the disadvantages of using LVM include an increased risk of losing data if the system distributes it to multiple devices and one of the disks fails. You should always store data redundantly or make backups in good time. The initial setup is more difficult than with conventional partitions, as well.

LVM on Linux

Linux does not need any special conditions to use LVM, because the operating system supports the functionality (since kernel 2.4). When you install the operating system on single-user systems or small servers, the wizards in all major distributions offer you the option of setting up LVM along with the mass storage. The implementation sometimes causes confusion, though.

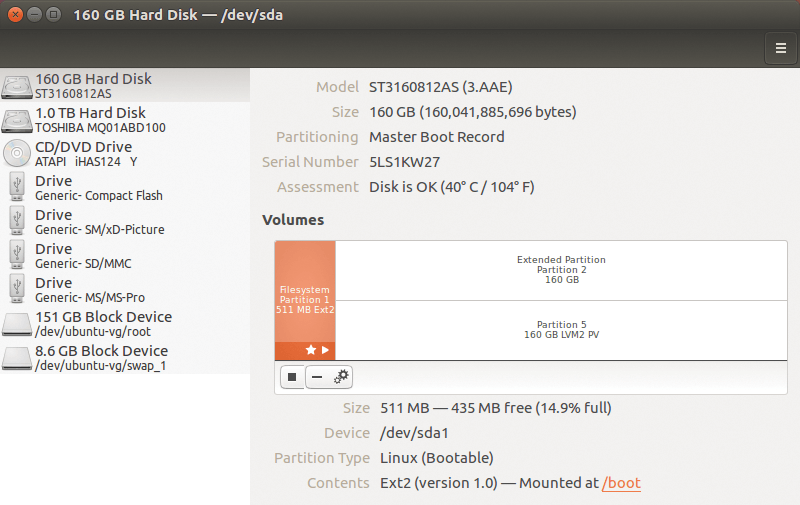

Depending on the distribution, the installer creates different volume groups and physical volumes for data partitions and the swap file. Typically, it also creates a /boot partition that occupies several hundred megabytes on the device. This also happens if you select an unsupported filesystem such as Btrfs from the GRUB boot manager (Figure 1).

You can set up other existing physical mass storage later, if necessary; this also applies to the configuration of the existing storage media. However, the command sequences to be entered at the prompt have many parameters and require training. Graphical tools mainly help LVM newcomers with the software.

In this article, then, I examine a few of these tools in depth, paying particular attention to their practicality in small environments. I also place emphasis on simple operation of the software to clarify whether it can be used without extensive background knowledge.

LVM GUI

Red Hat originally developed LVM GUI for logical volume management [3] in their products, although other distributions also can use this tool, which integrates the system-config-lvm package from the software repositories of Debian, Ubuntu, ALT Linux, and CentOS [4]. On Fedora, it is only in the repositories up to version 24, but you can add it manually in Fedora 25 and 26.

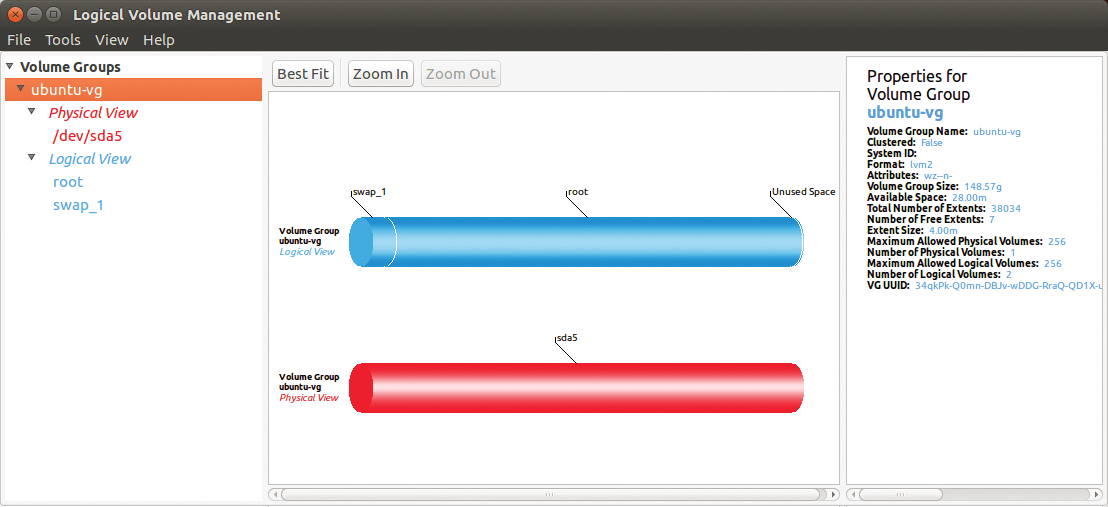

After installing, the Logical Volume Management (LVM) launcher is available in the System menu tree. It calls up a three-part window (Figure 2) for configuration that shows the physical and logical volume groups in a list on the left, visualizes the different groups in the middle, including their usage data, and presents the properties of the individual volumes on the right.

The volume groups are shown graphically as cylinders, with the corresponding block device shown at the center of the window. The physical devices appear again to the left of the window, giving you an at-a-glance insight into the number of storage devices connected to the system and which logical volumes are available. The logical volume groups can be conventional structures, such as the /root and /home directories and the /swap partition.

Below the centrally arranged graphic, depending on the device selected, you will find several buttons for setting up the LVM system. If other storage devices are attached to the system but are not (yet) part of the drive group you set up, these buttons are listed under the Uninitialized Entities heading in the left window segment. You can integrate any number of block devices into the system; it is important to note that the software does not detect classically partitioned and formatted drives. Instead, it expects a volume prepared as a physical volume.

To integrate a drive (e.g., a hot-swappable hard drive freshly installed in a server) into the LVM system, press Tools | Initialize Block Device and enter the device name in the window that appears. The device then appears on the left side of the program window.

Clicking on the device name and selecting the Add to existing Volume Group button at bottom center adds the device to a volume group. In a separate window, you decide which specific group this should be; then, the bar display immediately jumps to the starting position and displays all the available drives.

To remove a physical volume from a volume group at a later time, click on the corresponding device name in the Physical View section highlighted in red on the left side and select the Remove Volume from Volume Group option at the bottom of the window. The software deletes the device from the group after a security prompt.

New Groups

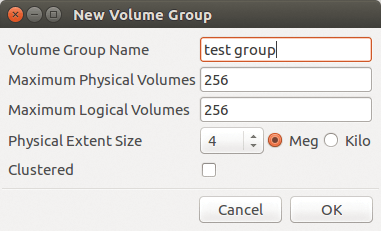

To add entire volume groups to the system requires that the respective devices are already registered with the system but have not yet been allocated. Click on the respective device on the left and then select the Create new Volume Group option at the bottom of the program window.

In a separate settings window, specify the name of the new group and the maximum number of physical and logical volumes that can join the group – 256 is the default. Also specify the size of the individual memory cells here; this defaults to 4MB per unit (Figure 3). The new group, which you can edit later, then appears in the Physical View and Logical View tabs on the left side of the program window.

Before you can actively integrate the group into your system, though, you still need to define logical volumes and configure them with the appropriate filesystems. To do this, click on the blue-colored Logical View option in the left window segment and the Create New Logical Volume button at the bottom of the window. In the new dialog box, enter the relevant data for the drive to be integrated. While doing so, note that only ext2/3/4 and XFS filesystems are eligible.

If you check the Mount when rebooted option and specify a mount point, the system mounts the corresponding drive transparently in the existing directory tree after rebooting, allowing you to use it as a conventional subdirectory (Figure 4).

If you subsequently want to modify a logical drive, choose it in the Logical View at left, and click the Edit Properties button after you have enabled the volume in question. Next, configure the desired settings in the same dialog box you used to create the volume.

If you want to grab a snapshot of a logical volume to back up the filesystem, choose the Create Snapshot button. Clicking on it calls up a separate settings window, which provides various options for the snapshot. If necessary, you mount the snapshot as an ordinary directory in the filesystem.

Shrinking and Removing

Logical volumes in LVM installations can also be shrunk on the fly, which, among other things, lets you remove volumes from the storage pool. To remove a logical volume from the group, you only need to click it in the left pane and then select the Remove Selected Logical Volume(s) button. The software deletes the device from the group after a security prompt.

This option will not work if the volume already has a snapshot. To delete volume snapshots or snapshots themselves from the group, you need to select both components and then remove both together after the respective safety prompt.

To delete a physical volume from a LVM system, click on the corresponding Physical View on the left side of the application window and click on Remove Selected Physical Volume(s) to delete it from the system. This option proves to be especially useful when replacing mass storage media in a server system or cluster.

blivet-gui

As of Fedora 25, blivet-gui [5] replaces the previously used LVM as the default program for managing LVM installations. Earlier versions of blivet-gui are available in the repositories for the older versions of Fedora. The software is available from a separate PPA [5] for Ubuntu and its derivatives. Blivet-gui requires the Python blivet module, which uses Anaconda, the default installer on Fedora and Red Hat. The tool is visually based on GParted [6]. The functions are also similar to those of GParted: Before blivet-gui makes changes to the mass storage system, it collects them in a queue and then presents them to you for the OK to go ahead.

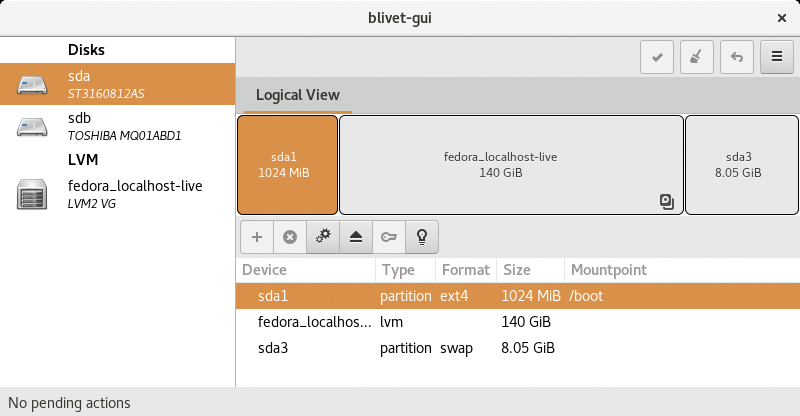

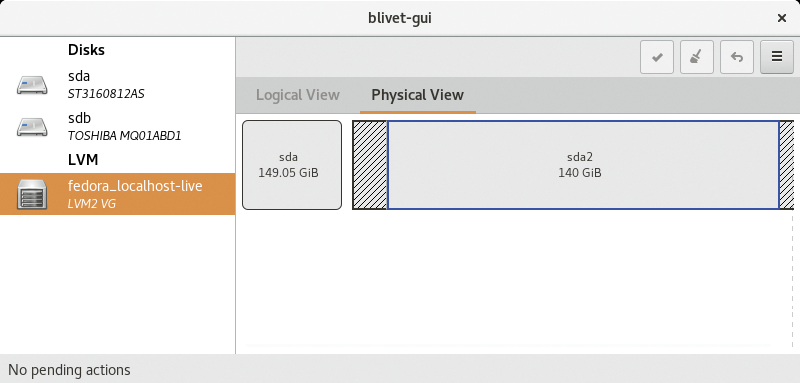

After a successful installation, a launcher can be found in the System submenu. As with LVM GUI, you call blivet-gui with administrator rights; after a short system scan, you are taken to a three-part interface (Figure 5).

Unlike its role model GParted, blivet-gui does not provide a menubar. You can control the program completely with the buttons at the top right in the program window and in the appropriate right-click context menus.

Interface

The left window segment shows a vertical list view of the physical and logical volumes in the system. The logical volumes are under Disks, and the block devices fall under LVM. The program window visualizes volumes as a horizontal bar, depending on the view selected on the left. Blivet users can switch the respective view using the Logical View and Physical View tabs (Figure 6).

Below the horizontal bar under Logical View, the individual volumes, including their relevant information, are arranged in a table; the view also includes the filesystem. Unlike LVM GUI, the number and size of physical extents are not shown here. If you switch over to the Physical View, no information appears below the bar display. This form of the view is particularly useful for a quick overview of logical volumes spanning multiple physical volumes in the system.

Actions

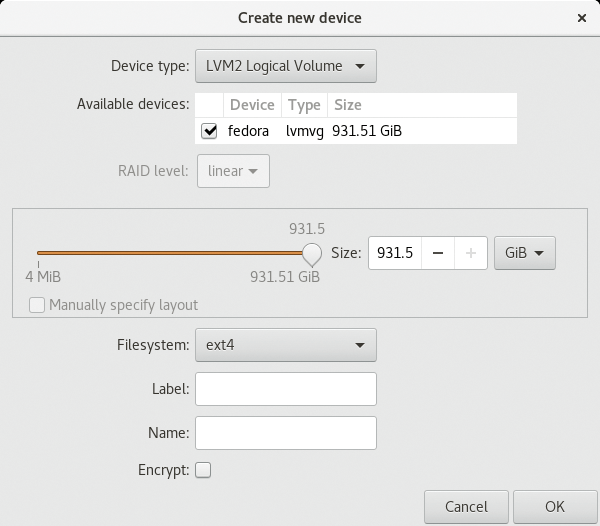

The blivet user performs individual configuration steps through context menus by right-clicking on a volume in the table view below the bar display. For example, you can select a physical volume that belongs to a volume group, but is still missing a logical volume, and set it up with a filesystem by clicking on New in the context menu.

Blivet-gui partly supports other filesystems that LVM GUI does not, including, for example, ReiserFS, which is no longer under development, and GFS2 [7], designed primarily for large clusters under Linux. With the slide control, you can set the size of the logical volume, or you can enter a value directly. Clicking OK integrates the new logical drive and makes it ready for operation (Figure 7).

To modify existing logical volumes, select Edit | Format from the context menu of the corresponding volume. You can delete a volume with Delete. The changes do not go into effect until you confirm them.

For this purpose, clicking the small button with a check mark at top right in the program window displays the pending operations in a separate window, but blivet only performs these actions after you press OK.

If you subsequently add new physical volumes to the system, you can first integrate them with an existing logical volume by selecting Edit | Modify parents in the context menu. You can adjust the size of the entire volume with Edit | Resize. To perform the jobs placed in a queue, click the Apply icon at top right to reconfigure the system.

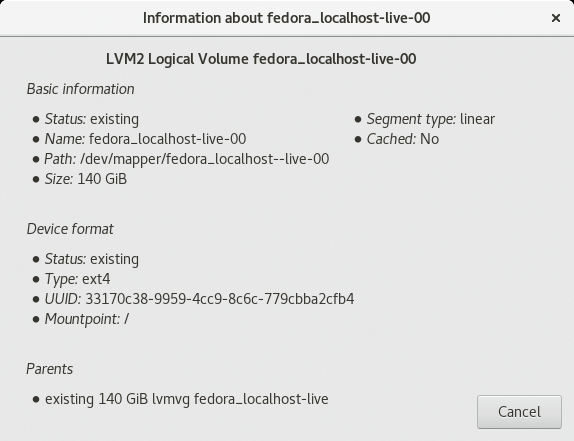

The Details

Unlike LVM GUI, blivet-gui reveals relatively few details about the devices and volumes. Although you can access some basic data in the Information menu item in the respective volume context menu, it does not include the number and size of the physical extents. However, blivet users can view this information and the underlying block devices and storage utilization by clicking on the respective volume group below the Disks header in the left window pane and then clicking on the light bulb icon directly below the bar graph (Figure 8).

GParted

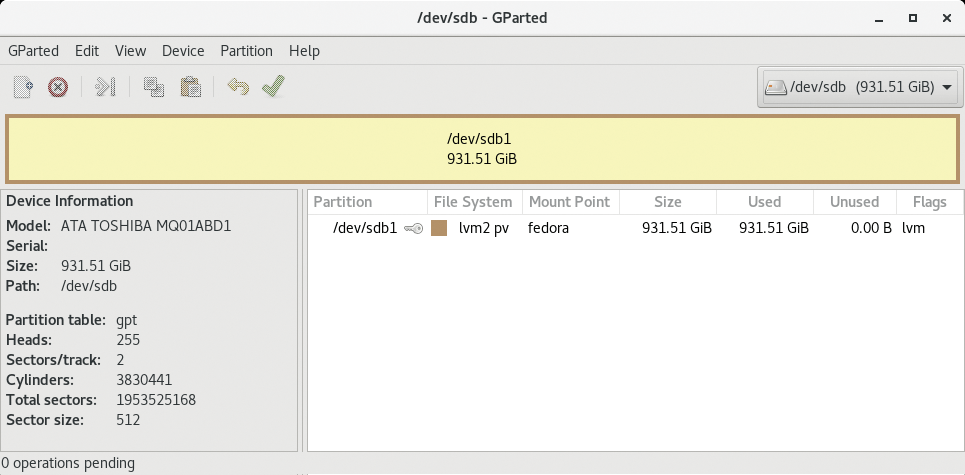

GParted, a graphical interface for the free GNU Parted partitioning tool, which is available from the repositories of most Linux distributions, has supported LVM volume groups since version 0.14.0. It relies on a four-part user interface: A buttonbar for speed dialing some functions is found below a horizontal menu line. A horizontal bar that appears underneath visualizes the current volume and its structure.

Data for the respective volumes and partitions appear in a tabular list at the bottom. A selection box at top right in the program window next to the buttonbar lets you select the physical devices in the system. Depending on the selected information, the table display can be split at the bottom of the window to view detailed information about individual volumes (Figure 9).

Even GParted does not perform the previously selected functions straightaway, but queues them first. You need to initiate the process explicitly to minimize the risk of accidentally deleting a whole disk because of a misguided choice.

Tools

GParted only partially implements support for LVM drives. Although you can create physical drives tagged as LVM on block devices, you cannot create volume groups and thus cannot define any mount points. Filesystems cannot be created on existing logical drives.

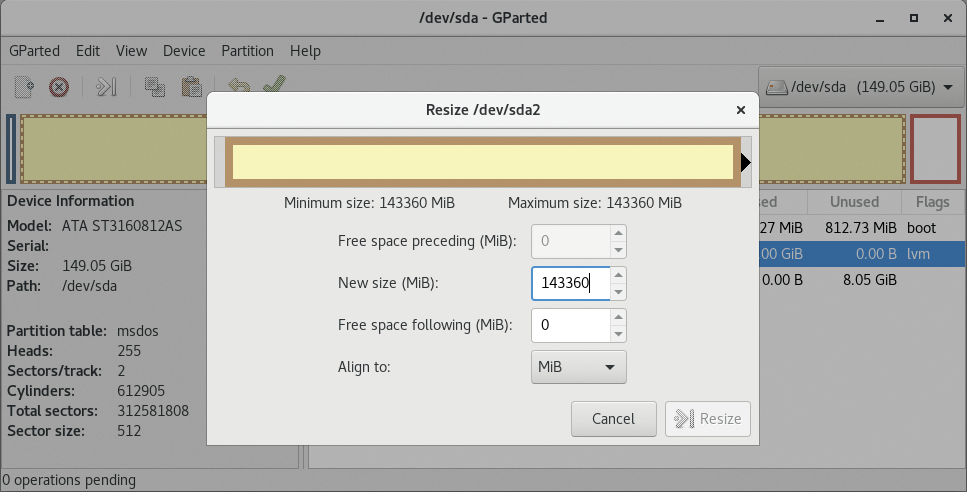

The main benefit of GParted, if you use an LVM system, is to grow (assuming you have enough free space on the block device) and shrink existing physical volumes without having to dismount the individual physical devices beforehand (Figure 10). To check devices, use the Check item in the context menu of the respective device.

GParted, including the latest Live version, is therefore only suitable to perform a subset of the tasks needed by a current LVM system.

YaST

YaST (Yet another Setup Tool) [8] has served openSUSE and a wide variety of derivatives for more than 20 years as an installation and configuration tool. YaST presents a sophisticated approach to creating and managing LVM systems. In doing so, it provides for most of the advantages that an LVM system offers, especially with regard to data protection.

Consider, however, that out of the box in current versions, openSUSE uses Btrfs [9] for the LVM root environment and XFS for the /home directory, which makes subsequent changes more complicated than with an ext4 filesystem. However, ext4 can be set as the default filesystem in the installation dialog of the operating system when you configure the LVM group.

To begin, open the YaST Control Center window from the start menu with System | YaST. In the System program group of the Control Center, you will find a Partitioner entry, which brings up a clear-cut Expert Partitioner window (Figure 11). The System View in the left pane is arranged vertically in a tree structure, where it also lists temporary devices. If you click on one of the entries in the System View, further context-sensitive information about the individual drives and partitions appears to the right. Below the information area on the right, YaST arranges several buttons specific to the selected view.

As part of Volume Management, the YaST module supports extensive configuration. YaST – like LVM GUI – does not distinguish between physical and logical volumes and displays all the devices in a table view in the right pane. Mount points and sizes also appear here, but not detailed information such as the size and number of physical extents or the selected drive's UUID.

You can view such details by clicking Edit below the table view. Doing so opens a display with three tabs – Overview, Logical Volumes, and Physical Volumes – and a horizontal bar arranged below that shows the utilization of the individual volumes.

Size Adjustment

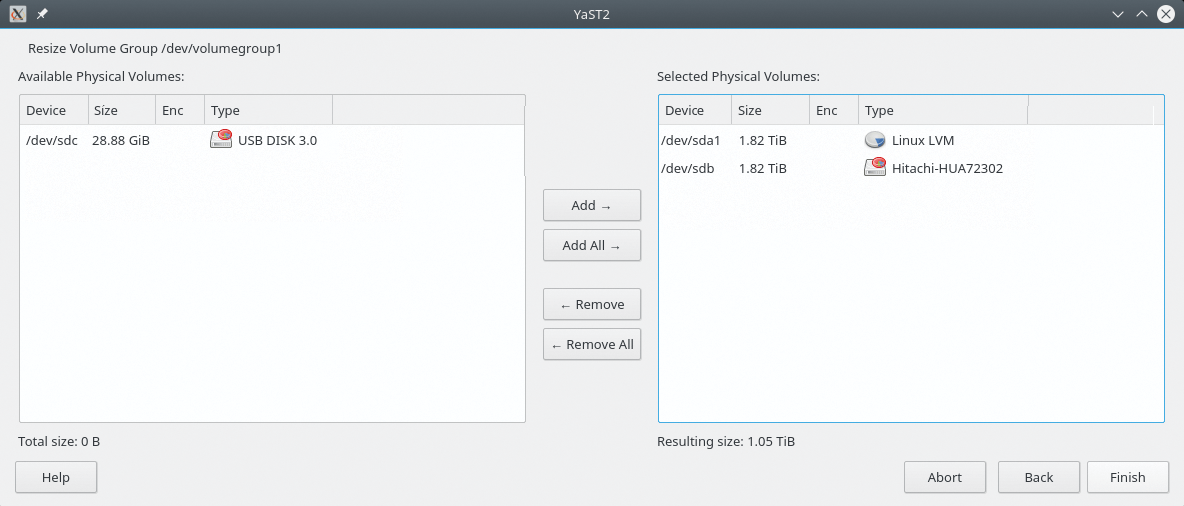

To change the size of a volume group, simply click on the Resize button. In the view that now opens (Figure 12), all the unallocated physical volumes appear with their size information in the left pane, and YaST lists the physical volumes with the corresponding volume groups to the right.

Clicking on one of the available physical volumes and then on the Add button between the two tables lets you move the available volume from the left view to the right view. You can then add it to the active LVM group with a single click on Finish. The display jumps back to the management view and adjusts the size of the volumes accordingly.

Next, you will probably want to allocate the newly available disk space to the logical volume. To do this, click on a logical volume in the active volume group, and then press the Resize button below the table view. In the dialog box, define the size of the volume or enter a capacity within the available space limits. Clicking OK immediately displays the change in the management display.

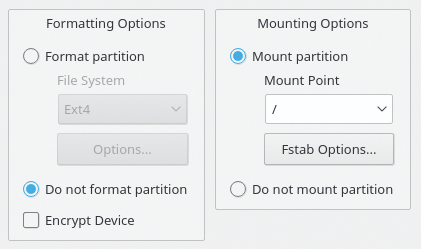

In a similarly convenient dialog, you can format existing drives and define mount points by clicking on the Edit button after choosing the desired logical volume. Two small dialog boxes open (Figure 13) in which you specify the filesystem to be created and the mount point of the logical volume.

/etc/fstab.Available filesystems include ext2/3/4, XFS, FAT, and Btrfs. Depending on the selected filesystem, additional parameters can be modified and an encryption algorithm applied. When specifying the mount point, you can manually edit the /etc/fstab file.

To create a new volume group or a logical volume, click Add in the volume manager. In the selection box that appears, decide whether to create a group or volume, and then configure all the necessary settings in a multiple-step dialog. In addition to the volume capacity and size of the physical extents, this includes defining the name of the volume, the filesystem to be used, and the options for mounting.

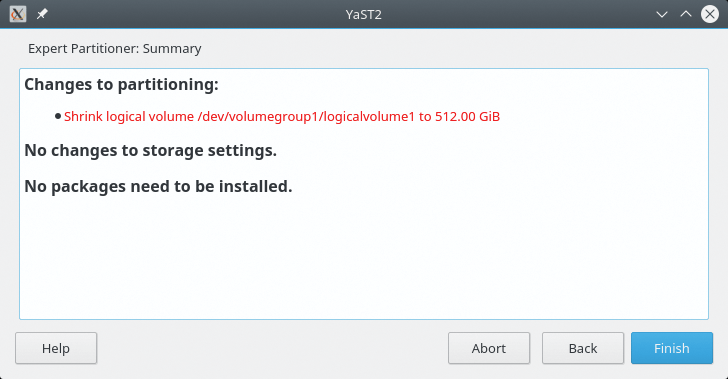

Before the software changes the system, YaST shows the steps required and only performs them after clicking on the Finish button. Thus, a last checkpoint allows you to intervene in the case of a faulty configuration (Figure 14).

Using the same approach, you can remove volume groups or logical volumes. To do so, choose the Delete button at bottom right in the manager. If the component to be removed is a mounted logical volume, an explicit warning appears stating that YaST will only let you delete after confirmation. This prevents data loss from operator error.

KVPM

The KDE Volume and Partition Manager (KVPM) [10], released under the GPLv3, was originally designed for KDE4; however, it then entered the repositories of Debian, Ubuntu, and Slackware, so it can be installed easily in the current Plasma 5 variants at the push of a button. Also on the project site is source code for installation on other distributions, along with a guide.

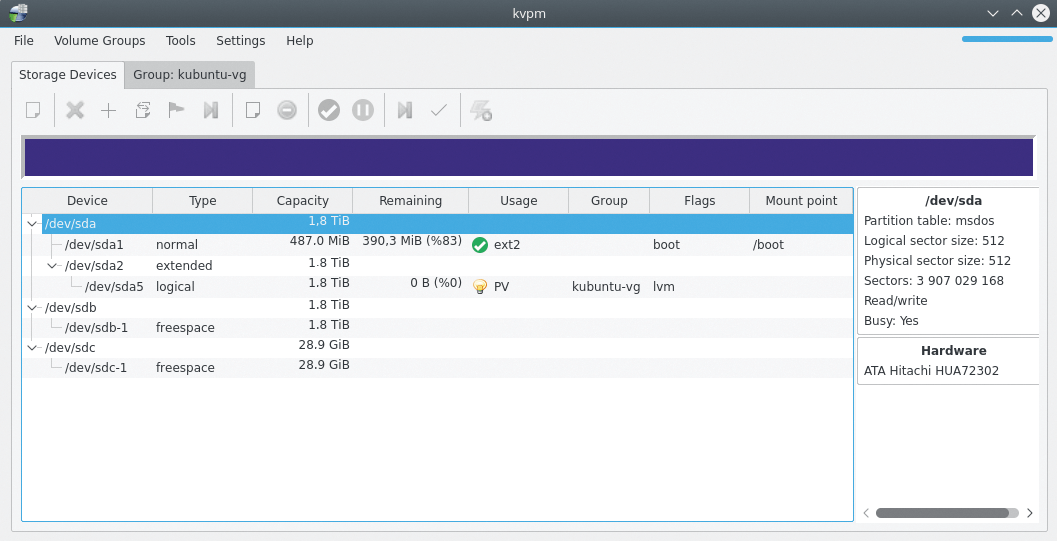

KVPM presents a rather confusing interface after launching LVM Volume And Partition Manager from the System menu (Figure 15). The main area, which lists volumes and partitions in tabular form, comprises two or more windows hidden behind tabs. Storage Devices lists the physical volumes and partitions, their types and utilization, as well as the mount points and flags. Depending on the configuration, additional tabs may exist, each containing information about a volume group.

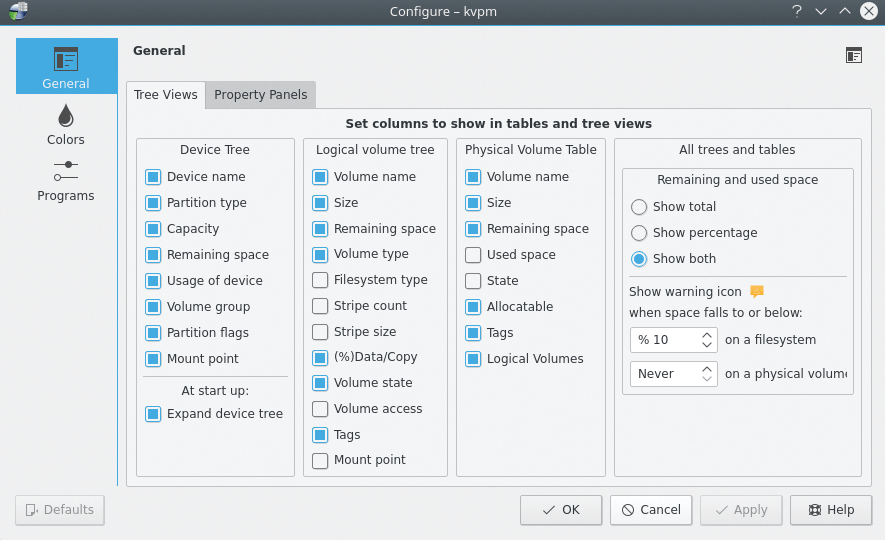

KVPM is one the few LVM tools to provide an extensive Settings menu. In the menubar across the top of the program window, the Settings menu allows you to configure some general settings for the components displayed in the current window, such as Configure kvpm to modify the tabular list of volume groups and logical drives to view or hide information (Figure 16).

Actions

KVPM provides both traditional menus and buttonbars for easy selection of individual functions. Context-sensitive buttons above the tables in color enable only those features that make sense in the respective tabs. Grayed-out buttons indicate functions you cannot use in the current context.

A third operator element comprises shortcut menus accessed by right-clicking a component in a table. The context menu options allow the same actions as the buttonbars and menubars, but they can be selected more quickly.

To create a new volume group, for example, right-click on the desired block device in the Storage Devices tab and select Create volume group. You need to remove old partition schemes on the block devices beforehand; otherwise, creating a volume group will fail. After deleting old partitions with the Create or remove a partition table item, you can generate new volume groups. Another tab shows the corresponding details.

Clicking in the menu generates a new logical volume in the volume group tab that can extend over multiple physical devices; you can specify names and sizes in the dialog box. Next, choose a filesystem for the new logical volume. Right-click to select Filesystem operations | Make or remove filesystem. Enable one of the supported filesystems in the dialog that appears: KVPM offers a large number of filesystems from which to choose. However, ext4 is the default; general options for ext filesystems, and specifically for ext4, appear in two additional tabs. After selecting a filesystem, mount it via Filesystem operations | Mount filesystem.

Group Dynamics

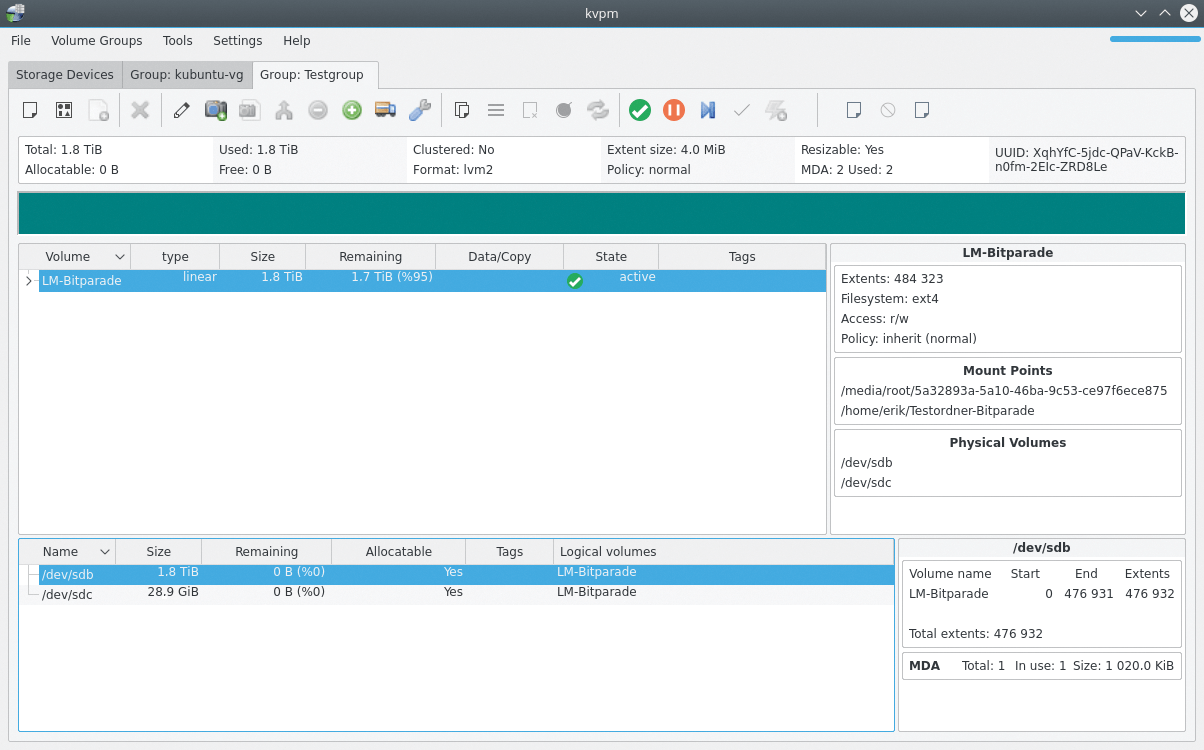

The Groups register not only shows detailed information about each volume group but offers features for managing logical volumes within a group. You can access most functions in a context-sensitive way using the horizontal buttonbar or by right-clicking on the desired volume in the table view (Figure 17).

You can shrink, grow, or rename volumes using the corresponding menu entries. You can also create snapshots at this point. Another option lets you split or merge volume groups from the Volume Groups menu. The menus also provide an option for deleting and creating new groups and logical drives, as well as for filling empty space.

KVPM makes it possible to manage LVM systems with virtually no compromises in terms of functionality compared with using the command line.

Conclusions

All of the tools I presented substantially facilitate the handling of LVM volume groups in clear-cut environments. Except for GParted, the tools demonstrate only small differences in functionality (see Table 1). Although GParted is suitable for growing, shrinking, and moving drives, it does not create new volumes and does not let you retrofit additional mass storage.

Tabelle 1: Graphical LVM Management Tools*

|

Feature |

LVM GUI |

blivet-gui |

GParted |

YaST |

KVPM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Create PVs |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Enlarge PVs |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Create PVs |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Create VGs |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Create VGs |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Enlarge VGs |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Reduce VGs |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Enlarge LVs |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Decrease LVs |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Specify the Size of the PE |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Delete LVs |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Delete VGs |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Decrease LVs |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Create Mirrored/Striped LVs |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Merge PVs |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Generate Snapshots |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Selectable Filesystems |

ext2/3/4 |

ext2/3/4, GFS2, FS-Reiser, Btrfs, XFS |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Packages |

RPM, DEB, Arch |

RPM, DEB#, Arch |

RPM, DEB, Arch, TXZ |

RPM# |

RPM, DEB, Arch, TXZ |

|

* LVs, logical volumes; PE, physical extents; PVs, physical volumes; VGs, volume groups. |

|||||

|

# DEB has its own Ubuntu PPA; RPM package is only available for openSUSE. |

KVPM provides a very solid functional scope with a clear operating concept but suffers from poor maintenance: The administrators of current Linux distributions need strong nerves to compile the program from source because of the many dependencies. In the test for this article, KVPM proved to be quite unstable under Ubuntu.

Blivet-gui and LVM GUI, on the other hand, adapt very well to existing LVM installations and prove to be very versatile, with both programs largely covering day-to-day tasks. YaST also manages LVM systems with attention to detail, but is limited to openSUSE and its derivatives.

In any case, you will want to opt for one of these tools if you continuously work with LVM. Because these tools support different filesystems, changing the tool could cause problems.